What strange terror does the mask conceal?

Like Boris Karloff, Peter Lorre had an up-and-down career. Unlike the learned Englishman, who enjoyed cricket, had no drinking or drug problems and was, over-all, far more successful, even ending a long life “in the money” and on top professionally, Lorre was hooked on both drink and drugs from his earliest films and had what can only be called an unhappy, desultory life, dying at age fifty-nine.

The Austro-Hungarian achieved immediate fame in his second film, the German-made M, the story of a child-killer, directed by none other than Fritz Lang. Lorre made five more German films before, with the advent of Hitler, fleeing to France and a single, inconsequential film there, and then to Britain in 1934.

There he had the good fortune to meet Alfred Hitchcock. In many cases, rather than make a screen test, the director would audition a prospective actor by conducting a casual conversation, most often a monologue from Hitch, who delighted in story-telling.

Lorre had only the slightest comprehension of English and later recalled: “A friend of mine tipped me off that Hitch loved telling funny stories. So when he talked to me, I’d watch him very closely and whenever I guessed that he’d come to . . . what I thought was a joke, I would laugh uproariously. This made Hitch figure that I knew enough of the language to play the part, and that’s how I got the job.”

Lorre had only the slightest comprehension of English and later recalled: “A friend of mine tipped me off that Hitch loved telling funny stories. So when he talked to me, I’d watch him very closely and whenever I guessed that he’d come to . . . what I thought was a joke, I would laugh uproariously. This made Hitch figure that I knew enough of the language to play the part, and that’s how I got the job.”

In Hitch’s The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), Lorre’s first English-language film, he learned most of his lines phonetically and played, more than a little sinisterly, a sinister member of an espionage gang bent on kidnapping and political assassination. Despite resident British stars like Leslie Banks and Edna Best, Lorre was a key ingredient in the success of the movie.

Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1935), Lorre’s first American film, was directed by Josef von Sternberg—not an especially good film despite a number of the director’s signature touches, but it is yet another story about a murderer, which further contributed to the actor’s typecasting.

Lorre returned to England in 1936 for one last Hitchcock film, Secret Agent, an odd blend of comedy and thriller which doesn’t quite come off. Lorre would often disappear from the set to satisfy his drug habit.

Lorre returned to England in 1936 for one last Hitchcock film, Secret Agent, an odd blend of comedy and thriller which doesn’t quite come off. Lorre would often disappear from the set to satisfy his drug habit.

Then, in 1937, the actor began a series of eight Mr. Moto films for 20th Century-Fox. Strangely, the adventures of the never-failing Japanese detective competed with that studio’s own Chinese sleuth, Charlie Chan. At first, Lorre eagerly took to his new role, but by the time of the last film, Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation, in 1939, he was feeling, once again, typecast and his creative instincts limited. And, in retrospect, it was fortunate that Mr. Moto never returned from his vacation.

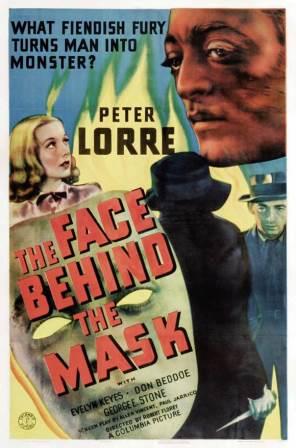

After five respectable film appearances during 1940, though clearly reflecting a career on hold, Lorre felt he had yet to find his proper niche. Then he made The Face Behind the Mask, his first film in 1941, which would prove to be a most prosperous, career-changing year—at least temporarily.

The low budget on this Columbia picture makes some of the sets look like ad hoc lean-tos in a dusty corner of a sound stage, with the carpenter’s materials temporarily removed. The film is made more impressive, however, by the tight direction of Robert Florey and the smooth cinematography of Franz Planer, who would, thirteen years later, photograph another Lorre film, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

The low budget on this Columbia picture makes some of the sets look like ad hoc lean-tos in a dusty corner of a sound stage, with the carpenter’s materials temporarily removed. The film is made more impressive, however, by the tight direction of Robert Florey and the smooth cinematography of Franz Planer, who would, thirteen years later, photograph another Lorre film, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

In The Face Behind the Mask, although he is essentially a villain once again, Lorre somehow handles with great subtlety at least three major changes in his character’s personality, changes due to fluctuating fortunes and his response to the various individuals he meets. He makes touching this story of a man whose face is disfigured in a fire and has to exist behind a mask, gaining a sizable degree of sympathy from the audience. The film is surprisingly good, an overlooked film noir and represents one of Lorre’s best performances.

In the opening, Janos “Johnny” Szabo (Lorre) is almost too happy an immigrant, optimistic and innocent, new to the U.S., on his first day in New York City. Learning a little English as he goes along, when he asks where he can find a “hot-and-cold-water hotel,” he takes literally a passing stranger’s comment that “they’re waiting for you” there.

Thinking he’s been “ganstered”—that his money has been stolen—he asks a kind policeman, James O’Hara (Don Deddoe), for help, only to find the money inside his shirt. “You have found my money!’ he exclaims. “Oh, American police is wonderful!” O’Hara takes him for an ice cream soda and recommends the Excelsior Palace, where it’s “clean, comfortable and cheap.” An unemployed watchmaker in a new country, Johnny luckily is hired as a dishwasher at the hotel café while he’s signing in for a room.

Thinking he’s been “ganstered”—that his money has been stolen—he asks a kind policeman, James O’Hara (Don Deddoe), for help, only to find the money inside his shirt. “You have found my money!’ he exclaims. “Oh, American police is wonderful!” O’Hara takes him for an ice cream soda and recommends the Excelsior Palace, where it’s “clean, comfortable and cheap.” An unemployed watchmaker in a new country, Johnny luckily is hired as a dishwasher at the hotel café while he’s signing in for a room.

That first night in his room he muses about his early good fortune, that he’ll soon be “rich,” soon able to bring his fiancée, Maria, from Hungary. During the night there’s a fire and Johnny is badly burned.

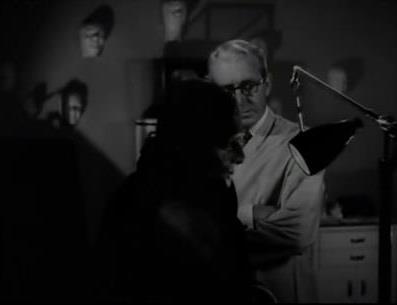

The unwrapping of his face bandages is dramatically handled, though it would become a cliché over time. The suspense builds as the doctor (Ben Taggart) says, “It’s a good thing the fire didn’t get your hands,” and slowly undoes the dressing. The shadows of the unraveling bandages fall across the nervous face of the nurse (Mary Currier), who, earlier, had covered a mirror with a towel. She closes her eyes and the stunned doctor drops the now loose bandages. Another nurse (Claire Rochelle) unexpectedly enters the room and screams.

“Why did she scream?” Johnny asks.

The viewer never sees his scared face until he pulls off the towel, and then only briefly in the mirror. He becomes hysterical, fighting with the doctor until he’s subdued by the nurse’s hypodermic needle. As he becomes unconscious, he murmurs, “Maria, Maria.”

The viewer never sees his scared face until he pulls off the towel, and then only briefly in the mirror. He becomes hysterical, fighting with the doctor until he’s subdued by the nurse’s hypodermic needle. As he becomes unconscious, he murmurs, “Maria, Maria.”

Looking for employment, he’s rejected by a watchmaker (Walter Soderling) and an aircraft factory personnel director (Harry Strang), the men repulsed by his face. Johnny writes to Maria that he’s found “a very pretty girl,” and signs the letter “forgive and forget.” Wandering the docks one night, without a job or money, he is contemplating suicide when a passerby (John Dilson) asks for a light and, seeing the face in the glow of the match, runs away, screaming.

(The music during these two or three previous scenes is especially effective, atmospheric and suspenseful. In fact, most of the score throughout the film is quite competent, belying its presence in a B movie. It is difficult, however, to determine who composed what. The only screen credit is for “musical director” Morris Stoloff, but the score is supposedly “by” Sidney Cutner. More a mishmash of stock footage, contributors include Dimitri Tiomkin and Mischa Bakaleinikoff, who worked for both Columbia and RKO as a music director.)

Moments later on the dock, a petty thief emerges from the shadows and shares with Johnny the money from the wallet the man had dropped. Unruffled by Szabo’s face, he introduces himself as Dinky (George E. Stone, best known as Chester Morris’ dim-witted sidekick in the Boston Blackie series of the 1940s). When Johnny almost faints from hunger, Dinky takes him to a cheap hotel, where they pay with money from the wallet.

Moments later on the dock, a petty thief emerges from the shadows and shares with Johnny the money from the wallet the man had dropped. Unruffled by Szabo’s face, he introduces himself as Dinky (George E. Stone, best known as Chester Morris’ dim-witted sidekick in the Boston Blackie series of the 1940s). When Johnny almost faints from hunger, Dinky takes him to a cheap hotel, where they pay with money from the wallet.

Dinky introduces his new-found friend to another criminal, Benson (Cy Schindell), who’s in charge pending the big boss’s return from prison. But Benson is soon displaced by Johnny, who overcomes the naïveté and natural honesty of that original immigrant.

Dinky encourages Johnny to acquire the money for a new face. ”You can buy a face?” Johnny exclaims. A physician’s assistant, Dr. Beckett (Edwin Stanley), makes him a temporary rubber mask for about $400, until Dr. Cheever (Frank Reicher), away on vacation, can rebuild his face, probably for several thousand dollars.

(For the “mask,” Lorre wears two strips of adhesive tape to immobilize part of his face and a layer of stark-white makeup by Ernie Parks. To further reinforce the illusion of a rubber mask, Lorre maintains a deadpan expression throughout the film. There is an impressive skull mask, but Lorre “puts it on” off-camera.)

(For the “mask,” Lorre wears two strips of adhesive tape to immobilize part of his face and a layer of stark-white makeup by Ernie Parks. To further reinforce the illusion of a rubber mask, Lorre maintains a deadpan expression throughout the film. There is an impressive skull mask, but Lorre “puts it on” off-camera.)

During a counting of the stolen receipts from an opera performance, when Johnny realizes he has enough money for his operation, the old boss, Jeff Jeffries (James Seay), enters the room. While coolly adjusting Jeffries’ tie, in a patient, yet threatening voice, Johnny suggests they can work together, be friends and that Jeff will receive a cut from the opera job, but Johnny will be boss. Jeffries sheepishly submits.

Johnny abandons the idea of a new face when Dr. Cheever tells him that it will take fifteen years, a little surgery at a time, before his face can be restored, and even then there is no guarantee.

As he is walking the sidewalk afterward, a young lady, Helen (Evelyn Keyes), carrying some packages, accidentally bumps into him. He is at first angry—the anger of the new boss of a criminal gang—and realizing she is blind, becomes contrite and apologetic—the quiet simplicity of that once newly arrived immigrant. He carries the packages to her apartment, and they begin seeing one another.

As he is walking the sidewalk afterward, a young lady, Helen (Evelyn Keyes), carrying some packages, accidentally bumps into him. He is at first angry—the anger of the new boss of a criminal gang—and realizing she is blind, becomes contrite and apologetic—the quiet simplicity of that once newly arrived immigrant. He carries the packages to her apartment, and they begin seeing one another.

(From a twenty-first century perspective, Keyes’ acting in The Face Behind the Mask may approach the sugary-sweet, just a bit too coy, but in the context of its time the performance was surely seen as touching and first-rate, as indeed it is.)

When another job presents itself, Johnny gives notice that he’s retiring from the gang and buys a house and a car for Helen and himself—and proposes marriage.

Jeffries mistakenly believes Johnny has double-crossed him with a police lieutenant, when an old business card from James O’Hara is found in Johnny’s desk. Jeffries finds Dinky and beats him into revealing where Johnny has gone. With Dinky no longer useful, the gang shoots him, but he staggers to a phone and warns Johnny that Jeffries has wired the radio of his new car to a bomb. Johnny arrives too late and Helen dies in his arms from the explosion. From a recuperating Dinky, Johnny learns that Jeffries and the gang are flying to Mexico.

Johnny disguises himself as the pilot. While over the Arizona desert, he lands the plane, saying they are out of gas and, being hundreds of miles from civilization, they will all die. In a letter, Johnny had asked O’Hara to meet him in the Arizona desert on a certain day, and when O’Hara and the police arrive, they find the four bodies of the gang. Johnny has died, strapped to one of the landing gears.

Johnny disguises himself as the pilot. While over the Arizona desert, he lands the plane, saying they are out of gas and, being hundreds of miles from civilization, they will all die. In a letter, Johnny had asked O’Hara to meet him in the Arizona desert on a certain day, and when O’Hara and the police arrive, they find the four bodies of the gang. Johnny has died, strapped to one of the landing gears.

On Johnny’s body, O’Hara finds a note addressed to him: “You remember the fire at the Excelsior Palace? You were kind to me. I never forgot. Those you find here were unkind. I did not forget them, either. [signed] Janos Szabo P.S. Here is the five dollars I owe you.”

Besides The Face Behind the Mask, in 1941 Peter Lorre made perhaps his best film, The Maltese Falcon, the milestone film noir detective story, with Humphrey Bogart, Mary Astor and Sydney Greenstreet.

This would be, significantly, the first of eight films Lorre and Greenstreet would make together between 1941 and 1946, excluding—please!—Hollywood Canteen. In some films, this unlikely duo, the fat man and the thin man, the garrulous and the creepy, would share many nefarious exploits, either as partners or as opponents, most notably in Three Strangers and The Verdict. Their best pairing was in The Mask of Dimitrios. In 1942 the two actors appeared in Casablanca, but, of course, Lorre was killed off early in the film.

This would be, significantly, the first of eight films Lorre and Greenstreet would make together between 1941 and 1946, excluding—please!—Hollywood Canteen. In some films, this unlikely duo, the fat man and the thin man, the garrulous and the creepy, would share many nefarious exploits, either as partners or as opponents, most notably in Three Strangers and The Verdict. Their best pairing was in The Mask of Dimitrios. In 1942 the two actors appeared in Casablanca, but, of course, Lorre was killed off early in the film.

In Warner Brothers’ only venture into the horror genre in the 1940s, director Robert Florey and Lorre were reunited for The Beast with Five Fingers (1946). Lorre plays a maniac who is choked to death by a wandering, disembodied hand—a ridiculous plot with an impressive, moody atmosphere. It would be his last film for the studio, as he once again returned to freelancing.

After turning mainly to television in 1952, ten years later he appeared in “The Black Cat” segment of Tales of Terror, the first of three horror films tenuously based on the tales of Edgar Allan Poe. Lorre was teamed with Vincent Price and Basil Rathbone, while in the two subsequent films, The Raven and The Comedy of Terrors, he was joined by Price and Boris Karloff.

After turning mainly to television in 1952, ten years later he appeared in “The Black Cat” segment of Tales of Terror, the first of three horror films tenuously based on the tales of Edgar Allan Poe. Lorre was teamed with Vincent Price and Basil Rathbone, while in the two subsequent films, The Raven and The Comedy of Terrors, he was joined by Price and Boris Karloff.

Finally, and sadly, Peter Lorre hit the bottom of the barrel in two 1964 embarrassments, Muscle Beach Party and The Patsy, a barrel shared by a number of respectable stars, including John Carradine and Jack Albertson, who should’ve known better. Lorre, who disowned The Patsy, died in 1964, four months before it premiered.