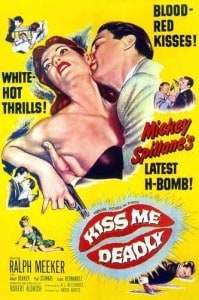

Blood red kisses! White hot thrills! Mickey Spillane’s latest H-bomb!

If you’re watching Kiss Me, Deadly for the first time, it will not be what you think. Sure, it’s one of the earliest of the Mike Hammer movies, the first being I, the Jury with Biff Elliot as Mickey Spillane’s hard-nosed private eye, and, true, there’s enough skulking, falling down stairs, muggings, knifings and killings to satisfy any modern detective aficionado. But the film, whose hard film noir look belies its three-week shooting schedule, becomes quite something else by the time of the climax—in fact, its plot, last minute like, has turned an unexpected corner.

Yes, this particular private eye film is something more . . . no, not “more” . . . something else. Something far more terrifying—and most portentous of things to come, what most sensible people, many of them properly frightened, were worrying about in the mid-’50s when Kiss Me, Deadly was made. Some lines toward the end where the film veers off course a little and first hints that it is, after all, a mutation, an aberration, a cross-fertilization of film genres:

“They’re harmless words,” says police Lieutenant Pat Murphy (Wesley Addy) to Hammer (Ralph Meeker). “Just a bunch of letters scrambled together. But their meaning is very important. Try to understand what they mean: ‘Manhattan Project.’ ‘Los Alamos.’ ‘Trinity.’ ”

Throughout the film, Hammer, this Los Angeles private dick so out for himself and such a user of others, has failed to heed his friend’s warnings, for he wants something out of it, whatever “it” is—and it must be something big if the FBI is involved. Even then, when the damage has been done and it’s too late, Murphy’s parting words, same scene, don’t sunk in: “What’s likely to happen to [your girl]? . . . Do you think you’d have done any different if you had known?”

In Mike’s case, certainly not.

Contradicting his sleek suits, array of sports cars and high class apartment, this guy, this Mike Hammer, is really a cruel, mechanical being, emotionally empty inside—empty of any real love for his women, compassion toward humanity in general or a sense of fair play among either friends or enemies. What’s it matter? Friends, enemies—they’re the same. When his lover says, “I’m always glad when you’re in trouble, ’cause then you come to me,” it’s clearly an overestimate of the man’s generosity and empathy. Hammer brutally, if that’s a strong enough word, assails a man who is following him, sending him rolling down a flight of concrete stairs, and with smiling delight crunches a man’s (Percy Helton) hand in a desk drawer to solicit information.

Contradicting his sleek suits, array of sports cars and high class apartment, this guy, this Mike Hammer, is really a cruel, mechanical being, emotionally empty inside—empty of any real love for his women, compassion toward humanity in general or a sense of fair play among either friends or enemies. What’s it matter? Friends, enemies—they’re the same. When his lover says, “I’m always glad when you’re in trouble, ’cause then you come to me,” it’s clearly an overestimate of the man’s generosity and empathy. Hammer brutally, if that’s a strong enough word, assails a man who is following him, sending him rolling down a flight of concrete stairs, and with smiling delight crunches a man’s (Percy Helton) hand in a desk drawer to solicit information.