The most baffling mystery ever tackled by the most fascinating sleuth since Sherlock Holmes!

It’s been done before—a puzzling riddle of a suicide worthy of Agatha Christie, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle or G. K. Chesterton. A dead man is found in a locked room. Only it isn’t suicide, it’s murder. After a brief look-see at Archer Coe, master sleuth Philo Vance deduces that suicide is impossible. For one, the man has been bludgeoned and shot. And stabbed—in the back. For another, suicide, the detective announces, is psychologically unlikely. Vance had seen Coe the day before and he was looking forward to his dog’s entry in the kennel show.

Coe’s brother, found stuffed in a closet, was also murdered that night in the same house—and, to further complicate things, a Doberman pinscher was found unconscious from a blow to the head.

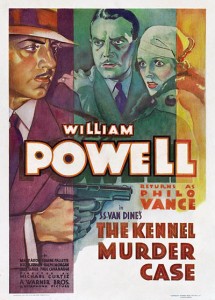

As might have been expressed in the crisp review style of the day—this, now, back in 1933—multifaceted writer S. S. Van Dine has joined Warner Bros.’ workhorse director [intlink id=”1579″ type=”category”]Michael Curtiz[/intlink] to make a “snappy-paced” whodunit, a regular “ripsnorter.” Creator of Philo Vance, Van Dine, now the screen writer, transfers one of his own novels, The Kennel Murder Case, to film. After the October premiere, a Variety critic rather blandly wrote, “Interesting and entertaining . . . a good picture.”

Rest assured, the movie is much more than that.

And much of its success belongs to [intlink id=”577″ type=”category”]William Powell[/intlink], in this the last—and best—of the four films he made in the series. In among the four, [intlink id=”128″ type=”category”]Basil Rathbone[/intlink], surprisingly not finding his depth in this detective, made a contrastingly snail-paced Bishop Murder Case. The subsequent films from various studios never captured the imagination or slickness of The Kennel Murder Case. Unfortunately, the various actors who played the detective ranged from, at worst, lackluster to, at best, ordinary. Warren William, Paul Lukas, James Stephenson, Alan Curtis, even Wilfrid Hyde-White in a British version and some others tried, but William Powell had set too high a standard. The series, from any studio, ended in 1947 and has never been revived, though there was an Italian TV mini series in 1974.

And much of its success belongs to [intlink id=”577″ type=”category”]William Powell[/intlink], in this the last—and best—of the four films he made in the series. In among the four, [intlink id=”128″ type=”category”]Basil Rathbone[/intlink], surprisingly not finding his depth in this detective, made a contrastingly snail-paced Bishop Murder Case. The subsequent films from various studios never captured the imagination or slickness of The Kennel Murder Case. Unfortunately, the various actors who played the detective ranged from, at worst, lackluster to, at best, ordinary. Warren William, Paul Lukas, James Stephenson, Alan Curtis, even Wilfrid Hyde-White in a British version and some others tried, but William Powell had set too high a standard. The series, from any studio, ended in 1947 and has never been revived, though there was an Italian TV mini series in 1974.

Powell, who about this time was ending his second marriage, after only two years with [intlink id=”1554″ type=”category”]Carole Lombard[/intlink], would make, in the next year, The Thin Man, the first of a six-film series that established him as one of the favorite stars of that Golden Age. Although other films—My Man Godfrey, The Great Ziegfeld and Life with Father—would bring him acclaim and Oscar nominations—never a win—he is best remembered as the Thin Man, actually Nick Charles.

For Powell, the Philo Vance films were, in reality, a dress rehearsal for the Thin Man. From the debonair, incisive, quick-talking detective Vance, he would become the debonair, incisive, quick-talking detective Nick Charles, though now with a warmer personality, a sense of humor and a fun-loving wife Nora (Myrna Loy). She was a much more able sleuthing partner than Sherlock Holmes’ bumbling Watson in the Rathbone/Nigel Bruce series.

William Reese is responsible for the occasionally fluid photography in The Kennel Murder Case—“occasionally” because most often it’s the actors who move for the camera, a holdover from the silent days, not all that distant in 1933. Reese has some claim to fame as cinematographer both on the first of the three Maltese Falcon versions—the 1931 one with Bebe Daniels and Ricardo Cortez—and, speaking of dogs, on the first of the Perry Mason series, The Case of the Howling Dog in 1934, with Warren William. Reese had a rebirth, or sorts, when his 1931 Murder at Midnight was used in the opening of The Mirror Crack’d. The sleuth in this case, Miss Marple, was played by Angela Lansbury.

William Reese is responsible for the occasionally fluid photography in The Kennel Murder Case—“occasionally” because most often it’s the actors who move for the camera, a holdover from the silent days, not all that distant in 1933. Reese has some claim to fame as cinematographer both on the first of the three Maltese Falcon versions—the 1931 one with Bebe Daniels and Ricardo Cortez—and, speaking of dogs, on the first of the Perry Mason series, The Case of the Howling Dog in 1934, with Warren William. Reese had a rebirth, or sorts, when his 1931 Murder at Midnight was used in the opening of The Mirror Crack’d. The sleuth in this case, Miss Marple, was played by Angela Lansbury.

In The Kennel Murder Case, the principal canines in the opening dog show are Scottish terriers, and Vance’s terrier, Captain McCavish, does not even place in his breed. (Franklin Roosevelt’s Scottish terrier, Fala, did not become a national celebrity until late 1940.) Although that Doberman would have a key role in identifying the killer, another dog, a wire-hair fox terrier, seen only briefly at the dog show, would become famous as Asta in the Thin Man series and receive screen credit. The Long Island Kennel Club event is not incidental to the plot, for at it and in the next scene are all of the suspects and victims.

The only member of the supporting cast who sometimes steals the limelight from Powell is Eugene Pallette (Friar Tuck in The Adventures of Robin Hood), back for another turn as the jovial and slightly dense sergeant Heath. He provides much of the humor in the film and always seems amazed by Vance’s deductions, yet elated, too, when the sleuth seems to stumble, though stumble he never does. As a running joke, Etienne Girardot holds his comic own as the animated, tart forensic doctor whose breakfast, lunch and dinner are interrupted by calls to examine bodies, dead and alive. He threatens to rent a room in the building until the case is solved.

The only member of the supporting cast who sometimes steals the limelight from Powell is Eugene Pallette (Friar Tuck in The Adventures of Robin Hood), back for another turn as the jovial and slightly dense sergeant Heath. He provides much of the humor in the film and always seems amazed by Vance’s deductions, yet elated, too, when the sleuth seems to stumble, though stumble he never does. As a running joke, Etienne Girardot holds his comic own as the animated, tart forensic doctor whose breakfast, lunch and dinner are interrupted by calls to examine bodies, dead and alive. He threatens to rent a room in the building until the case is solved.

Robert McWade as the district attorney spends most of his time agreeing with Vance’s evolving hypnoses. The following year he would reprise his role as D.A. Markham in another Philo Vance mystery, The Dragon Murder Case.

Robert Barrat (Wolverstone in Captain Blood) and Frank Conroy (Major Tetley in The Ox-Bow Incident) are the two murder victims.

[intlink id=”1045″ type=”category”]Mary Astor[/intlink], hardly the femme fatale here she would be in The Maltese Falcon (1941), shares roughly equal screen time with Helen Vinson, whose last appearance would be, ironically, the next-to-last film in the Thin Man series, The Thin Man Goes Home in 1944. She died some fifty-four years after her retirement, but not before making possibly her best film, Torrid Zone in 1940.

[intlink id=”1045″ type=”category”]Mary Astor[/intlink], hardly the femme fatale here she would be in The Maltese Falcon (1941), shares roughly equal screen time with Helen Vinson, whose last appearance would be, ironically, the next-to-last film in the Thin Man series, The Thin Man Goes Home in 1944. She died some fifty-four years after her retirement, but not before making possibly her best film, Torrid Zone in 1940.

Besides the two ladies, the other suspects are played by Paul Cavanagh (the passive husband in Humoresque), Ralph Morgan (Kurt Ingston in Night Monster), James Lee as the Chinese cook, Jack La Rue (Rata in The Sultan’s Daughter) and Arthur Hohl (Montgomery in Island of Lost Souls) as the butler. In this case, the butler didn’t do it!

Don’t be put off by the opening, which dates the film—the scrolling credits, the ancient Warner Bros.-Vitaphone Pictures flag trademark, the cameo inserts of the stars with their names and roles and the flat sound. Typical of most films of the day, there is little score beyond the main title and “The End.” The main title music is moderately impressive—by an uncredited Bernard Kaun, whose orchestrator, also uncredited, is Ray Heindorf.

Instead of explaining the criminal chain of events to a gathering of the suspects, as Nick Charles always does, Philo Vance expounds to sergeant Heath and D.A. Markham—without naming the murderer. He uses models of the houses, since the adjacent building plays a role in the solution. Vance knows the identity of the killer, but he has no proof, so he sets up a meeting with three of the suspects. One starts an argument and hits another, who reaches for a fireplace poker. Vance releases the Doberman, which recognizes the man who had attacked him the night of the murders. A confession follows with the usual, “I didn’t mean to do it.”

If the murder setups are a bit complicated, and, on careful analysis, border on the implausible, with numerous coincidences and a dumb murderer, the pace is snappy enough, and Powell is compelling enough, that it all doesn’t seem to matter. The other ingredients, some crisp dialogue, a good story and a fine cast, contribute to the overall satisfaction. That the mystery is unnecessarily convoluted merely adds to the fun and keeps the viewer on his toes.

And, oh, yes: Archer Coe was “killed” twice! Be sure and see The Kennel Murder Case and find out how that could happen. It remains today, a ripsnorter of a whodunit.