“You’re not in London now, Doctor Garth, with your police. You’re in Transylvania in my castle.” — Countess Marya Zaleska (Gloria Holden) to Doctor Garth (Oscar Kruger)

Two British policemen, Hawkins (Halliwell Hobbes) and his subordinate Albert (Billy Bevan), creep cautiously down a flight of stone steps. On the floor lies a man with a broken neck. A meek looking, white-haired man (Edward Van Sloan as Professor Von Helsing) with wire-rim glasses emerges from the dark. He says he didn’t kill him, but the man who did lies . . . “in there.” While an anxious Albert remains behind, Hawkins investigates and finds a man in a coffin with a stake driven through his heart. The stranger admits to killing him, a certain Count Dracula.

“How long has he been dead?” Hawkins asks.

“About five hundred years,” the man replies.

And the dead man with the broken neck? The elderly man announces that it’s “a poor harmless imbecile who ate spiders and flies.” The two policemen exchange confused looks. (The death is never fully explained here, though Renfield was killed by Dracula five years earlier.)

In retrospect, at the end of Dracula (1931), set in the nineteenth century, Von Helsing (also played by Van Sloan) had killed Count Dracula with a stake through his heart, this at Carfax Castle outside London. Now, in Dracula’s Daughter, Von Helsing has just killed the count—it would seem again, but this is a somewhat confusing flashback to remind the audience what had happened at the end of the previous film, no mind that there’s been a big jump forward into the 1930s, with telephones and automobiles. Who cares. A peculiar time sequence, like logic, doesn’t matter in a horror film.

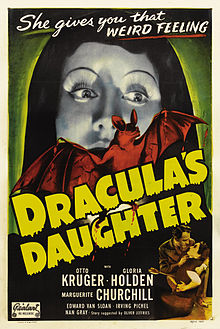

The conception and realization of Dracula’s Daughter endured more than the typical Hollywood problems. James Whale, director of Frankenstein (1931), The Invisible Man (1933), The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and a number of other horror masterpieces, had submitted a preposterous script that was immediately rejected. The final screenplay was based on both a chapter excised from the first publication of Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Sheridan Le Fanu’s short story Carmilla. When Bela Lugosi wanted too much money to reprise his role as Dracula, Universal hired writer John L. Balderston to, as Samuel Goldwyn would say, “include him out.” In the final film the count is absent, reaffirmed dead from the beginning.

The conception and realization of Dracula’s Daughter endured more than the typical Hollywood problems. James Whale, director of Frankenstein (1931), The Invisible Man (1933), The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and a number of other horror masterpieces, had submitted a preposterous script that was immediately rejected. The final screenplay was based on both a chapter excised from the first publication of Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Sheridan Le Fanu’s short story Carmilla. When Bela Lugosi wanted too much money to reprise his role as Dracula, Universal hired writer John L. Balderston to, as Samuel Goldwyn would say, “include him out.” In the final film the count is absent, reaffirmed dead from the beginning.

Among the rejected stars, Jane Wyatt was once considered; surely as the innocent girl Lili, since she’s hardly imaginable as the evil daughter. The return of Colin Clive and Boris Karloff, who had starred in Frankenstein, never materialized, and even Cesar Romero was scheduled to play the psychiatrist Von Helsing consults.

To further complicate things, the original director, A. Edward Sutherland, at the time a high-paid director and best known for W. C. Fields and Laurel and Hardy comedies, was too expensive to retain on the payroll and was replaced by the much cheaper Lambert Hillyer. A Western specialist who had made William S. Hart a star, Hillyer, it seems, fell victim of the film’s problems and was injured on the set soon after production began.

To further complicate things, the original director, A. Edward Sutherland, at the time a high-paid director and best known for W. C. Fields and Laurel and Hardy comedies, was too expensive to retain on the payroll and was replaced by the much cheaper Lambert Hillyer. A Western specialist who had made William S. Hart a star, Hillyer, it seems, fell victim of the film’s problems and was injured on the set soon after production began.

Despite the low-budget trappings of some of the sets—some borrowed from Dracula—Dracula’s Daughter was one of the most expensive Universal productions to date. When the studio’s principal debtor seized control, it would be the last film released under its head, Carl Laemmle, who had founded the company years earlier.

At Scotland Yard, the arrested Von Helsing endeavors to convince the commissioner, Sir Basil Humphrey (Gilbert Emery), that Count Dracula had died centuries ago, and that as a vampire he had existed on the blood of the living, turning them, in turn, into vampires.

Unable to convince Sir Humphrey, Von Helsing requests for his defense his psychiatrist friend, Dr. Jeffrey Garth (Otto Kruger). Garth’s “appointment,” as he said, “with several grouse” on a hunting party is interrupted when his secretary/cum girl Friday, Janet (Marguerite Churchill), comes to take him to Scotland Yard.

Unable to convince Sir Humphrey, Von Helsing requests for his defense his psychiatrist friend, Dr. Jeffrey Garth (Otto Kruger). Garth’s “appointment,” as he said, “with several grouse” on a hunting party is interrupted when his secretary/cum girl Friday, Janet (Marguerite Churchill), comes to take him to Scotland Yard.

While Garth finally agrees to work on Von Helsing’s behalf, Countess Marya Zaleska (Gloria Holden) and her manservant, Sandor (Irving Pichel), plan to steal Dracula’s body from the Whitby police station where it has been moved. She believes, by burning Dracula’s body, she can rid herself of her own curse of vampirism.

After a lengthy comic exchange between Hawkins and Albert about rats and noises from the room with the two corpses—Renfield is referred to only as “that other body”—Hawkins leaves Albert in charge while he departs for Scotland Yard to recruit a sergeant (E.E. Clive). As he leaves, Hawkins quotes Nelson’s great line before the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805: “England expects that every man will do his duty.” Zaleska arrives, hypnotizes Albert with reflections from her finger ring and steals the count’s body.

Having burned the body, and despite Sandor seeing only death in her eyes, Zaleska sits at the piano, telling him that, now, she can play happy music and live a normal life. She plays Chopin’s Nocturne No. 5 in F-Sharp, Op. 15, No. 2, calling it “the cradle song.”

Having burned the body, and despite Sandor seeing only death in her eyes, Zaleska sits at the piano, telling him that, now, she can play happy music and live a normal life. She plays Chopin’s Nocturne No. 5 in F-Sharp, Op. 15, No. 2, calling it “the cradle song.”

(Chopin’s cradle song is the Berceuse in D-Flat, Op. 57. It’s always amazing that, throughout the movies, these actors are able to “play” a piano—always dubbed by a professional—while carrying on a conversation. It’s even more ridiculous here, as the piece is technically challenging and Zaleska, realizing the curse still possesses her, becomes more stressed as she plays. Not only can she still play, but her performance is unchanged!)

Later, with Sandor’s help donning the trademark cloak of the vampire, well established by Lugosi in Dracula, she slides into the night and obtains her quota of blood from an apparent theatergoer innocently lighting a cigarette.

Then at a society gathering, Zaleska is asked by a Lady Hammond (Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper) if she would like some sherry. In reply, Zaleska quotes Dracula’s famous 1931 line, “Thank you, I never drink . . . wine.”

Then at a society gathering, Zaleska is asked by a Lady Hammond (Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper) if she would like some sherry. In reply, Zaleska quotes Dracula’s famous 1931 line, “Thank you, I never drink . . . wine.”

Since coincidences occur frequently in the movies, so, not surprisingly, Zaleska just happens to meet Dr. Garth at the same party. She immediately requests his counsel as a psychiatrist, to rid her of certain anxieties, though she avoids identifying her specific malady. And since borrowed quotes are frequent in Dracula’s Daughter, the lady paraphrases Hamlet when she tells Garth, “Possibly there are more things in heaven and Earth than are dreamed of in your psychiatry . . . ”

Meeting her at her apartment, the good doctor observes, “You know, this is the first woman’s flat I’ve been in that didn’t have at least twenty mirrors in it.” When she even reminds him that vampires don’t cast reflections in mirrors, its import seems to elude him. Zaleska then comes as close as she dare in stating her problem: “Someone, something, reaches out from the grave and fills me with horrible impulses.”

The countess tests Garth’s advice that she defeat her cravings by confronting them. While preparing to paint a model Sandor has acquired for her, Zaleska initially resists her temptations toward the young girl, Lili (Nan Grey). Then, compulsively, Zaleska asks Lili if she admires fine jewelry, and induces a trance with her shiny ring and then——

The countess tests Garth’s advice that she defeat her cravings by confronting them. While preparing to paint a model Sandor has acquired for her, Zaleska initially resists her temptations toward the young girl, Lili (Nan Grey). Then, compulsively, Zaleska asks Lili if she admires fine jewelry, and induces a trance with her shiny ring and then——

Doctors find the comatose Lili with two puncture marks on her neck. They are puzzled, but Garth understands and in his attempt to revive her, she dies from a heart attack.

Accepting that she must remain a vampire, Zaleska kidnaps Janet to lure Garth to her castle in Transylvania. In exchange for Janet’s life, Garth agrees to be transformed into a vampire, thus sharing eternal life with the countess. But Sandor shoots an arrow through Zaleska’s heart as revenge for her broken promise to make him immortal. When he tries to kill Garth, the arriving police kill him. Since thewooden arrow in Zaleska’s heart is a sufficient substitute for a stake, she dies—finally and forever.

Garth rushes to the sofa where Janet has been put into a trance by the countess. The arrow in Zaleska’s heart has released Janet, and seeing him, she lifts herself into his arms. “Oh, Jeffrey!” she says. But Von Helsing has the last word. When a policeman marvels that the dead woman is beautiful, he remarks, “She was beautiful when she died—a hundred years ago.”

Garth rushes to the sofa where Janet has been put into a trance by the countess. The arrow in Zaleska’s heart has released Janet, and seeing him, she lifts herself into his arms. “Oh, Jeffrey!” she says. But Von Helsing has the last word. When a policeman marvels that the dead woman is beautiful, he remarks, “She was beautiful when she died—a hundred years ago.”

Gloria Holden initially resisted appearing in a horror film in her first starring appearance, but it proved her most memorable role—chilling and stoic, beautiful but imperiously frightening. She would appear in “more respectable” films, The Life of Emile Zola (1937) and Random Harvest (1942), although in smaller parts.

Generally lost to television after 1948, Otto Kruger, always dependable, is quite convincing as the patient, earnest Dr. Garth. Tall and slender, with a narrow, angular face and abundant wavy hair, he projects a commanding presence. He would later appear in Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942), Murder, My Sweet (1944), with Dick Powell and Claire Trevor, in both as villains, and in High Noon (1952) as a fleeing lawyer fearing retribution from a returning gunslinger he had sent to prison.

On the one side are Kruger’s confrontations with Holden, reserved and professional, as suits a psychiatrist; he really never “comes on” to the lady. In another way, his scenes with Marguerite Churchill contain, by far, the closest approach to any real chemistry. It’s clear that the two characters have a rapport (and the actors a degree of charisma), comic and playful much of the time.

On the one side are Kruger’s confrontations with Holden, reserved and professional, as suits a psychiatrist; he really never “comes on” to the lady. In another way, his scenes with Marguerite Churchill contain, by far, the closest approach to any real chemistry. It’s clear that the two characters have a rapport (and the actors a degree of charisma), comic and playful much of the time.

In two separate scenes she ties his bow tie, since he’s all thumbs, first deliberately making it crooked. In a later scene she ties it properly. “Why didn’t you do it that way the first time?” he half angrily grumbles. When Churchill’s impersonation on the phone leads to Kruger’s embarrassment, he fires her. She hands him her resignation, but when, moments later, there’s an emergency and he says she must accompany him, she’s willing and able.

In an indefinable way, some viewers may see a slight resemblance between Churchill and Katharine Hepburn—in the wide-set eyes, the shape of the lips, a certain sparkle in the eyes, even in the sound of her voice, though Churchill is from the Midwest, Hepburn a proud New Englander. Even Churchill’s muted coquettish antics, her slightly tomboy teasing, recall Hepburn in her more animated moments.