“I’ll follow him around the Horn, and around the Norway maelstrom, and around perdition’s flames before I give him up.”—— Captain Ahab (Gregory Peck)

“At sea one day, you’ll smell land where there be no land. And on that day Ahab will go to his grave, but he’ll rise again within the hour. He will rise and beckon, then all—all save one—shall follow.” It was old Elijah who, from behind crates on the wharf, gives this warning to the sea novice Ishmael and the harpooner Queequeg not to sail on the “Pequod.”

The warning was not heeded by these characters, nor the other kind of warnings director [intlink id=”10″ type=”category”]John Huston[/intlink] experienced, whispered in the ear of his mind, growing more premonitory as filming progressed, regarding the difficulties in making his twelfth theatrical movie, Moby Dick. For one thing—just look at the cast!—there are no women, a hard package to sell anytime to Hollywood, especially in the 1950s. Following close behind as a deterrent, the film hadn’t a particularly action-filled plot. Oh, it was about this crazy man in pursuit of a Great White Whale, but beyond the climax, granted, an exciting, somewhat metaphysical showdown between man and beast, there wasn’t much else except a lot of sailor talk, a little philosophizing, a bit of Biblical moralizing and a good deal of narration.

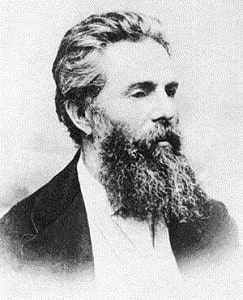

Which brings up another of Huston’s problems before the camera first rolled, and that was this colossus of a book, Herman Melville’s 1851 Moby-Dick—published with the hyphen—with all its stylized language, symbolism, anti-transcendental philosophy, a weightiness that compared with John Milton’s Paradise Lost. Both works have the somewhat similar thesis of good and evil, man’s struggle against the malevolent forces of the universe. Even Ahab, bearing the name of an evil king of the Old Testament, speaks in a Biblical vernacular, à la the King James version.

When John Huston wasn’t writing his own screenplays, he always had excellent co-writers, whether Christopher Fry (The Bible), Truman Capote (Beat the Devil), Richard Brooks (Key Largo), Arthur Miller (The Misfits) or Anthony Veiller (at least four Huston films, including The Night of the Iguana and Moulin Rouge).

When John Huston wasn’t writing his own screenplays, he always had excellent co-writers, whether Christopher Fry (The Bible), Truman Capote (Beat the Devil), Richard Brooks (Key Largo), Arthur Miller (The Misfits) or Anthony Veiller (at least four Huston films, including The Night of the Iguana and Moulin Rouge).

In Moby Dick, his co-writer was none other than Ray Bradbury. As Huston wrote in his autobiography, An Open Book, “I . . . saw something of Melville’s elusive quality in his work. . . . Highly original in his writing, from the idea itself to the very turn of a sentence, in casual intercourse Ray spoke entirely in clichés and platitudes.” When the science fiction writer joined Huston in Ireland for the collaboration, the director discovered Bradbury’s fear of riding in airplanes and in “fast” cars traveling over twenty m.p.h.

“Translating a work of this scope into a screenplay,” Huston summarized, “was a staggering proposition. Looking back now, I wonder if it is possible to do justice to Moby Dick on film.”

The next problem—in planning ahead, it had to be dealt with immediately—was the making of the models for the whale. Huston has written that there were three full-size, rather problematic “whales,” one which, he says, broke its towline and drifted into the open sea to become a shipping hazard. Another account, from the film’s cinematographer Oswald Morris, suggests there was never a full-sized model, only miniatures—if life-size, then only in parts, transported at sea on a barge, and used as needed. Otherwise, the interiors and whale close-ups were shot at Elstree Studios in England.

The next problem—in planning ahead, it had to be dealt with immediately—was the making of the models for the whale. Huston has written that there were three full-size, rather problematic “whales,” one which, he says, broke its towline and drifted into the open sea to become a shipping hazard. Another account, from the film’s cinematographer Oswald Morris, suggests there was never a full-sized model, only miniatures—if life-size, then only in parts, transported at sea on a barge, and used as needed. Otherwise, the interiors and whale close-ups were shot at Elstree Studios in England.

These “unbelievable misadventures,” as Huston called them, which rank with the difficulties of the director’s The African Queen, included a miscalculation in the costly dredging of the harbor at Youghal, near Cork City, Ireland, the stand-in for New Bedford. Huston wrote that the dredging for access by the “Pequod” was too shallow, meaning that “we could take the ‘Pequod’ in and out only at high tide—that is, during only about an hour a day.”

Ahab’s ship was modified from another vessel, with amateurish rigging and an added poop deck, but since the art of square-rigging had “gone with the past,” the lines were improperly and weakly rigged, resulting in two dismastings. And instead of placing the engines properly amidships, to save money Warner Bros. put them under the stern, so that the noise made it impossible to record dialogue.

(Note, here and later, the frequent quoting from the highly recommended An Open Book, a must-read for movie buffs, especially Huston aficionados.)

The plot is undoubtedly known, at least in its generalities, to practically everyone, although Philip Sainton, the British composer of the film’s score, admitted to being unfamiliar with the tome. The first line in the film is that of the book, one of the great openings in world literature—“Call me Ishmael.” It is spoken by this character (Richard Basehart), who narrates throughout the film.

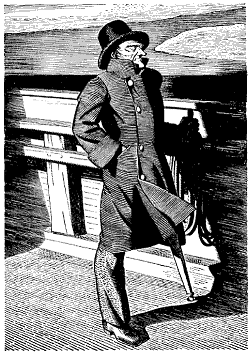

On a stormy night in 1841, Ishmael enters an inn filled with drinking, dancing, rowdy sailors. Stubb (Harry Andrews), second mate on the “Pequod,” praises the whale’s qualities and adds, “If God ever wanted to be a fish, he’d be a whale. Believe that, he’d be a whale.” At that moment, there are uneven footsteps from outside—plop, thud, plop, thud—and through the inn window is seen a tall man with a peg leg and a stovepipe hat. “That’s Ahab,” Stubb says, and when Ishmael asks who is Ahab, Stubb replies, “Captain Ahab to you. . . . Ahab’s Ahab.”

Ishmael, set on becoming a whaler himself, obtains a room for the night, unaware that his roommate is a former South Sea island cannibal, Queequeg (Friedrich Ledebur), with tattoos covering his whole body. Despite his fierce appearance, Queequeg is friendly and quickly makes a friend of Ishmael. After a sermon from Father Mapple (Orson Welles’ sole appearance), the two men sign up for passage on the “Pequod.” It was at this time that the two men are warned by Elijah (Royal Dano) not to sail on the vessel.

Ishmael, set on becoming a whaler himself, obtains a room for the night, unaware that his roommate is a former South Sea island cannibal, Queequeg (Friedrich Ledebur), with tattoos covering his whole body. Despite his fierce appearance, Queequeg is friendly and quickly makes a friend of Ishmael. After a sermon from Father Mapple (Orson Welles’ sole appearance), the two men sign up for passage on the “Pequod.” It was at this time that the two men are warned by Elijah (Royal Dano) not to sail on the vessel.

In a broad, vivid narration, Ishmael introduces the members of the crew, which maintains Melville’s cross section of humanity: the Quaker first mate Starbuck (Leo Genn); second mate Stubb, “carefree, foolish, laughing, wise Stubb”; ship’s carpenter (Noel Purcell, also in the 1962 Mutiny on the Bounty); the blacksmith (Ted Howard); the African native (Edric Connor) who “killed a lion with his bare hands and ate of its flesh”; the American Indian (Tom Clegg); the little black cabin boy Pip (Tamba Allenby); the Manxman (Bernard Miles, most famous for Joe Gargery in the 1946 Great Expectations); and other crew members played by Seamus Kelly and Mervyn Johns.

But where was Captain Ahab ([intlink id=”65″ type=”category”]Gregory Peck[/intlink])? Ishmael’s introduction of the crew is concluded with a shot of the closed doors of the great cabin. “Of our supreme lord and dictator, there was no sign. He stayed silently behind his locked door all the daylight hours.”

But where was Captain Ahab ([intlink id=”65″ type=”category”]Gregory Peck[/intlink])? Ishmael’s introduction of the crew is concluded with a shot of the closed doors of the great cabin. “Of our supreme lord and dictator, there was no sign. He stayed silently behind his locked door all the daylight hours.”

Ahab finally appears before the crew as some men are tarring the deck, in daunting aspect—not seen approaching, or emerging from a hatch or in some sort of panning shot up his body, but wholly there, in a sudden full-shot. Ishmael describes him: “Looming straight up and over us, like a solid iron figurehead suddenly thrust into our vision, stood Captain Ahab, his whole, high, broad form weighed down upon a barbaric white leg, carved from the jawbone of a whale. He did not feel the wind or smell the salt air; he only stood staring at the horizon, with the marks of some inner crucifixion and woe deep in his face.”

In the course of the film, before Ahab’s climactic combat with Moby Dick, there is the slaughter of one whale and the processing of its blubber for the oil that will “light the lamps of the world,” a kind of summary of the whaling process for the audience.

In the course of the film, before Ahab’s climactic combat with Moby Dick, there is the slaughter of one whale and the processing of its blubber for the oil that will “light the lamps of the world,” a kind of summary of the whaling process for the audience.

Later, a whole group (pod) of whales is sighted and harvesting begun, but when Captain Boomer (James Robertson Justice) of a passing ship comes aboard and casually mentions seeing a white whale, Ahab instantly abandons the hunt to go after his quarry. His pursuit is temporarily thwarted by a breezeless sea, and he directs that longboats pull the “Pequod” into a wind.