A disgruntled CIA man decides to take revenge on his boss and expose the transgressions of the agency.

The 1980s was a time of generally weak films for Walter Matthau. Behind him were two of his biggest hits, Charade (1963) and The Odd Couple (1968). In Mirage (1965) he is a sly detective working for amnesia victim Gregory Peck, in The Fortune Cookie (1966) a crooked insurance man in his third film for director Billy Wilder and in Grumpy Old Men (1993), a last hit, he is reunited in a final film with nine-time collaborator Jack Lemmon.

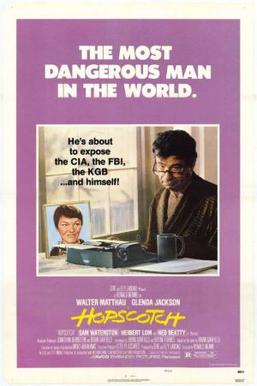

Hopscotch, a comedy-ized version of Brian Garfield’s serious and cynical novel about CIA shenanigans, becomes a deliberately hilarious cat-and-mouse caper. Matthau, in the grumpy, laid-back approach that made him famous, plays demoted CIA agent Miles Kendig who mails to spy agencies around the world his “memoirs,” exposing the ineptitude of boss Myerson (Ned Beatty) and the misdeeds of the agency.

Directed by one-time David Lean protégé Ronald Neame only on the understanding that the Garfield novel be a comedy, Hopscotch was filmed in a myriad of U.S. and international locations, including Georgia, Bermuda, Marseille and Calais, Salzburg, counties Kent and East Sussex in England as well as Mayfair and Heathrow Airport in London.

The plot is made romantically interesting with the scheme-necessary addition of Kendig’s accomplice/former girlfriend, Isobel. Glenda Jackson, who had appeared with Matthau in House Calls (1978), was pleased to work with the actor in a second film, and their chemistry is natural and genuine. The “R” rating is solely due to the abundant bad language.

The plot is made romantically interesting with the scheme-necessary addition of Kendig’s accomplice/former girlfriend, Isobel. Glenda Jackson, who had appeared with Matthau in House Calls (1978), was pleased to work with the actor in a second film, and their chemistry is natural and genuine. The “R” rating is solely due to the abundant bad language.

For the filming of the Munich Oktoberfest scene which begins the movie—done at the actual event with eight hidden cameras—Matthau only agreed to go to Germany if his son was cast, though this was David Matthau’s last of only eight theatrical films. Much like Artur Rubinstein, the great Polish pianist who never played in Germany after 1914, Matthau had lost family and friends in the Holocaust.

Since the actor loved Mozart’s music, always humming his tunes on the sets, the score is comprised of excerpts from Eine kleine Nachtmusik, the Piano Sonata No. 11 in A, the “Posthorn” Serenade and the Overture and the aria “Non più andrai” from The Marriage of Figaro.

Since the actor loved Mozart’s music, always humming his tunes on the sets, the score is comprised of excerpts from Eine kleine Nachtmusik, the Piano Sonata No. 11 in A, the “Posthorn” Serenade and the Overture and the aria “Non più andrai” from The Marriage of Figaro.

When the producers were undecided which piece to use for the various times—and in various world locations—when Kendig types his next memoir installment, the actor himself selected the Rondo in D, K382, for piano and orchestra. An ideal choice, rhythmic and heavily accented, it serves as the main theme of the “score,” its affirmative cadence also an appropriate ending for a number of scenes. (The film’s music editor is George Korngold, the late son of Erich Wolfgang Korngold who wrote so many splendid scores for Warner Bros.)

And the score contains as well other composers’ music, when scenes can benefit from an appropriate musical borrowing.

Although two spies were nabbed in passing-off microfilm at the Oktoberfest, Kendig earned his demotion from field agent to supervisor of files because he failed to arrest Russian agent Yaskov (Herbert Lom). Myerson screams athim, “You weren’t there to make policy; you were there to carry out policy.”

Having already stolen then shredded his personal CIA file, Kendig leaves Bavaria for Isobel’s home in Salzburg.

Having already stolen then shredded his personal CIA file, Kendig leaves Bavaria for Isobel’s home in Salzburg.

Yaskov and Kendig are like old friends in the espionage business. (It seems everyone likes Kendig—maybe that’s one reason why Myerson hates him.) So the Russian leaves his friend a bottle of vodka, note attached, to meet him at the fountain in the Mirabell Gardens (the partial location of the “Do-Re-Mi” sequence in The Sound of Music, 1965).

Aware they’re being photographed—“Yours or mine?” Kendig wonders—Yaskov offers a job in his KGB while Kendig shares the gifted vodka in mini wine glasses. When Yaskov is turned down and asks what Kendig will do now, “write your memoirs?,” Kendig rushes back to Isobel with an idea.

“You got a typewriter?” he asks her. “Find me a copy machine. Get me a stack of 9” x 12” Manila mailing envelopes.” And thus begins his memoirs—and Mozart’s rondo!

Next move for Kendig: Switzerland. As he drives through the checkpoint from Austria, he sings “Largo al Factotum” from The Barber of Seville. The guard mistakes Rossini’s Figaro for Mozart’s and Kendig corrects him.

Although protesting that men will be sent to kill him, Isobel agrees to help Kendig, mailing the first installment of his memoirs to spy chiefs in London, Paris, Rome, Moscow, Peking and, in a script mistake, to Washington, D.C. (CIA headquarters are in Langley, Virginia).

Kendig’s appointed replacement, Joe Cutter (Sam Waterston), isn’t concerned or amazed—he still likes the guy—when he receives a phone call, Kendig announcing his writing plans. The call is traced: he’s back in the U.S.; the number is Myerson’s Georgia home, which Kendig has somehow rented.

There, Kendig works on his next installment, drinking Myerson’s beer to the Mozart rondo and accompanied by a photo of his former boss, which magically has become angrier as the film progressed.

There, Kendig works on his next installment, drinking Myerson’s beer to the Mozart rondo and accompanied by a photo of his former boss, which magically has become angrier as the film progressed.

By the time Myerson’s men—now joined by the FBI—have surrounded the house and begun machine-gunning and tear-gassing the place, Kendig has already set spaced firecrackers on a long lighted fuse, to go off at random intervals. The chaos is accompanied on the soundtrack by “Un bel di” from Puccini’s Madame Butterfly—hardly a “fine day” for Myerson who screams for a cease fire, but, too bad, the FBI is now in charge.

Kendig has already slipped out of the house. From the bushes, he snatches Leonard Ross (David Matthau) as a hostage and, together, they speed away in an old pickup which Kendig had previously purchased and had specially adapted with two 55-gallon drums of motor oil. As the FBI and Myerson give chase in two cars, Kendig pulls a lever inside the cab, dumping the oil on the asphalt road and sending the cars skidding into a ditch. Kendig empties Ross’ gun and leaves him beside the road.

Kendig has already slipped out of the house. From the bushes, he snatches Leonard Ross (David Matthau) as a hostage and, together, they speed away in an old pickup which Kendig had previously purchased and had specially adapted with two 55-gallon drums of motor oil. As the FBI and Myerson give chase in two cars, Kendig pulls a lever inside the cab, dumping the oil on the asphalt road and sending the cars skidding into a ditch. Kendig empties Ross’ gun and leaves him beside the road.

Already armed with forged passports and bogus credit cards, Kendig meets lovely Carla (Lucy Saroyan), pilot of a float plane he has rented for a flight to Bermuda. From there to the U.K. where he buys a vintage 1930s biplane and presents an engineer with a schematic plan for some special device (unrevealed).

Now in London to submit to his publisher the final and most CIA-damning chapter of his memoirs, he leaves a cryptic message where he’ll be. Kendig’s pursuers, now including Yaskov, arrive in the hotel room, only to find their personal copies of the chapter and a recorded greeting. Before he departs, Kendig ties Cutter to a hotel chair and informs him that he’ll fly to Beachy Head, south of London on the English Channel.

Now in London to submit to his publisher the final and most CIA-damning chapter of his memoirs, he leaves a cryptic message where he’ll be. Kendig’s pursuers, now including Yaskov, arrive in the hotel room, only to find their personal copies of the chapter and a recorded greeting. Before he departs, Kendig ties Cutter to a hotel chair and informs him that he’ll fly to Beachy Head, south of London on the English Channel.

Arriving at Beachy Head in a helicopter and thinking they will head off their nuisance, the Americans and Yaskov see Kendig run toward the waiting biplane. The helicopter chases the airborne plane which suddenly explodes over the sea, against the chalk headlands of East Sussex (where, incidentally, on the South Downs, Sherlock Holmes plans to retire and keep bees). Myerson remarks that Kendig had “better stay dead.”

But with the imagination and cunning shown so far, is he dead? Hardly. He’s at a deserted building on an overgrown part of the airfield, nonchalantly depositing in a barrel of used engine oil the remote control—the results of that schematic plan—used to fly and destroy the biplane.

Isobel is nearby, waiting when he pulls up—in a stolen police car.

The supporting cast easily falls in with the jovial spirit of things—the heavily Southern-accented realtor (Jacquelyn Hyde), the border guard (Roland Froehlich), another Southerner (Severn Darden) who provides the sea plane and the mechanic (Randal Patrick) who modifies the pickup.

The supporting cast easily falls in with the jovial spirit of things—the heavily Southern-accented realtor (Jacquelyn Hyde), the border guard (Roland Froehlich), another Southerner (Severn Darden) who provides the sea plane and the mechanic (Randal Patrick) who modifies the pickup.

And Walter Matthau? In Hopscotch he’s the perfect, modern-day version of the Scarlet Pimpernel, though he never played the role. Maybe he should have! Planning ahead for all contingencies, Kendig is never once ruffled. Even, in the penultimate phase of his scheme, when it seems all might go awry, when his getaway car acquires a flat tire and police take him to their station so he can make a phone call and when one sergeant recognizes him from a wanted leaflet, he simply short-circuits an electrical socket with a paperclip and, in the confusion, steals a police car.

In the final scene, Kendig buys from a newsstand a copy of his memoirs, titled, naturally, Hopscotch, now an international bestseller. His disguise as a Sikh with a British accent annoys Isobel who feels he’s tempting discovery, now that the CIA, FBI and KGB think he’s dead. She nevertheless invites him for a game of gin rummy that night.

“For how much?” he asks.

“Will you never learn?” she replies.

And they walk off, arm in arm, accompanied by that Mozart rondo.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NX-TqWefqRQ [/embedyt]