“Do you think because I’m poor and obscure and plain that I’m soulless and heartless? I have as much soul as you and fully as much heart.”—— Jane to Mr. Rochester

“Do you think because I’m poor and obscure and plain that I’m soulless and heartless? I have as much soul as you and fully as much heart.”—— Jane to Mr. Rochester

In the 1943 version of Jane Eyre, [intlink id=”259″ type=”category”]Joan Fontaine[/intlink] is playing yet another variation on her role of the new Mrs. de Winter in Rebecca, that of a demure woman with apparently little or no allure. “Mousy” might be the word. To some degree, in another Alfred Hitchcock film, Suspicion, she would have a similar part as a naïve woman growing more and more fearful that her husband might be planning to murder her. In both Jane Eyre and Rebecca, each women is haunted by a previous wife, one quite insane and alive, one dead.

Much like the nameless heroine in Rebecca, in Jane Eyre a second heroine and survivor against harsh odds, Jane comes to live in another mysterious old house in the English countryside, not as a new wife but at first as a governess. The secrets of the Cornish Manderley in Rebecca are replaced by those of a much more terrifying place, Thornfield Hall in Yorkshire. In the end, both houses suffer a conflagration, for the first a ritual cleansing, for the second a tender resolution. At Manderley, a dead wife holds a strange control over the living—worshipful for housekeeper Mrs. Danvers and suffocating for the master Maxim de Winter; at Thornfield, the wife is very much alive, at first unknown to Jane, and hidden away in a tower room, for good reason.

Jane Eyre is a dark film, darkly photographed by George Barnes (Meet John Doe, Rebecca, War of the Worlds [1953]), broodingly directed by Robert Stevenson and presided over, in ways not even now thoroughly understood, by what Fontaine called “such a big man in every way that no one could stand up to him.” [intlink id=”150″ type=”category”]Orson Welles[/intlink]. “On the first day,” she wrote in her autobiography No Bed of Roses, “at four o’clock”—having been many hours late—“he strode in followed by his agent, his secretary, his valet and a whole entourage. Approaching us, he proclaimed, ‘All right, everybody, turn to page eight.’ And we did it, though he was not the director.”

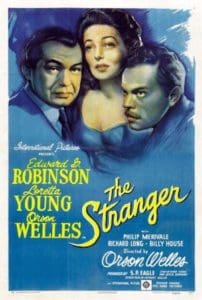

The screen-credited director, Englishman Stevenson, is best known for his Walt Disney films (Kidnapped, Son of Flubber, Mary Poppins) and the mogul’s TV series Wonderful World of Color. It has been said that in Jane Eyre Stevenson was able to avoid any directorial influences from the omnipresent Welles. But simply observing the screen, with its myriad shadows, deep focus images and the oppressive mood, as in The Stranger, which Welles did direct, it’s easy to doubt that Stevenson’s screen escaped untouched by Welles.

The screen-credited director, Englishman Stevenson, is best known for his Walt Disney films (Kidnapped, Son of Flubber, Mary Poppins) and the mogul’s TV series Wonderful World of Color. It has been said that in Jane Eyre Stevenson was able to avoid any directorial influences from the omnipresent Welles. But simply observing the screen, with its myriad shadows, deep focus images and the oppressive mood, as in The Stranger, which Welles did direct, it’s easy to doubt that Stevenson’s screen escaped untouched by Welles.

It is well known that Welles’ control was seriously restricted in another film of similar milieu, The Third Man, set a hundred years later. That director, Carol Reed, though clearly impressed by Orson, was a strong enough personality to maintain respectable control, even against an even stronger personality. Seen in retrospect, however, that film could easily be a teaching example of the Wellesian technique. Coincidence?

Charlotte Brontë’s 1847 novel, published under the pseudonym of Currer Bell, is in the style of the Gothic novel popular in England at the time. The youngest of the three Brontë sisters, she followed in the footsteps of other women novelists such as Elizabeth Gaskell and Fanny Burney who wrote about young ladies’ introduction to the cruel, male-dominated world of the Industrial Revolution. (Jane Austen, of an earlier generation and more a novelist of social manners, had died the year after Charlotte’s birth.) Young feminine hearts desired domination by a larger-than-life man—handsome, mysterious, even aloof, a man ready to introduce them to his new world. The basic ideas, allowing for women’s liberation, would persist in the romance novels of today.

But before any more introduction, the movie plot of Jane Eyre, should it be unknown to any one: Immediately establishing the gloom of the film, Jane Eyre (Peggy Ann Garner) is an independent and defiant orphan living at Gateshead Hall with her aunt, Mrs. Reed (Agnes Moorehead), and her spiteful son (Ronald Harris). Mrs. Reed finds Jane’s behavior untenable and arranges for her to be sent to an orphanage. As Jane is leaving for Lowood, the one kind person in the household, the maid Bessie (Sara Allgood), sees her to the door and gives her a token of remembrance.

But before any more introduction, the movie plot of Jane Eyre, should it be unknown to any one: Immediately establishing the gloom of the film, Jane Eyre (Peggy Ann Garner) is an independent and defiant orphan living at Gateshead Hall with her aunt, Mrs. Reed (Agnes Moorehead), and her spiteful son (Ronald Harris). Mrs. Reed finds Jane’s behavior untenable and arranges for her to be sent to an orphanage. As Jane is leaving for Lowood, the one kind person in the household, the maid Bessie (Sara Allgood), sees her to the door and gives her a token of remembrance.

For the coach ride to Lowood, composer Bernard Herrmann writes some exciting music, more inventive than a mere “galloping” rhythm, with ever-changing instrumentation. When the coachman (Charles Coleman) asks Jane where she is going and receives the answer, his silence and vacant look are telling. The distant shot of the coach, stopping at the gate of Jane’s new home and small beside the vast mountains in the distance, recalls Renfield’s arrival at the count’s castle in the 1931 scoreless version of Dracula. In Jane Eyre, in 1943, some dark, portentous music adds flavor to the setting and hints at Jane’s future.

Sounding like a name out of Charles Dickens, the man who runs Lowood is Henry Brocklehurst (Henry Daniell), an evil minister who abuses the children in his care. As there was kind Bessie at the Reed’s house, so at the orphanage there is the delicate Helen (the already lovely eleven-year-old Elizabeth Taylor, only a year from National Velvet). In defiance of Brocklehurst’s isolation of Jane, who has to stand, alone, on a stool “for the rest of the day” in a vast, empty room, Helen brings a piece of bread.

Sounding like a name out of Charles Dickens, the man who runs Lowood is Henry Brocklehurst (Henry Daniell), an evil minister who abuses the children in his care. As there was kind Bessie at the Reed’s house, so at the orphanage there is the delicate Helen (the already lovely eleven-year-old Elizabeth Taylor, only a year from National Velvet). In defiance of Brocklehurst’s isolation of Jane, who has to stand, alone, on a stool “for the rest of the day” in a vast, empty room, Helen brings a piece of bread.

Jane is also fortunate in the benevolent intercession of Dr. Rivers (John Sutton), who rescues her from another Brocklehurst punishment, walking in a circle in the rain carrying aloft two flatirons.

After Helen has died, Jane, now grown into a young woman (Fontaine), leaves the school for Thornfield Hall. She has been hired as governess to a little French girl, Adele (Margaret O’Brien), ward of a Mr. Edward Rochester (Welles). The housekeeper, Mrs. Fairfax (Edith Barrett), while showing Jane to her room, announces that the master of the house has been away sometime, and that his visits are always “unexpected and sudden.”

Later, as Jane is walking about the moors, out of the fog emerges a horseman and his Great Dane, almost running her down and throwing the rider to the ground—all supported by some arresting music from Herrmann. Without identifying himself, the man, wearing a great cloak, exchanges a few words, then remounts his animal and disappears in the fog, the large dog following behind. That evening, Jane discovers that the man on the moor, now sitting by the fire and at first hidden by a deep wing of the chair, is Mr. Rochester.

Later, as Jane is walking about the moors, out of the fog emerges a horseman and his Great Dane, almost running her down and throwing the rider to the ground—all supported by some arresting music from Herrmann. Without identifying himself, the man, wearing a great cloak, exchanges a few words, then remounts his animal and disappears in the fog, the large dog following behind. That evening, Jane discovers that the man on the moor, now sitting by the fire and at first hidden by a deep wing of the chair, is Mr. Rochester.

Jane quickly settles into the routine of the household, feeling affection for Adele and a growing closeness toward Mr. Rochester, despite his morose temperament. One night, Jane hears peculiar laughter and finds Mr. Rochester’s bed curtains on fire. The next day he leaves and is gone for many months.

When he does return, he heads a procession of coaches bringing guests for a wedding the next day—the master of the house to Blanche Ingram (Hillary Brooke). When Mr. Rochester accuses Blanche of planning to marry him for his wealth, she is indignant and leaves, whereupon he confesses to Jane that it is she he wants to marry. Jane gladly accepts his proposal.

When he does return, he heads a procession of coaches bringing guests for a wedding the next day—the master of the house to Blanche Ingram (Hillary Brooke). When Mr. Rochester accuses Blanche of planning to marry him for his wealth, she is indignant and leaves, whereupon he confesses to Jane that it is she he wants to marry. Jane gladly accepts his proposal.

But in the midst of the ceremony, an attorney (Erskine Stanford) announces that Mr. Rochester already has a wife named Bertha. When her elder brother (John Abbott) confirms this, Mr. Rochester stops the proceedings and shows the wedding party his spouse, locked away, insane, in the tower, watched over by Grace Poole (Edith Griffies). Distraught and heartbroken, Jane leaves Mr. Rochester and Thornfield.