Here is a killer without conscience.

Here is a killer without conscience.

After such promise in his first film, as a violinist-turned-boxer in Golden Boy in 1939, William Holden’s career seemed headed nowhere, clearly not to the bigger and better things that that movie with Barbara Stanwyck had suggested. Despite a convincing performance in his third outing, Our Town (1940)—it passed unheralded and little attended—his next thirteen films largely alternated between dusty Westerns and light, nice-boy-next-door comedies.

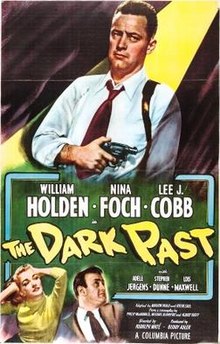

Then emerged, in 1948, The Dark Past, about an escaped murderer (Holden) who holds a family hostage. With Holden’s dual contracts at the time with both Columbia and Paramount, this effort came from Columbia, which had filmed the same story under the title Blind Alley in 1939 with Chester Morris in the criminal role.

A further use of the same plot would follow in The Desperate Hours (1955), now with Humphrey Bogart. The commandeered family home this time belongs to a department store executive (Fredric March); for Holden, the home owner is a psychiatrist.

And therein lies one of the problems for Holden, still a relatively inexperienced actor and clearly insecure in his profession. Lee J. Cobb, who had played Holden’s father in Golden Boy, was the psychiatrist, and the self-assured Cobb was not one to advise young actors in need of help. Besides, he grumbled constantly about the poor script and his dead-end role, maybe one reason his blustery acting, which had been so detrimental to Golden Boy, is much more restrained.

On the other hand, as in Golden Boy when Stanwyck took him under her wing, now in The Dark Past Nina Foch, playing his moll, invited Holden to come to the set early, shared her coffee and donuts—and gave professional advice. “In ten years,” she told Holden, “Cobb will still be a character actor. In ten years you’ll be a really big star.” That helped Holden immensely, reflected thereafter in the film. It’s probable that Billy Wilder watched the young actor and had kept him in mind. Holden is strong here, every bit the hardened killer.

On the other hand, as in Golden Boy when Stanwyck took him under her wing, now in The Dark Past Nina Foch, playing his moll, invited Holden to come to the set early, shared her coffee and donuts—and gave professional advice. “In ten years,” she told Holden, “Cobb will still be a character actor. In ten years you’ll be a really big star.” That helped Holden immensely, reflected thereafter in the film. It’s probable that Billy Wilder watched the young actor and had kept him in mind. Holden is strong here, every bit the hardened killer.

A police psychiatrist, Dr. Andrew Collins (Cobb), and his wife Ruth (Lois Maxwell) and son arrive at their country cabin. At the same time, murderer Al Walker (Holden) escapes from prison, killing his hostage, the warden, soon afterwar

d. He is accompanied by his girlfriend Betty (Foch) and two fellow escapees.

As in The Desperate Hours where Bogart, also with two henchmen, runs into complications, allowing March’s daughter a date with her boyfriend or arouse suspicion, so Walker finds that the Collins are entertaining three guests, who are promptly locked upstairs. The two servants are tied up in the basement.

Walker becomes belligerent when he catches Collins observing him, and the psychiatrist says it’s his job to observe people. When Betty informs Collins that Walker has been having nightmares, the psychiatrist tries to persuade him to confront them. Walker tells him to shut up, but Collins persists, indifferent to the death threats, explaining the eternal battle between the conscious and unconscious mind.

Collins eventually persuades Walker, despite repeated evasions, to describe his nightmare. He is in a rainstorm and cannot escape. When he tries to seal off a hole in the umbrella with his hand, the hand becomes paralyzed. The umbrella is surrounded by bars.

After Collins’ further prodding, Walker realizes that the umbrella is a table, the rain his father’s blood dripping through cracks in the top. He had reported his brutal father to the police, who had confronted him in a bar. In the ensuing gunfight, his father falls dead on the table, and the bars around the table are the legs of the police. Walker’s angst was guilt felt about his part in his father’s death.

In the meantime, the servants had freed themselves and alerted the police, who now surround Collins’ cabin. Unlike Bogart, who bolted out the front door into blazing spotlights and the suicidal gunfire of police, Walker surrenders meekly. (Unfortunately, The Desperate Hours would be remade in 1990 with Mickey Rourke in the Holden role and Anthony Hopkins as the home owner, all a ludicrous, overblown disaster.)

Five films after The Dark Past, after Holden had appeared in more Westerns and comedies, Wilder cast the actor as Joe Gillis in Sunset Boulevard. He received an Oscar nomination and three years later the statuette for another Wilder film, Stalag 17.

Five films after The Dark Past, after Holden had appeared in more Westerns and comedies, Wilder cast the actor as Joe Gillis in Sunset Boulevard. He received an Oscar nomination and three years later the statuette for another Wilder film, Stalag 17.

But the old ups and downs in film quality continued. Oh, sure, the movies were mostly “big” features—expensive, stellar co-stars, in color, longer, prestigious. But there would be the routine and the mediocre—The Moon Is Blue (1953), Alvarez Kelly (1966) and Open Season (1974)—and also the high points—The Country Girl (1954), The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), The Wild Bunch (1969) and Network (1976).

Tragically, William Holden was in an unintentional suicidal race with Errol Flynn to be John Barrymore’s successor as Hollywood’s booziest actor. After six films following Network—the titles best left unlisted—the actor, home alone, died during a drinking binge.