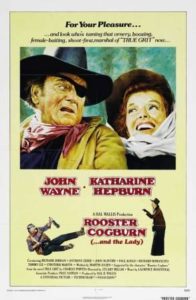

The man of “True Grit” is back and look who’s got him!

Often called the sequel to True Grit, Rooster Cogburn bears little resemblance to perhaps John Wayne’s most popular- even if not best, role. In the almost thirty years since its release, it has joined Wayne’s other 1970s films as a key component in a relative mélange of mediocrity.

Wayne is clearly laboring here, and rightfully so. He well into the sunset of his career, but still trying to compete with newer and hotter stars of the time, namely Clint Eastwood and Burt Reynolds. He’d even gone so far as to dip his toes into their type of movies, resulting in the tepid McQ and Brannigan in 1974 and 1975. Surprisingly, he was still the #1 draw at the box office in 1971, the year Big Jake was released. It was his last hit picture.

Not only were things tougher due to Wayne’s age and America’s changing interests away from westerns, but his health was also questionable. In addition to increasing infirmities from his increasing old age, he had lost a lung in 1964 to cancer and suffered a stroke in 1974. The former required Wayne to have oxygen available at all times during filming Rooster Cogburn, though Wayne’s needs here were exacerbated by the elevation (in Oregon) where most of the filming took place. The stroke required Wayne to alter his speech pattern and speak out of the side of his mouth. This pattern is especially noticeable in Coogburn and its predecessor, Brannigan.

Not only were things tougher due to Wayne’s age and America’s changing interests away from westerns, but his health was also questionable. In addition to increasing infirmities from his increasing old age, he had lost a lung in 1964 to cancer and suffered a stroke in 1974. The former required Wayne to have oxygen available at all times during filming Rooster Cogburn, though Wayne’s needs here were exacerbated by the elevation (in Oregon) where most of the filming took place. The stroke required Wayne to alter his speech pattern and speak out of the side of his mouth. This pattern is especially noticeable in Coogburn and its predecessor, Brannigan.

So how does the end result fare?

Nostalgic, but rather weak, Rooster Cogburn is in many ways simply a westernized African Queen, with Wayne and co-star Katharine Hepburn floating downriver with an explosive final act in store. Unlike his earlier films (think Rio Bravo), Wayne isn’t paired with a young heartthrob to garner box office cache. If anything, the somewhat odd pairing with Hepburn did nothing but diminish any attraction a younger audience may have had for the film.

Nostalgic, but rather weak, Rooster Cogburn is in many ways simply a westernized African Queen, with Wayne and co-star Katharine Hepburn floating downriver with an explosive final act in store. Unlike his earlier films (think Rio Bravo), Wayne isn’t paired with a young heartthrob to garner box office cache. If anything, the somewhat odd pairing with Hepburn did nothing but diminish any attraction a younger audience may have had for the film.

Even the score, here by Laurence Rosenthal, harkens back to an earlier picture. It bears more than a slight resemblance to the score from the much earlier Big Country.

The plot seems to try to take the advanced age of the stars into account. Ignoring the fact that both (Wayne especially) were far to aged at the time to be appropriate for their roles, there are several surprisingly witty and self-deprecating comments sprinkled throughout. In one of the better scenes of the picture (of which there are few), Wayne is humorously mocked by Judge Parker, with whom he clearly has had a career-long relationship. Parker mocks Cogburn’s appearance, saying he drinks too much and has let himself go to seed. Wayne’s reply of “I ain’t had a drink since breakfast” strikes a great chord.

The plot seems to try to take the advanced age of the stars into account. Ignoring the fact that both (Wayne especially) were far to aged at the time to be appropriate for their roles, there are several surprisingly witty and self-deprecating comments sprinkled throughout. In one of the better scenes of the picture (of which there are few), Wayne is humorously mocked by Judge Parker, with whom he clearly has had a career-long relationship. Parker mocks Cogburn’s appearance, saying he drinks too much and has let himself go to seed. Wayne’s reply of “I ain’t had a drink since breakfast” strikes a great chord.

Rooster Cogburn (Wayne): How old are you?

Eula Goodnight (Hepburn): Shall we say it has already struck midnight?

Throughout the picture, any scene with Richard Jordan is worth the price of admission. As the dastardly renegade Hawk, his self-labeled over the top performance steals the show. Thinking the movie was swill and any draw would be purely because of Wayne’s and Hepburn’s names on it, he ramped up his performance. His remains a bright spot in an otherwise flat outing. Incidentally, Jordan though Hepburn might drop dead at any moment during filming, though ironically she outlived him by many years.

Throughout the picture, any scene with Richard Jordan is worth the price of admission. As the dastardly renegade Hawk, his self-labeled over the top performance steals the show. Thinking the movie was swill and any draw would be purely because of Wayne’s and Hepburn’s names on it, he ramped up his performance. His remains a bright spot in an otherwise flat outing. Incidentally, Jordan though Hepburn might drop dead at any moment during filming, though ironically she outlived him by many years.

As I mentioned above, the film is a westernized remake of the Bogart-Hepburn classic The African Queen- just substitute a western motif. Wayne (Cogburn) is hot on the trail of Hawk’s gang after they kill the father of missionary Hepburn (Eula Goodnight). They have some witty banter as they travel up the mountains and down again, only to float down the river on a raft in hot pursuit of Hawk and his cronies. The raft segment bears (of course) the most similarities to Hepburn’s prior film, leveraging nitro-glycerin and a gatlin gun against the Queen’s torpedoes.

As I mentioned above, the film is a westernized remake of the Bogart-Hepburn classic The African Queen- just substitute a western motif. Wayne (Cogburn) is hot on the trail of Hawk’s gang after they kill the father of missionary Hepburn (Eula Goodnight). They have some witty banter as they travel up the mountains and down again, only to float down the river on a raft in hot pursuit of Hawk and his cronies. The raft segment bears (of course) the most similarities to Hepburn’s prior film, leveraging nitro-glycerin and a gatlin gun against the Queen’s torpedoes.

Incidentally there is another amusing tidbit of conversation when the gun washes overboard through some rapids (still another Queen reference) as Hepburn wails that they’ve lost the gun in the river. Wayne’s sardonic reply is (roughly), “Well what the hell do you think I can do about it?”

Hepburn and Wayne seem to have an odd type of chemistry in their only onscreen pairing. Though both are a bit crotchety, they seem to have an inside knowledge that this isn’t their best entry in their respective filmographies. They are having a bit of fun with the material, and one gets the impression that they’d like you to be in on the joke.

Hepburn and Wayne seem to have an odd type of chemistry in their only onscreen pairing. Though both are a bit crotchety, they seem to have an inside knowledge that this isn’t their best entry in their respective filmographies. They are having a bit of fun with the material, and one gets the impression that they’d like you to be in on the joke.

There are hints of a potential romantic storyline between the two stars, but thankfully it is never really developed. The closest it ever comes to reality is Wayne’s comment (to Hepburn) towards the denouement, “Being around you pleases me.”

And that is probably the best way to sum up the movie. The nostalgic feel of the two iconic stars offsets the unoriginal script.

And that is probably the best way to sum up the movie. The nostalgic feel of the two iconic stars offsets the unoriginal script.