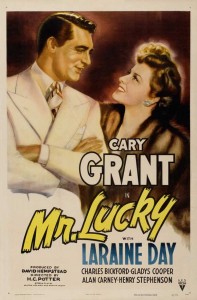

Cary at his grandest in the story he chose himself— plus lovely Laraine Day in the role that makes her great!

Around 1943, Cary Grant was trying to break out of the mold of the light comedian which had generally shaped his career up to that point—films like The Philadelphia Story, My Favorite Wife, Bringing Up Baby and Topper. There had been exceptions to this image. In Alfred Hitchcock’s Suspicion the script suggests he is planning to murder wife [intlink id=”288″ type=”category”]Joan Fontaine[/intlink], but the censors forced an about-face, and maybe even Grant wasn’t too enthusiastic about going that far. In Penny Serenade the drama is intensified, now in a well done soap opera about a couple’s legal fight in adopting a child.

For his so-called “breakout” role, the film Grant selected for 1943—there would be only one more that year—was Mr. Lucky. Because it appealed to him, Grant selected an original idea by Milton Holmes, who had no writing experience. The story, however, was formed into a screenplay by a number of writers, including legends Charles Brackett and Dudley Nichols. The results are delightful fun. “Delightful fun,” even considering this new, less-than-nice guy image—Grant now a crooked gambler? Hey, come on! This supposedly dreadful character doesn’t last for the entire hundred minutes of screen time. After all, this is Cary Grant!

The film is told in flashback by a ship captain, Swede (Charles Bickford, Major Terrill in The Big Country). He explains to a policeman why a classy gal is always visiting the wharf, how she will pace up and down, lean against a pier. Look out to sea. “She’s waiting for him,” Swede says. . . .

Seems, back when, a gambler, Joe Adams, owned a floating casino and had adopted the name of a dead man, Bascopolous, to obtain his “F” draft classification. (This being 1943, Mr. Lucky is a subtle support for the war.) In search of a place to establish a front for a backdoor gambling racket, Joe comes upon the American War Relief Society, run by women. Quite coincidentally, in the way of film and fiction, he bumps into Dorothy Bryant (lovely, starry-eyed Laraine Day), a society dish and volunteer at the organization.

After much persuasion and charm—impossible for Grant’s inimitable appeal not to emerge—Joe convinces an at first suspicious Dorothy that his offer is completely legitimate, that her ladies will receive their promised percentage of the take. He, of course, plans to double-cross her.

After much persuasion and charm—impossible for Grant’s inimitable appeal not to emerge—Joe convinces an at first suspicious Dorothy that his offer is completely legitimate, that her ladies will receive their promised percentage of the take. He, of course, plans to double-cross her.

Joe fascinates her with the rhyming slang he says he picked up in Australia. It’s similar to the Cockney slag long familiar to Grant from his earliest performing days in the London music halls. “Where’s my tit for tat?” he explains, means, “Where’s my hat?”

The light underlying tone of the film is emphasized in Grant’s scene with Florence Bates (the vulgar matron in Rebecca), who was cast frequently in the types of aggressive roles another Bates—Kathy (no relation)—would sometimes inhabit (Titanic, About Schmidt and, of course, Misery). Mrs. Every instructs Joe on how to knit, and his character takes to it assiduously, drawing the attention of a street crowd of men staring in at him through the store window.

Knitting becomes something of a recurring punch line in the film. When Dorothy first suggests that he take lessons from Mrs. Every, Joe repeats “knit?” about four times in staccato defiance. This alone is hilarious. When distracted, Joe says, “I dropped my purl.” After the gambler’s henchman, Crunk (Alan Carney, best remembered for his later TV work), has taken instruction on knitting, Joe warns him, “You dropped a stitch. Wait ’til I tell Mrs. Van Every.”

Knitting becomes something of a recurring punch line in the film. When Dorothy first suggests that he take lessons from Mrs. Every, Joe repeats “knit?” about four times in staccato defiance. This alone is hilarious. When distracted, Joe says, “I dropped my purl.” After the gambler’s henchman, Crunk (Alan Carney, best remembered for his later TV work), has taken instruction on knitting, Joe warns him, “You dropped a stitch. Wait ’til I tell Mrs. Van Every.”

Joe had planned to double-cross the ladies at their charity ball, but he hears a priest (Vladimir Sokoloff, Pop LeJon in Scarlet Street) read a letter from the real Joe Bascopolous’ mother, that the Nazis have killed all the men in her village. Joe suddenly acquires a patriotic fervor and decides to give the ladies their proper share. But another henchman, Zepp (Paul Stewart, the psychiatrist in Twelve O’Clock High), insists on the original plan. The War Relief is to receive a grand total of $812! Joe and Zepp shoot it out. Zepp is killed. Joe, wounded, leaves the ladies their rightful share of the take, wrapped in newspaper, and staggers off into the night. It’s rumored he sailed on the “Brimy Marlin,” destination unknown. Is he dead or alive?

And that’s why this girl, now known as a certain socialite Dorothy Bryant, is always pacing that wharf, peering out to sea: she’s waiting for a certain gambler, whom she loves and knows is now reformed, to return.

Lacking the glossy production values of M-G-M, or even Paramount, the cost-efficient RKO sometimes shows through. There are, however, some impressive visuals as, early in the film, a stevedore pulls back a large warehouse door—the height of the screen—revealing a cargo ship at the wharf—obviously a matte painting but still effective.

Lacking the glossy production values of M-G-M, or even Paramount, the cost-efficient RKO sometimes shows through. There are, however, some impressive visuals as, early in the film, a stevedore pulls back a large warehouse door—the height of the screen—revealing a cargo ship at the wharf—obviously a matte painting but still effective.

The cast features a number of familiar faces, including Henry Stephenson (Sir Macefield in The Charge of the Light Brigade) as Dorothy’s grandfather and Gladys Cooper (Bette Davis’ mother in Now, Voyager) and Mary Forbes (Lady Agatha in The Picture of Dorian Gray) as war relief volunteers. Walter Kingsford (Dr. Carew in the Dr. Kildare series) is Mr. Hargraves and J. M. Kerrigan (the slave-seller Gallegher in Gone with the Wind) is McDougal, one of the victims of Joe’s coin trick, which will feature in the film’s final scene.

From behind the camera, there are such well-knowns as H. C. Potter, the director who also guided Grant in Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House. Cinematographer George Barnes would serve Alfred Hitchcock in two of his early American films, Rebecca and Spellbound. And among the art directors is the justly famous William Cameron Menzies.

From behind the camera, there are such well-knowns as H. C. Potter, the director who also guided Grant in Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House. Cinematographer George Barnes would serve Alfred Hitchcock in two of his early American films, Rebecca and Spellbound. And among the art directors is the justly famous William Cameron Menzies.

Roy Webb, an unfairly neglected film composer, whose prodigious output is hardly embarrassing alongside Max Steiner’s, isn’t offered too many opportunities to shine. With his gift for light, romantic tunes, however, he works into his score Arthur Schwartz and Howard Dietz’ song “Something to Remember You By.” It’s most prominent at the charity ball, and Grant even whistles it on occasions.

Cary Grant had tried, with Mr. Lucky, to change his light, lady’s man persona. Did he succeed? Not really, perhaps. The charm, the wit, the graceful movement—there’re all still here. But his next film, the only other one he made in 1943, would be a World War II submarine adventure, Destination Tokyo. No ladies aboard there!