“He was born with a gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad.” — opening line of Rafael Sabatini’s Scaramouche

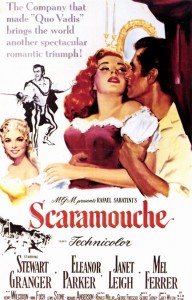

Scaramouche is out of place in film history. It clings tenaciously at the end of Hollywood’s Golden Age, declared by many critics to have ended a few years earlier. Peter Bogdanovich, on the other hand, rather generously, I think, contends that that era ended ten years later with The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, the last great film of John Ford. I for one would suggest 1962 is far too late: by then the deterioration was well underway. Scaramouche, based on the 1921 novel by the Rafael Sabatini of Captain Blood and The Sea Hawk fame, was as much of an anachronism in 1952 as Liberty Valance was in its day.

So why an anachronistic Scaramouche? The cast and the score aside, just the look of the film conveys the late ’30s, early ’40s, a favorable companion in spirit to The Scarlet Pimpernel, its rich, three-strip Technicolor worthy of The Adventures of Robin Hood. There’s a polished sheen to everything—a sleek plot, a witty script and smooth execution, all packaged in a way that recalls that other time. George Sidney’s direction is surprisingly tight for a swashbuckler; he was ignored by the Oscar folks during the thirty years of his career but received any number of other awards, including a nomination by the Directors Guild of America for Scaramouche. And the spectacular cinematography is by, perhaps not too familiar a name, Charles Rosher, who won two Oscars during his lifetime, including one for The Yearling.

Other well known production individuals include editor James E. Newcom, who edited a similar film, the 1937 version of The Prisoner of Zenda, and whose last film, to bring him more into perspective, was Tora! Tora! Tora! in 1970. He died twenty years later, having never been especially prolific. Art director Cedric Gibbons, assisted in Scaramouche by Hans Peters, has to his credit, among countless titles, Mrs. Miniver, Gaslight (1944) and An American in Paris. Dying at age forty-three, soon after his work on Scaramouche, costume designer Gile Steele was a co-nominee that same year for The Merry Widow.

Not to be forgotten, there is that considerable plus—Victor Young’s score, one moment flamboyant, the next lyrically romantic, one of his best, in the tradition of Erich Wolfgang Korngold, whose last original score was more than five years earlier. Young’s work deserves a discussion all its own, but, within these limitations, a little more later.

Not to be forgotten, there is that considerable plus—Victor Young’s score, one moment flamboyant, the next lyrically romantic, one of his best, in the tradition of Erich Wolfgang Korngold, whose last original score was more than five years earlier. Young’s work deserves a discussion all its own, but, within these limitations, a little more later.

And then the cast, which is headed by Stewart Granger, Eleanor Parker and Janet Leigh, recalls the glittering stars who could be assembled in the glory days. But let’s introduce the stars, including an admirable supporting cast, within the context of the story:

Appropriate for a swashbuckler set in revolutionary France, Scaramouche begins with dueling. Noel, Marquis de Maynes (Mel Ferrer), reputed to be the finest swordsman in France, is killing off Queen Marie Antoinette’s (Nina Foch) nobles with a rapidity that disturbs her. She warns Noel that the aristocracy must stick together in these times of revolution and suggests he marry to preserve his noble name. She introduces him to Aline de Gavrillac (Leigh, whose wide-eyed, modern face seems out of place in a late eighteenth-century French setting).

Appropriate for a swashbuckler set in revolutionary France, Scaramouche begins with dueling. Noel, Marquis de Maynes (Mel Ferrer), reputed to be the finest swordsman in France, is killing off Queen Marie Antoinette’s (Nina Foch) nobles with a rapidity that disturbs her. She warns Noel that the aristocracy must stick together in these times of revolution and suggests he marry to preserve his noble name. She introduces him to Aline de Gavrillac (Leigh, whose wide-eyed, modern face seems out of place in a late eighteenth-century French setting).

In another part of the woods—literally in the forest camp of the theatrical troupe of Gaston Binet (Robert Coote)—the carefree libertine André Moreau (Granger) arrives in search of his lover Lenore (Parker), who has gone to Paris to marry a rich sausage merchant (Howard Freeman). André intercepts the couple’s hansom en route to the church, kisses her passionately and proposes marriage himself. Here André says for the first time the line that he will repeat often to pacify his women: “Don’t be nervous.”

Leaving Lenore with the promise of procuring the ring, André arrives at the home of a couple he has treated like his own parents. (Lewis Stone, the husband, played Marquis de Maynes in the 1923 silent version of Scaramouche, with Ramon Novarro as André.) Their son and André’s best friend is Philippe de Valmorin (Richard Anderson), the pamphleteer Marcus Brutus who has been advocating a usurping of the aristocracy.

Leaving Lenore with the promise of procuring the ring, André arrives at the home of a couple he has treated like his own parents. (Lewis Stone, the husband, played Marquis de Maynes in the 1923 silent version of Scaramouche, with Ramon Novarro as André.) Their son and André’s best friend is Philippe de Valmorin (Richard Anderson), the pamphleteer Marcus Brutus who has been advocating a usurping of the aristocracy.

When André learns that the stipends from his substitute father have ceased, he coerces the intermediary lawyer Fabian (Curtis Cooksey) to reveal his real father, a nobleman named Duc de Gavrillac. Moreau sets out for Normandy to find him and on the way encounters Aline’s disabled coach. He delivers one of the best lines, typical of the film’s flippant humor: “Happy is the rascal, traveling life’s byways, to whom the gods say, here is an easy switch. You may have lost Diana on the highway, but, look, there is Aphrodite in a ditch.” “Molière?” she asks. “Moreau,” he replies.

If I may, a little lingering on this scene, one of my favorites, while André woos Aline in the coach, as he had earlier wooed Lenore in the hansom. Turning on the charm, André presumes to read her palm—and divine where she’s going and why, and her name, which he can almost see on an embroidered pillow on the seat beside her. The ornate lettering is partially hidden by her nervous, patting hand. “I can almost see your name,” he envisions. “Gav—” “Yes, yes! ” she gasps anxiously. “Gav-ri—” “Go on!” In desperation, he removes her hand to say, “Gavrillac,” then to exclaim, “Gavrillac?!” Aline might have been impressed by his charm, but it’s all for nothing. She is his sister!

If I may, a little lingering on this scene, one of my favorites, while André woos Aline in the coach, as he had earlier wooed Lenore in the hansom. Turning on the charm, André presumes to read her palm—and divine where she’s going and why, and her name, which he can almost see on an embroidered pillow on the seat beside her. The ornate lettering is partially hidden by her nervous, patting hand. “I can almost see your name,” he envisions. “Gav—” “Yes, yes! ” she gasps anxiously. “Gav-ri—” “Go on!” In desperation, he removes her hand to say, “Gavrillac,” then to exclaim, “Gavrillac?!” Aline might have been impressed by his charm, but it’s all for nothing. She is his sister!

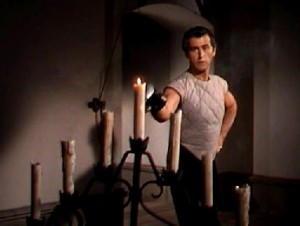

Next scene, Philippe and André are lounging at a tavern, Moreau recounting his unsettling discovery about Aline, when they are interrupted by Noel and his henchman, Chevalier de Chabrillaine (Henry Wilcoxon). The marquis accuses Philippe of being the radical Marcus Brutus and kills him in a duel. André, with no knowledge of the sword, vows vengeance and escapes. While hiding out in the comedy troupe and assuming the role of the masked clown Scaramouche (Henry Corden), he secretly takes fencing lessons from two master swordsmen, first Doutreval (John Dehner) and then Perigore (Richard Hale).

Next scene, Philippe and André are lounging at a tavern, Moreau recounting his unsettling discovery about Aline, when they are interrupted by Noel and his henchman, Chevalier de Chabrillaine (Henry Wilcoxon). The marquis accuses Philippe of being the radical Marcus Brutus and kills him in a duel. André, with no knowledge of the sword, vows vengeance and escapes. While hiding out in the comedy troupe and assuming the role of the masked clown Scaramouche (Henry Corden), he secretly takes fencing lessons from two master swordsmen, first Doutreval (John Dehner) and then Perigore (Richard Hale).

Once he has acquired what he feels is the necessary prowess with the rapier, Moreau enters politics upon the encouragement of Dr. Dubuque (John Litel) and joins the National Assembly, intending to challenge de Maynes, who is also a member of the assembly. Strangely, the marquis is always absent. The two women, Lenore and Aline, now aware of one another, join forces; Lenore informs on André’s activities and Aline arranges for Noel to be sent on any number of administrative inspections of convents and waterworks.

The day comes, though, when the two men’s paths cross. During a performance of Binet’s troupe, André removes his Scaramouche mask and challenges the marquis to a duel. Swinging from ropes, teetering on balcony railings, bounding down staircases, springing off sofas, crashing through backstage sets, the men parry, thrust and flèche in the longest duel in film history—and done without music!

The day comes, though, when the two men’s paths cross. During a performance of Binet’s troupe, André removes his Scaramouche mask and challenges the marquis to a duel. Swinging from ropes, teetering on balcony railings, bounding down staircases, springing off sofas, crashing through backstage sets, the men parry, thrust and flèche in the longest duel in film history—and done without music!

The movie ends in a triple surprise, none of which will be divulged here . . . oh, all right, just one: Aline is not André’s sister! How ’bout that?!

But a duel “done without music”!? The producers, perhaps the director, must have decided there should be no music here, disregarding the challenge set by Korngold in Errol Flynn’s three great, music-supported duels—in Captain Blood (okay: mostly Liszt’s Prometheus tone poem), The Adventures of Robin Hood and, that epitome of rapier rousting, The Sea Hawk. Maybe, even, Victor Young, being somewhat lazy, decided the fight would require too much fast music, which always takes more paper and more time to write than slow music, or maybe the composer had that date, either with a woman or a bottle. Those were among his vices, along with smoking, and he would die at fifty-seven.

Beginning with a crescendo and heroic fanfare, the main title immediately announces the kind of adventure we can expect. It is one of the incongruities of Hollywood film music that the main title of Alfred Newman’s All About Eve should produce a similar image of outdoorishness and high adventure for a film that evolves, totally different in tone, as a contemporary, backstage melodrama. But there is no deception here. With brilliant, unison horns, timpani raps and spiraling strings, all is bustle, all is splashing color.

Beginning with a crescendo and heroic fanfare, the main title immediately announces the kind of adventure we can expect. It is one of the incongruities of Hollywood film music that the main title of Alfred Newman’s All About Eve should produce a similar image of outdoorishness and high adventure for a film that evolves, totally different in tone, as a contemporary, backstage melodrama. But there is no deception here. With brilliant, unison horns, timpani raps and spiraling strings, all is bustle, all is splashing color.

Throughout the film, Lenore’s theme, in contrast with the more reserved and delicate one for Aline, swoons through two distinctive upward leaps that convey her passionate, liberated and earthy nature. Both tunes are typical of Young, Lenore’s so lushly romantic that it cries out for words. The music to accompany the theatrical performances—I have in mind a pavane-like episode and that for the magic box where actors, mainly Lenore and Scaramouche, materialize with the swoop of a wand—have, properly, an almost eighteenth-century feel to them.

When sorrowful or gloomy music—there is a difference, I think—is required, as in the cello solo that underpins Aline’s father’s death, or at the end of film when André asks over and over “Why?,” Young is possibly at this best. By contrast, the opening clamor of de Chabrillaine’s galloping horse troop and that for Moreau’s equestrian escape from de Maynes are somewhat mechanical, seemingly made intentionally unmemorable, as if Young is marking time for the next lyrical cue. The end cast, one of the best around, is an exhilarating waltz. You wish it could continue a little longer.

Among available original soundtrack recordings, there is Film Score Monthly’s fine complete, though mono release including deleted and alternate material, and, of course, any number of pirated versions, usually in terribly transferred sound. A recently recorded stereo version I recommend, although reduced to an eighteen-minute suite, is the Naxos CD (8.557704), with Richard Kaufman conducting the Brandenburg Philharmonic Orchestra of Potsdam, previously released in 1995 under the Marco Polo label (8.223607).

This Scaramouche suite represents the absolute best from the score and, indeed, as an entity, provides an esthetically satisfying musical experience, which can’t be said about all movie scores. After that final chord—and, yes, the enchanting end cast closes the suite—the music might even leave an impression of the young Richard Strauss, say, Don Juan, or, later, the fifty-four-year-old Strauss writing with juvenile verve the incidental music to Molière’s play, Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, which includes a fencing master and has a comic spirit similar to Scaramouche.

The Scaramouche score is authentically reconstructed by William Stromberg and recorded with crystal clear vitality by engineer Gert Puhlmann, who sumptuously captures the heavily worked French horns, a Young mainstay, with particular attention to the bright xylophone. The suite is part of a compilation of derring-do scores, even, more specifically, films involving—fencing. Two of the other scores, Miklós Rózsa’s The King’s Thief and Max Steiner’s The Three Musketeers (1935), boast a similar sound integrity, but the fourth score, and perhaps the most substantial, Korngold’s Captain Blood, must have been recorded on another day (the two recording sessions were two months apart); for whatever the reason, the acoustics suddenly has a brittle edge. Most unfortunate for an otherwise splendid disc.

In the spirit of the rollicking Scaramouche and in tribute to Victor Young, who had a wild sense of humor and loved practical jokes, here is an excerpt from Tony Thomas’ highly recommended book Music for the Movies:

“Young and Max Steiner were the closest of friends, and similar kinds of men—lovers of poker and horse racing and other things. On one occasion Young drove up from Paramount to have lunch with Steiner at Warners. Arriving at the studio shortly before noon, he wandered over to the music department and found Steiner rehearsing the orchestra in the main title of a new film. Hearing what was a typical but distinct Steiner theme, Young had an idea. He, unseen by Steiner, wrote the theme on a piece of paper, left the recording stage, got into his car and drove back to Paramount. Within a couple of hours, Young had made an orchestral sketch of what he had just heard, and the following morning he recorded the piece with his own orchestra.

“

He then called Steiner and invited him to his house that evening for a poker session. By the time Steiner and a pair of other card-playing musicians arrived, Young had wired his record player to his radio. Some time during the game, he switched on the radio, which triggered the record player—and out came the Steiner music. After about twenty seconds, Steiner’s eyes came up from his cards and he started to tremble. ‘Oh, my God.’ ‘What’s wrong, Max?’ innocently asked Young. Steiner shook his head. ‘I don’t understand. That music. Is that something new?’ ‘Hell no,’ said Young, ‘I listen to this program all the time—they’ve been playing it for years.’ Steiner tried to pick up the game but his attention was destroyed. Soon he said, ‘Vic, I’m not feeling too well. I’d better go.’ ”

Finally, André Moreau may well be Stewart Granger’s greatest role—I for one am not about to challenge that—for, like Errol Flynn in a way, he seems best in period and historical pictures, i.e., Beau Brummell, The Magic Bow (as Paganini), Footsteps in the Fog, the 1952 remake of The Prisoner of Zenda, Young Bess (as Thomas Seymour), Moonfleet and other titles. Granger, in fact, becomes André Moreau so easily, and with such tongue-in-cheek levity, that the role seems more a reflection of himself. While the other major stars generally play it straight, both Granger and Eleanor Parker become—what is the cliché?—“larger than life,” their performances perhaps bordering on “over the top.” Although the film already has plenty of zest, these two stars add that extra spice, the topping on a delectable soufflé.

An aberration, an anomaly, a misnomer and that other word again? An anachronism. What if Scaramouche, among its companion films of 1952, is all of these things? It’s a fun movie, meant to be enjoyed. So—enjoy! And remember what André Moreau has said about his fencing lessons, more proof of what he suspects about the mental state of the world:

“I can no longer be taught by the man who taught my enemy. So, what is more fitting in a mad world, then to be taught by the man who taught the man who taught my enemy!”