“It’s always difficult to keep personal prejudice out of a thing like this, and wherever you run into it, prejudice always obscures the truth.” – Juror No.8

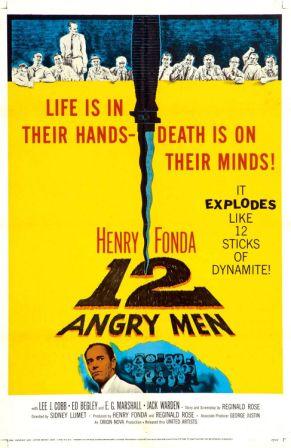

With the quite different standards of what constitutes a good, much less a great picture these days, 12 Angry Men isn’t the type of film that would attract many new viewers. First of all, most obviously, it’s in black and white, the usually preferred medium (over color) of critics but unnaturally abhorrent to average movie-goers. Also, the setting is primarily restricted to a single jury room, 16 x 24 feet. Dialogue is continuous and the film traverses its ninety-six minutes without violence, special effects or women.

Then there is the rather poor exterior backdrop outside the windows of practically the only set, the single, dreary jury room. It was initially criticized, and, true, that criticism remains valid. The film lost money on its theatrical release in 1957, mainly because of a poor distribution strategy, and with the passing of Jack Klugman in 2012, the nameless Juror No. 5, all the stars have died, as has the director, Sidney Lumet, in 2011.

But none of this matters. The film is a tight, compelling drama, excellently acted by a diverse cast of twelve, assuming the roles of twelve men of equally different temperament, intelligence, sophistication and work background. The film is used in business schools and presumably in a number of law colleges to teach cooperation methods and argument management.

In AFI’s top ten courtroom dramas, 12 Angry Men ranks second, after To Kill a Mockingbird (1963), though, technically, it’s a jury room drama, with no trial ever shown.

In AFI’s top ten courtroom dramas, 12 Angry Men ranks second, after To Kill a Mockingbird (1963), though, technically, it’s a jury room drama, with no trial ever shown.

From another courtroom drama on the list of ten, Anatomy of a Murder (1959), a quote by an alcoholic lawyer-friend (Arthur O’Connell) of James Stewart’s character illustrates the complexities, uncertainties and tensions of the jury process: “Twelve people go off into a room . . . And these twelve people are asked to judge another human being as different from them as they are from each other. And in their judgment, they must become of one mind, unanimous.”

That the 12 Angry Men jury is all white, all male, without any representation by blacks or women, let alone other nationalities (except one unspecified “European”), seems to have gone unmentioned in most reviews when the film first appeared. Male dominance was taken for granted; it was then, and is now to an unfortunate extent, part of the norm. These inequalities are important, but subjects for another article, under other circumstances.

Only two of the jurors’ names are revealed—and then not until the final scene. The twelve men represent a general cross-section of American life and most have ordinary, hard-working jobs. The most educated juror, No. 8 (Henry Fonda), with the most sophisticated occupation, is the one juror who feels, right from the first, that there must be deliberate and careful discussion, not a hasty rush to convict. An initial show of hands reveals that No. 8 is the only “not guilty” among the eleven votes of “guilty.”

Only two of the jurors’ names are revealed—and then not until the final scene. The twelve men represent a general cross-section of American life and most have ordinary, hard-working jobs. The most educated juror, No. 8 (Henry Fonda), with the most sophisticated occupation, is the one juror who feels, right from the first, that there must be deliberate and careful discussion, not a hasty rush to convict. An initial show of hands reveals that No. 8 is the only “not guilty” among the eleven votes of “guilty.”

Whether an acting deficiency overlooked by Lumet, who is making his theatrical film début, or a subtle jab at the sometimes indifferent, assembly-line approach to the justice system, the judge (Rudy Bond) apathetically charges the jury to render a verdict on an 18-year-old boy (John Savoca), who has stabbed his father to death. Any reasonable doubt, the judge admonishes, necessitates a “not guilty”; if unanimously found guilty, the sentence is automatically death.

The boy is from the slums and of an unspecified nationality, though he is obviously not a white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant, which gives Juror No. 10 an excuse to vent his racial prejudices.

Juror No. 1 (Martin Balsam), the even-tempered jury foreman, helps maintain order and quells some of the more volatile conduct which erupts among his companions.

At the single, long table in the room, each juror has his place, to which he returns after all the coffee and restroom breaks. To the foreman’s immediate left is a meek bank teller, Juror No. 2 (John Fiedler), shy and subservient to the others until, later, he becomes more outspoken.

A businessman, Juror No. 3 (Lee J. Cobb), is next, opinionated, easily angered and ready to argue any point that might dislodge his determined “guilty” vote—until the very end, that is. He is the last to change his vote.

A businessman, Juror No. 3 (Lee J. Cobb), is next, opinionated, easily angered and ready to argue any point that might dislodge his determined “guilty” vote—until the very end, that is. He is the last to change his vote.

A stock broker by trade, Juror No. 4 (E. G. Marshall) is a stickler for the facts, reflective of his analytical job as a stock broker. He is understandably one of the harder ones for Juror No. 8 to win over.

The first of two avid baseball fans in the room, Juror No. 5 (Klugman) grew up in the slums, so not only does he identify with the boy on trial—nameless as well—but he resents attacks on his own similar background, especially from Juror No. 10.

Juror No. 6 (Edward Binns) has, perhaps, a job just a bit lower than Juror No. 2’s bank position, that of house painter, but he has his principles and is eloquent in expressing them.

Juror No. 6 (Edward Binns) has, perhaps, a job just a bit lower than Juror No. 2’s bank position, that of house painter, but he has his principles and is eloquent in expressing them.

That other baseball enthusiast is so anxious to make a game, always looking at his watch, that he’s impatient for a final verdict so he can leave. A salesman, Juror No. 7 (Jack Warden) occupies the chair at the other end of the table, opposite the foreman.

The calming and guiding voice in the room is Juror No. 8 (Fonda), an architect.

The oldest man on the jury and the second to change his vote to “not guilty,” Juror No. 9 (Joseph Sweeney) is the one retiree in the group. Endowed with the experience of age, he is intelligent and perceptive.

Juror No. 10 (Ed Begley), a garage owner, is easily the most verbally bigoted of the twelve men, rivaling No. 3 as a blustering big-mouth.

A European watchmaker and now an American citizen, No. 11 (George Voskovec) is courteous and intent on using proper English.

Having gone clockwise around the table, to the foreman’s immediate right is Juror No. 12 (Robert Webber). An advertising director, he is easy with the wisecracks, the only juror to change his vote more than once during the numerous secret ballots.

Having gone clockwise around the table, to the foreman’s immediate right is Juror No. 12 (Robert Webber). An advertising director, he is easy with the wisecracks, the only juror to change his vote more than once during the numerous secret ballots.

Through debate, analysis and some strident arguments, Juror No. 8 proceeds to change the eleven men’s minds, and by the end of the film the men have rendered their unanimous “not guilty” verdict. As they leave the courthouse, Juror No. 9 asks No. 8 his name. “Davis,” he replies and No. 9 introduces himself as McCardle.

Presumably accomplished during a flashback/camera dolly along the jury table immediately after the men leave the room, otherwise there’s no indication that the jury ever entered the courtroom to deliver their verdict. Also, it’s certain that the jurors would not have been allowed the newspaper—already on the table when they entered!—or the knife that Juror No. 8 produced in his persuasions for “not guilty.”

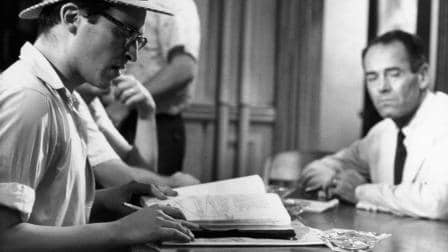

12 Angry Men was on a tight budget, to say the least, as shown by that unsatisfactory backdrop, and Lumet had to economize whenever he could. All the shots requiring the same lighting and camera setup were filmed at the same time, so in a two-way conversation, the response from the second actor, requiring another set-up, might have been filmed at entirely another time.

The director rehearsed his cast for two weeks, perhaps not only out of habit, having come from live television, but also to save time and avoid unnecessary retakes—and to save money. To instill the claustrophobic experience of jury room confinement, he kept his actors cloistered on that one set for hours on end.

The director rehearsed his cast for two weeks, perhaps not only out of habit, having come from live television, but also to save time and avoid unnecessary retakes—and to save money. To instill the claustrophobic experience of jury room confinement, he kept his actors cloistered on that one set for hours on end.

Using a psychological trick, Lumet began the film with above-eye-level shots—and overhead shots inside the jury room—and as the film progressed, he gradually lowered the camera until, by the end, it was below eye level, with ever-increasing close-ups. As the jurors are descending the stairs of the courtroom, the widest possible lens illustrates the freedom from the confining jury room the men must have felt.

Come Oscar time, 12 Angry Men received three nominations: for Best Picture, Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay by Reginald Rose. The film lost, in all three categories, to The Bridge on the River Kwai.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2L4IhbF2WK0[/embedyt]