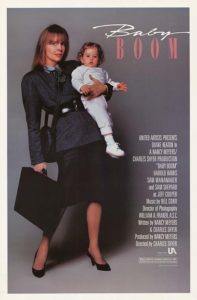

“I can’t have a baby because I have a twelve-thirty lunch meeting.”—— Diane Keaton as J.C. Wiatt

Hardly an old “classic movie,” and, probably, not likely to become one, however long the future, but Baby Boom, despite its clichéd plot, is practically carried, single-handed, by the effervescent, ever-eccentric Diane Keaton. She almost always manages a commanding presence in her films, even when her supporting players, and sometimes the movies themselves, give less than she does.

Best remembered, so far, for her roles in the Godfather films and the eight directed by Woody Allen, the approaching-seventy actress, a free spirit on screen and in life—she had relationships with both Allen and Warren Beatty, starring in the latter’s Reds—has made a trademark of wearing white, suits, ties and hats. Ever seen her on talk shows? Well, you know. Her eccentricities, her flamboyant body language, outspoken comments and, yes, that perpetual sparkle, make her the Katharine Hepburn of today. (Well, maybe Hepburn didn’t always “sparkle” off screen.)

Diane Keaton is definitely, dramatically a modern lady. That is, if one is familiar with her films, most of which are set in the present, it seems absurd to imagine her in, say, an historical drama. One of the few period pictures she made, also directed by Allen, is Love and Death, about a scheme to assassinate Napoleon; it is totally successful, perhaps because it is a comedy, with history treated as a farce, as it often becomes in the distortions of many a history book.

Keaton, then, is clearly herself in Baby Boom, contemporary and practical and larger-than-life. She owns the property, so to speak. And this screen adventure is worthy of her style and persona only because she makes the most of—even surmounts—the somewhat limited range of the material. The movie is an advanced take on the Doris Day films of the ’60s in which, most of the time, that actress is quite content to be a housewife. Sans the virginal schoolgirl grin and the antiseptic touches upon sexuality, Day’s That Touch of Mink comes the closest to Baby Boom in its imperfect sophistication.

Keaton, then, is clearly herself in Baby Boom, contemporary and practical and larger-than-life. She owns the property, so to speak. And this screen adventure is worthy of her style and persona only because she makes the most of—even surmounts—the somewhat limited range of the material. The movie is an advanced take on the Doris Day films of the ’60s in which, most of the time, that actress is quite content to be a housewife. Sans the virginal schoolgirl grin and the antiseptic touches upon sexuality, Day’s That Touch of Mink comes the closest to Baby Boom in its imperfect sophistication.

The place of the woman in the workplace of the 1980s, the theme which Baby Boom immediately and rather flagrantly establishes, complete with a documentary-style opening narration by journalist Linda Ellerbee, is subtly perpetuated in the remainder of the film by a quirk of the plot. Right off, her character loses it all, but at the end, in a plot about-face, she gets it all back, and more, possesses what the opening scenario set down as unobtainable for a woman—job and family.

J. C. Wiatt (Keaton), a high-wire business executive slated for a partnership with the boss, Fritz Curtis (Sam Wanamaker), of Sloane, Curtis and Company, is later denied an advanced position because becoming a “mother” has distracted her from her job. She’s “lost her focus,” as Curtis says. Not only that but an eager beaver (James Spader), craving that key to the executive washroom, is quick to take advantage of the situation and ease her out.

See, Wiatt is not really a “mom” in the biological sense—Keaton herself has never married—and this interruption in her job focus is the inheritance of a baby from a distant relative. Baby Elizabeth (alternately twins Kristina and Michelle Kennedy) is a cutie, as most babies are, and there is almost an immediate bond. Wiatt surrenders to the little one’s charms before she realizes it, lugging home a carload of essential baby things. Her live-in boyfriend (Harold Ramis), a specialist in five-minute copulations, wants no part of playing father, or, for that matter, helping to make a baby himself. This intrusion on his space was not part of their living arrangement.

See, Wiatt is not really a “mom” in the biological sense—Keaton herself has never married—and this interruption in her job focus is the inheritance of a baby from a distant relative. Baby Elizabeth (alternately twins Kristina and Michelle Kennedy) is a cutie, as most babies are, and there is almost an immediate bond. Wiatt surrenders to the little one’s charms before she realizes it, lugging home a carload of essential baby things. Her live-in boyfriend (Harold Ramis), a specialist in five-minute copulations, wants no part of playing father, or, for that matter, helping to make a baby himself. This intrusion on his space was not part of their living arrangement.

After his departure, in an effort to put her career back on course, J.C. interviews babysitters. She goes through a myriad collection of odd individuals. The first prospect, when asked, “What brought you to New York?,” replies, “The Lord.” “A-ha,” J.C. responds. “Well, er, thanks very much for coming by.” The final choice, perhaps no better, is a severe taskmistress (Carol Gillies), a German from Wiesbaden.