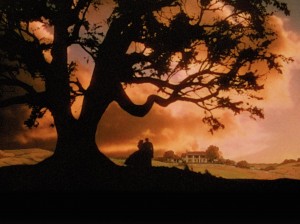

There was a land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields called the Old South.

Before now, Gone with the Wind has had at least five major theatrical re-releases, including the infamous 70mm sacrilege and the distorted, cropped 1967 “wide-screen” version, and there was, in 1998, that major restoration which was presumed to be—by most people except the technicians who profit from perennial restorations—realized perfection, for ever and a day. Finis.

[Here we are just talking about the new DVD releases. For a more detailed discussion of the film itself, please see our separate review at Seventy Years of Gone with the Wind.]

Hardly. GWTW is back, now more magnificently restored than ever. The standard format features the film only. More dramatic visual improvements will stun the eyes on the new Ultimate Collectors Edition releases for both standard DVD and the film’s first-ever bluray release, part of Warner Bros.’ 5-disc set with new and old features and documentaries, a replica of the original 1939 souvenir program, 40-page Production History Book, eight 5×7 prints and on and on, even a bonus CD with eight tracks of Max Steiner’s score.

Wow! It has to be seen to be believed, paid for to be received.

Seriously, the most intelligent and interesting extra is the two-hour The Making of a Legend: Gone with the Wind, a 1989 documentary by producer David O. Selznick’s sons, previously part of a GWTW DVD in 2004. It includes some of the numerous screen tests, especially for the roles of Scarlett O’Hara and Ashley Wilkes, with comments by actresses Ann Rutherford, Evelyn Keyes and Butterfly McQueen and Selznick representative Katherine Brown. All except Rutherford, who is 89, have since died, Keyes as recently as 2008.

The most glaring negative in these sets—and that it’s a major part of the 70th anniversary celebration makes it doubly unfortunate—is Rudy Behlmer’s commentary, regurgitated without further digestion from the 1998 DVD restoration. Then as now, and as in most of his other commentaries, Behlmer seems to be reading his text in another room; the turning pages almost crinkle. A similar ineptitude afflicts his commentary on 20,000 Leagues under the Sea and interview with its director Richard Fleischer. Although sometimes a bit impassive, Fleischer nonetheless must have been stunned by the inane, simplistic questions he was asked.

The most glaring negative in these sets—and that it’s a major part of the 70th anniversary celebration makes it doubly unfortunate—is Rudy Behlmer’s commentary, regurgitated without further digestion from the 1998 DVD restoration. Then as now, and as in most of his other commentaries, Behlmer seems to be reading his text in another room; the turning pages almost crinkle. A similar ineptitude afflicts his commentary on 20,000 Leagues under the Sea and interview with its director Richard Fleischer. Although sometimes a bit impassive, Fleischer nonetheless must have been stunned by the inane, simplistic questions he was asked.

For GWTW, Behlmer gives inconsequential information, say, the dates of the second, third and fourth rewrites of a script, or relates what’s on the screen . . . well, da-a-a-a—, haven’t we eyes! . . . or just when things become dramatic or there’s some dazzling photography, Behlmer turns his page and reviews stars’ careers, which is the gist of most of the second disc. While the Atlanta citizenry grieves over the casualty lists, Behlmer unemotionally drones, “Let me take just a moment here to talk about director Victor Fleming——” While Scarlett shoots the Union deserter on the staircase and Melanie removes her dressing gown to absorb the blood, Behlmer turns calmly to discussing Olivia de Havilland.

Perhaps too much space devoted to a negative, however serious it may be.

Nothing, though, can dim the magic and the nostalgia of Gone with the Wind. It is, after all, one of Hollywood’s most glorious milestones, grand storytelling at its best. What might excite the imagination is Behlmer’s list of the many filmed scenes that were cut from the first, second and possibly third edits—Scarlett consoling the dying John Wilkes, Belle Watling and her girls assisting at the hospital, the inquest about Frank Kennedy’s death, among others. What happened to these deleted scenes? Did Selznick destroy them? Are they stashed away, possibly lost, in some rusty reel tin? Intriguing.

If these scenes were found and were usable, could there be any justification for a truly complete version of GWTW—all five hours or so? Unthinkable, a heresy! Yes, the hypothesis may be intriguing, but such a change, though a gold mine for the restorers, would be a desecration—to Selznick’s final vision of the film, to the well-enshrined original and to the memories of many movie-goers who have loved it all through these seventy years.

In any event, SOME version of the film belongs in everyone’s collection and if you don’t have one already, this is a great time to make an addition. The extras (for the UCE) are deep – although not as pervasive as those for the recently released The Wizard of Oz. Warners continues to appear to be the only studio interested in mining older movies for bluray release for those of us interested in things less….modern.