“Badges? We ain’t got no badges. We don’t need no badges. I don’t have to show you any stinking badges.” — Gold Hat (Alfonso Bedoya) to the prospectors

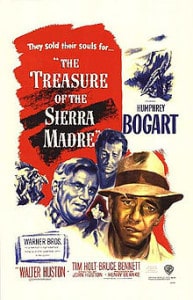

Unlike some of John Huston’s films that were done for the money, or as a relaxing diversion or to mark time until something better came along, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre was one of those special projects the director had long had in mind. Other similar passions include his first film for Warner Bros., the 1941 version of The Maltese Falcon, later Moby Dick and The Man Who Would Be King. Besides fulfilling his predilection for themes on hard-fought battles lost or the disillusion of life, in Treasure he foresaw a great role for his father, Walter, as the toothless, grizzled old prospector.

As so often with Huston, getting started on a film, or even surviving once started, was an ordeal in itself, even when he wasn’t imposing challenges and the nearly impossible on himself. As if, for example, the hostile location of darkest Africa wasn’t enough during The African Queen, he returned a few years later for The Roots of Heaven. “The location,” he wrote in his autobiography, An Open Book, “was one of the most difficult I have ever been on.” Worse than Queen? He knew Katharine Hepburn could vouch for that ordeal; she even wrote a book about it!

There were other similar situations. Desaturating and tinting the color, and otherwise giving the Moulin Rouge a monochromatic hue, prompted Technicolor officials to refute any responsibility for the outcome. For Moby Dick, there were no less than three accursed mechanical whales, one breaking its moorings and becoming a sea hazard; and, according to Huston, he almost lost his lead actor, Gregory Peck, during filming. And then there were the temperamental, mentally unstable and alcoholic stars whom Huston took on knowingly, almost as a challenge: Marilyn Monroe, Montgomery Clift and Errol Flynn. Huston, who knew Errol was dying from alcohol and drug abuse, wrote that he didn’t regret taking him along on The Roots of Heaven: “[Flynn] said afterward that he’d not had such a good time in years.”

The director, who could be a man of fathomless benevolence—he loved animals, adopted a Mexican orphan—was also a wicked practical joker. When he received his World War II assignment as a documentary film maker, he had almost finished Across the Pacific, about a Japanese plan to attack the Panama Canal—a reuniting of [intlink id=”189″ type=”category”]Humphrey Bogart[/intlink], Mary Astor and Sidney Greenstreet from The Maltese Falcon. In the last scene he directed before his departure, he filmed Bogart as a tied up prisoner, guarded by a throng of Japanese soldiers. It was up to his replacement director, Vincent Sherman, to figure how to extricate the hero.

The director, who could be a man of fathomless benevolence—he loved animals, adopted a Mexican orphan—was also a wicked practical joker. When he received his World War II assignment as a documentary film maker, he had almost finished Across the Pacific, about a Japanese plan to attack the Panama Canal—a reuniting of [intlink id=”189″ type=”category”]Humphrey Bogart[/intlink], Mary Astor and Sidney Greenstreet from The Maltese Falcon. In the last scene he directed before his departure, he filmed Bogart as a tied up prisoner, guarded by a throng of Japanese soldiers. It was up to his replacement director, Vincent Sherman, to figure how to extricate the hero.