“The tale hinges, like so much in humanity’s sorry history, on a piece of paper. In this case no broken treaty or injudicious epistle from one Personage to another, but a slip upon which Adrian Messenger wrote the names and addresses and occupations of ten men.”—— the third paragraph of The List of Adrian Messenger

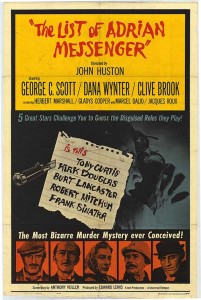

Universal issuing The List of Adrian Messenger on DVD, now in the “Vault Series” (individually burned on request), is excuse enough to write about director John Huston’s little mystery, released in 1963. It’s one of my Top Ten favorite films despite some grumblings over the years by some critics about its weaknesses.

At the time of its release, two disparate views appeared that still persist—first, as exemplified by the New York Times, that “ . . . Mr. John Huston [getting] mixed up with this deception . . . is hard to understand”; and, second, according to Newsweek, “The program of murders . . . is merely a framework for John Huston’s clever work. John Huston has had a good time, and he lets his audience in on it.” I’m with the latter.

Except for a change in the murderer’s dispatch in the end, the film is generally faithful to Philip MacDonald’s enthralling mystery, published in 1959. As was typical of Huston after an exhausting film, List was a deliberate relaxation after the difficult and financially unsuccessful Freud, and was quickly and efficiently made in England and Ireland, where the director was living at the time. The subsequent movie, The Night of the Iguana, would be one of John Huston’s best.

The major point of contention regarding the integrity of List, apart from an occasional script gaff and some awkward over-dubbing, is Bud Westmore’s make-up. For Kirk Douglas, it is an essential part of both novel and movie, as his character (George Brougham) is killing his victims and eluding discovery in ever-changing disguises. But for Burt Lancaster, Tony Curtis, Frank Sinatra and Robert Mitchum it is a distraction, part of a gimmick John Huston devised to see if his audience could spot the stars. Well, spotting them isn’t hard. The make-up is heavy and unrealistic, acutely obvious beside actors who aren’t made up.

The most recognizable of all despite the make-up, and with no attempt to mask that distinctive voice, Robert Mitchum should not have been part of the stunt, as his character is integral to the plot. It was rumored that Frank Sinatra in his one scene as a gypsy wasn’t even under the Westmore make-up, which may explain why, in this case, the actor’s features are totally unrecognizable.

The most recognizable of all despite the make-up, and with no attempt to mask that distinctive voice, Robert Mitchum should not have been part of the stunt, as his character is integral to the plot. It was rumored that Frank Sinatra in his one scene as a gypsy wasn’t even under the Westmore make-up, which may explain why, in this case, the actor’s features are totally unrecognizable.

Too much time spent on minor points, perhaps, for the film is a good mystery after all, even though that same New York Times review regarded it as “plainly mediocre.” It is not that, I assure you, though, admitted, the movie is not for viewers used to the “watching pace” of many current productions, with explosions, special effects, car chases and rapid editing; quite the contrary, there are numerous extended scenes of quiet, plot-essential dialogue. This is the kind of film that requires repeated viewings to fully understand its story line—and to appreciate its subtle qualities.

The interest is in the details—the patient unraveling of clues, some of the best fox-hunting on film, extended scenes of clue analysis, an excellent score by Jerry Goldsmith and a distinguished supporting cast. List would be the last film for Herbert Marshall and for Clive Brook, coaxed out of a twenty-year retirement by Huston—and nearly the last for Gladys Cooper, who would have a small part in My Fair Lady the following year. Dana Wynter is the “British,” German-born beauty on hand. Canadian John Merivale, stepson of Gladys Cooper and Vivien Leigh’s lover following her divorce from Laurence Olivier, is the title character, whose passions are fox hunting and writing.

All the major stars have been mentioned except two, and the one with top billing creates another sticking point. George C. Scott as Anthony Gethryn, semi-retired sleuth of MI-5, is supposedly British but his accent comes and goes. This “flaw,” when put out of mind, like the make-up gimmick, does not hinder success, in this case a legitimately effective performance from George C. Scott, with a touch of British reserve, whether intended or not.

All the major stars have been mentioned except two, and the one with top billing creates another sticking point. George C. Scott as Anthony Gethryn, semi-retired sleuth of MI-5, is supposedly British but his accent comes and goes. This “flaw,” when put out of mind, like the make-up gimmick, does not hinder success, in this case a legitimately effective performance from George C. Scott, with a touch of British reserve, whether intended or not.

Not all that common in the ’60s as it is today, the film begins before the credits. With Jerry Goldsmith’s appropriate “villain” music, which recurs whenever he is present, a man enters an apartment building and malfunctions the elevator so that its lone occupant crashes to the basement. It’s not the first, it’s only another victim, whose name the man scratches off a list which also includes Adrian Messenger’s.

Following the credits, presumably the same man, now on a bicycle and wearing a clerical collar, approaches the country estate of Simon Bruttenholm, Marquis of Gleneyre (Brook). He carries the same Baedeker’s Great Britain guide book used to jam the elevator door. From a distance, he watches the horsemen and hounds depart for a fox hunt, with hints of the melodies and rhythms Jerry Goldsmith will later rousingly employ in two extended hunting sequences.

Following the credits, presumably the same man, now on a bicycle and wearing a clerical collar, approaches the country estate of Simon Bruttenholm, Marquis of Gleneyre (Brook). He carries the same Baedeker’s Great Britain guide book used to jam the elevator door. From a distance, he watches the horsemen and hounds depart for a fox hunt, with hints of the melodies and rhythms Jerry Goldsmith will later rousingly employ in two extended hunting sequences.

After the hunt, before the fireplace, the Marquis and his guests digest the day’s hunt. He mentions that in America they use a drag, the odor of a fox dragged over the ground to lay a false scent for the hounds. “Ruins their noses!” he exclaims—and even alludes to a brother in Canada, who, he says, is now probably dead. “Almost everyone is!” Messenger hands Gethryn a list of “ten names, ten probable occupations, ten addresses,” scattered across England, and requests him to “ask about them”—verify if they’re living at those addresses—while he’s in Canada for two weeks. Gethryn accepts. “Of course, old boy.”

In the next scene, Messenger checks his baggage at an air terminal. In line behind him is the clergyman seen earlier, introducing himself as a Reverend Attlee, whose luggage is overweight. Adrian suggests that, since his luggage was under the limit, the vicar’s overage be added to his own. “How uncommonly kind,” Attlee says. Behind the vicar is a man the air line clerk recognizes. “Good evening, Mr. Le Borg (Jacques Roux).” A frequent flyer, perhaps?—and clearly in better days of air travel!

In the next scene, Messenger checks his baggage at an air terminal. In line behind him is the clergyman seen earlier, introducing himself as a Reverend Attlee, whose luggage is overweight. Adrian suggests that, since his luggage was under the limit, the vicar’s overage be added to his own. “How uncommonly kind,” Attlee says. Behind the vicar is a man the air line clerk recognizes. “Good evening, Mr. Le Borg (Jacques Roux).” A frequent flyer, perhaps?—and clearly in better days of air travel!

Moments later the vicar enters a restroom and promptly, slowly, carefully removes his face, revealing for the first time Kirk Douglas’. With no dialogue to obstruct, Goldsmith weaves his sinister music, underscoring the removal of now eye sockets, now false teeth, now a hairpiece and, finally, the thin mask with its elastic glue. The music buzzes and trills over a murky rumble, with an allusion to the “villain” theme; it is almost Herrmann-like in its non-melodic, motif-based milieu. Kirk Douglas, now as a different character—the third, if you’re counting—emerges from the restroom and leaves the terminal while the Reverend Attlee is being paged to report for his flight.

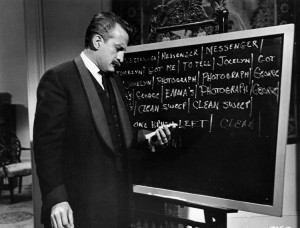

Soon after becoming airborne, the plane explodes over the Atlantic. Clinging to a piece of debris in the sea is Adrian and Le Borg, who overhears what he thinks are Adrian’s dying words: “Jocelyn—got me, too—tell Jocelyn. Photograph! Photograph! George, Emma’s. George, Emma’s. All the brooms. Clean sweep. Only one broom left. Clean sweep. Clean sweep——” Adrian Messenger dies.

Soon after becoming airborne, the plane explodes over the Atlantic. Clinging to a piece of debris in the sea is Adrian and Le Borg, who overhears what he thinks are Adrian’s dying words: “Jocelyn—got me, too—tell Jocelyn. Photograph! Photograph! George, Emma’s. George, Emma’s. All the brooms. Clean sweep. Only one broom left. Clean sweep. Clean sweep——” Adrian Messenger dies.

At Scotland Yard, Sir Wilfred (Marshall) informs Gethryn that a Frenchman, Raoul Le Borg, smelled cordite, indicative of a bomb. Gethryn suggests that no one should know more about explosives, as Le Borg was in the French Resistance during WWII, blowing up countless bridges and marshalling yards, “a thorn in the side of the German occupation.” Just coincidentally, Gethryn had served with him, but only through the short wave. What’s more, Gethryn announces the results, so far, of his verification of Adrian’s list: six of the individuals are dead—all killed in accidents. A detective enters the room to confirm a seventh victim, he, too, killed in an accident.

Recovering in the hospital from his fall into the sea, Le Borg is visited by Lady Jocelyn Bruttenholm (Wynter), who has come to thank him for his effort to save her cousin. Gethryn arrives as well, and Le Borg recalls Messenger’s last words, which Gethryn writes down in his notebook. From his memory, Le Borg unknowingly substitutes “brush” for Messenger’s actual word “broom.” Perhaps a small matter, perhaps not.

Gethryn later deduces that what Le Borg heard as “Emma’s” is actually “MS,” the abbreviation for manuscript, that, put together, Messenger was saying there are photographs of George—whoever “George” is—in his manuscript. It is interesting here, plus indicative of the excellent screenplay by Anthony Veiller, a writer-friend of Huston’s, that the crux of this multifaceted mystery is the misinterpretation of several key words, one in particular, and what might be seen as an unfair withholding from the audience of critical information. More later. . . .

Adrian’s cat introduces a scene not in the book. In Messenger’s Mayfair flat, our villain—we know that because of the “villain” music and the pasty make-up!—is concluding his work at Adrian’s desk when Jocelyn enters. The man, now baldheaded and exhibiting a mousy persona, introduces himself as Mr. Pythian, a resident at the hotel looking in on the cat. (Unusual that Jocelyn never questions how the man gained entry to the flat!) After some small talk about cats and Pythian’s casual acquaintance with Messenger, the man leaves.

Gethryn and Le Borg arrive and examine Messenger’s manuscript. Gethryn asks Jocelyn and the Frenchman to examine page 174. What’s different about it compared with pages 101 and 135? Humm—— Why, yes, she notices that the page is a line or two shorter than the others. “And that’s not all,” Gethryn says: all the capital letters are slightly elevated and there’s no space after the semicolons, done on the same typewriter but not by the same typist. Which means?— Which means that someone had entered the flat and retyped the list of men in Messenger’s unit in Burma during WWII, that perhaps one name was deleted. Then Jocelyn remembers—— “Mr. Pythian!”

Gethryn and Le Borg arrive and examine Messenger’s manuscript. Gethryn asks Jocelyn and the Frenchman to examine page 174. What’s different about it compared with pages 101 and 135? Humm—— Why, yes, she notices that the page is a line or two shorter than the others. “And that’s not all,” Gethryn says: all the capital letters are slightly elevated and there’s no space after the semicolons, done on the same typewriter but not by the same typist. Which means?— Which means that someone had entered the flat and retyped the list of men in Messenger’s unit in Burma during WWII, that perhaps one name was deleted. Then Jocelyn remembers—— “Mr. Pythian!”

After two more men on Messenger’s list have been accounted for as dead, one survivor remains, a James Slattery (Robert Mitchum). Gethryn tracks him to a tobacco shop, where, come to find out, the man is not James but his wheelchair-bound brother Joe, whose WWII experience was limited to Europe. Joe says that his brother died from a heart attack. “Keeled over like a canary.”

Darn! Dead end for Gethryn. He waves away an organ grinder, a surveillance policeman who had been placed outside Slattery’s shop. Tony Curtis, in his Westmore make-up, had an earlier scene in which Slattery told him to cease his annoying music.

But after Gethryn leaves, Slattery moves beyond a curtain, which is closed by his mother (Anita Bolster, perhaps best remembered as the bearded lady in Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur, and who has too large a role in List to go uncredited). Slattery rises from his wheelchair and exercises his cramped legs—seen in close-up by Joseph MacDonald’s camera—while Mrs. Slattery, in a long shot, warns him that he’ll never get away with posing as his brother Joe.

Th e disguise, however, does not deceive the villain in his “mass murder plot so preposterous as to defy belief,” as Sir Wilfred has called it. Now impersonating a waterfront idler, he follows Slattery from a bar, knocks him in the head and pushes him from a boardwalk into the sea. (The keen viewer will see Mitchum’s stand-in clutch the back frame of the wheelchair.)

e disguise, however, does not deceive the villain in his “mass murder plot so preposterous as to defy belief,” as Sir Wilfred has called it. Now impersonating a waterfront idler, he follows Slattery from a bar, knocks him in the head and pushes him from a boardwalk into the sea. (The keen viewer will see Mitchum’s stand-in clutch the back frame of the wheelchair.)