“Confidentially, I think you’re a bit of a stinker, too.”— Michael Redgrave to Margaret Lockwood in the early part of the movie

“Confidentially, I think you’re a bit of a stinker, too.”— Michael Redgrave to Margaret Lockwood in the early part of the movie

Unlike John Huston who would frequently direct some light fare after a “heavy” picture, Alfred Hitchcock would often follow a dark film with an even darker one, and the over-all landscape of his oeuvre shows a gradual darkening, often meaning a growing explicitness. After all, did not The Birds follow Psycho? It would be hard, though, to know which is the more frightening—the menace in both is often unseen. And after two films of political intrigue, Torn Curtain and Topaz, both far below Hitch’s high standards, came his most sexually vulgar effort, Frenzy.

But, no, this thinking isn’t always correct. The reverse is just as often true. After a warning, in 1940, that World War II could spread to American shores in Foreign Correspondent, the director relaxed with Mr. and Mrs. Smith, his only romantic comedy. It was more as a favor to Carole Lombard than any urgent need of expression. Fifteen years later, after two fluffy films, To Catch a Thief and The Trouble with Harry, came the remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much, which, despite the advantages of VistaVision and Technicolor, many regard as inferior to the 1934 original.

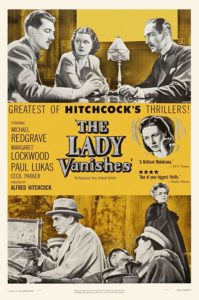

Though not totally unexpected—the previous movie, Young and Innocent, was also a comedy and a “journey” film—The Lady Vanishes remains a breed all its own, so light-hearted and, to a degree, so implausible in plot that it’s difficult to believe it ranks as one of Hitchcock’s masterpieces, but a masterpiece it is. François Truffaut, who conducted an extended interview with Hitch in 1962, later published in book form, considered The Lady Vanishes the most typical of all the director’s films.

As Truffaut said during the interview, “They show [The Lady Vanishes] very often in Paris. Sometimes I see it twice in one week. Since I know it by heart, I tell myself each time that I’m going to ignore the plot, to examine the train and see if it’s really moving, or to look at the transparencies, or to study the camera movements inside the compartments. But each time, I become so absorbed by the characters and the story that I’ve yet to figure out the mechanics of the film.”

As Truffaut said during the interview, “They show [The Lady Vanishes] very often in Paris. Sometimes I see it twice in one week. Since I know it by heart, I tell myself each time that I’m going to ignore the plot, to examine the train and see if it’s really moving, or to look at the transparencies, or to study the camera movements inside the compartments. But each time, I become so absorbed by the characters and the story that I’ve yet to figure out the mechanics of the film.”

The Lady Vanishes and The 39 Steps are the best known of Hitch’s pre-Hollywood sound films, nestled, as they are, among some darker works—Secret Agent, the original The Man Who Knew Too Much and perhaps the bleakest of the ’30s films, Sabotage. Coincidentally, The Lady Vanishes was followed by one of Hitch’s great failures, Jamaica Inn, his last film before leaving England for the greater opportunities and technical advantages of Hollywood.

His first film in Tinsel Town, despite the unwanted, and resented, meddling of David O. Selznick—and that Hitch himself never regarded it as a “Hitchcock picture”—was a smash hit, financially and critically, even beyond Selznick’s wildest dreams, and he always dreamed big. Rebecca earned Hitchcock the first of his five Oscar nominations, none earning a statuette. Two of the ten other nominations for Rebecca produced wins—for Best Picture of 1940 and George Barnes’ B&W cinematography.

The Lady Vanishes is based on Ethel Lina White’s novel The Wheel Spins. Hitch made a few changes, including the ending, and added a gunfight—and more humor.

The Lady Vanishes is based on Ethel Lina White’s novel The Wheel Spins. Hitch made a few changes, including the ending, and added a gunfight—and more humor.

After an avalanche has forced several groups of travelers to spend the night in a hotel in the Balkans where the guests either become friends or establish a few resentments, they board a train for London. Returning home to her fiancé after a vacation is a young English woman, Iris Henderson (Margaret Lockwood), who encounters a rude musicologist, Gilbert (Michael Redgrave), and a charming old governess and music teacher, Miss Froy (Dame May Whitty), whom Iris likes instantly.

When departing the train station, Iris had been struck on the head by a flowerpot pushed from a windowsill, seemingly intended for Miss Froy. Dr. Hartz ([intlink id=”31″ type=”category”]Paul Lukas[/intlink]) suggests that the blow has caused her to hallucinate, that the said Miss Froy, whom Iris insists has disappeared from the train, never existed. All the passengers deny ever seeing the lady—two cricket enthusiasts, Charters and Caldicott (Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne), a barrister (Cecil Parker) traveling with his mistress (Linden Travers), a black-attired baroness (Mary Clare), a nun (Catherine Lacey), a magician (Philip Leaver) and a few others.

Iris turning to Gilbert for help seems somehow natural in that typically Hitchcockian way and they gradually become more cordial. Gilbert at first doubts her about a disappearing old lady, but gradually little things support her—the nun who wears high heels; a strange patient, head wrapped in bandages, of the doctor’s; and Iris’ insistence that the missing woman had written “Froy” in the dust on a train window, though the letters unaccountably vanish before Gilbert can see them. Gilbert finally believes her when he sees a Harriman’s tea label plastered to a window pane when the cook throws out the kitchen garbage. That brand was the only tea Miss Froy would drink, and she had given a packet to the waiter.

Iris turning to Gilbert for help seems somehow natural in that typically Hitchcockian way and they gradually become more cordial. Gilbert at first doubts her about a disappearing old lady, but gradually little things support her—the nun who wears high heels; a strange patient, head wrapped in bandages, of the doctor’s; and Iris’ insistence that the missing woman had written “Froy” in the dust on a train window, though the letters unaccountably vanish before Gilbert can see them. Gilbert finally believes her when he sees a Harriman’s tea label plastered to a window pane when the cook throws out the kitchen garbage. That brand was the only tea Miss Froy would drink, and she had given a packet to the waiter.