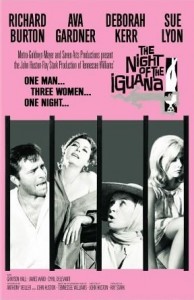

One man . . . three women . . . one night.

Although the flood has never slackened, the 1950s and the first half of the ’60s was the heyday of screen adaptations of Tennessee Williams’ plays and novels, an ideal source for the ever-growing sexual and language freedoms bursting from Hollywood at the time. Later revived endless times on Broadway, on theater screens and in TV movies, the first screen appearances of these plays, though often severely shorn of their initial impact, began, chronologically, with The Glass Menagerie, A Streetcar Named Desire, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Suddenly, Last Summer, Summer and Smoke and The Night of the Iguana.

More often than not, the plays concern a conflict, usually sexual, between a woman and a man, or a pair of women and men. At least one character is almost always weak, or otherwise disadvantaged in some way—physically, mentally or a victim of life’s unfairness. Most of the plays are downers, exposing the less admirable qualities in human beings, in keeping with Williams’ own defeatist view of life and the world.

Unlike most of these creations that are shrouded in a musty, decadent Southern milieu, Williams’ first official play, The Glass Menagerie, takes place in St. Louis. Geographically so close to the South, and with the color of the playwright’s literary brush, the play emerges thoroughly Southern in mood. The movie version (1950) was a fair transcription of the tensions among a lame girl (Jane Wyman), her faded, Southern belle mother (a rare screen appearance by Gertrude Lawrence) and a young suitor (Kirk Douglas). The somewhat languid pace of director Irving Rapper was avoided later in two superior adaptations—a 1973 TV movie (starring Katharine Hepburn) and a theatrical release in 1987 with Joanne Woodward, both ladies in the Lawrence role of Amanda Wingfield.

In A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), set in the French Quarter of New Orleans, the theme is the sexual friction among a man ([intlink id=”1583″ type=”category”]Marlon Brando[/intlink]) and his wife (Kim Hunter) and his neurotic sister-in-law ([intlink id=”124″ type=”category”]Vivien Leigh[/intlink]). So censored was the original release that in 1993 four minutes of explicit film were restored. Although Brando as the brutish Stanley Kowalski was the only one of the three Oscar-nominated stars who didn’t win, his performance endures as the most vivid, T-shirt and all, in perhaps the best film transference of any Williams play. Elia Kazan directed and Alex North wrote the pioneering jazz score.

In A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), set in the French Quarter of New Orleans, the theme is the sexual friction among a man ([intlink id=”1583″ type=”category”]Marlon Brando[/intlink]) and his wife (Kim Hunter) and his neurotic sister-in-law ([intlink id=”124″ type=”category”]Vivien Leigh[/intlink]). So censored was the original release that in 1993 four minutes of explicit film were restored. Although Brando as the brutish Stanley Kowalski was the only one of the three Oscar-nominated stars who didn’t win, his performance endures as the most vivid, T-shirt and all, in perhaps the best film transference of any Williams play. Elia Kazan directed and Alex North wrote the pioneering jazz score.

Even Williams’ less sexually dynamic characters have a vivid reality. In Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) the tussle between an alcoholic ex-footballer (Paul Newman) and his sex-starved wife ([intlink id=”1376″ type=”category”]Elizabeth Taylor[/intlink]) is eclipsed by the swaggering role of “Big Daddy” (Burl Ives). The Southern patriarch discovers he is dying of cancer, and while all vie for his favors, the alcoholic son, to his credit, will have none of it. The somewhat over-brilliant, sometimes gaudy color—not Technicolor but the studio processed Metrocolor—is a bit off-putting. It just seems appropriate that all Tennessee Williams plays should be filmed in black-and-white.

Even Williams’ less sexually dynamic characters have a vivid reality. In Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) the tussle between an alcoholic ex-footballer (Paul Newman) and his sex-starved wife ([intlink id=”1376″ type=”category”]Elizabeth Taylor[/intlink]) is eclipsed by the swaggering role of “Big Daddy” (Burl Ives). The Southern patriarch discovers he is dying of cancer, and while all vie for his favors, the alcoholic son, to his credit, will have none of it. The somewhat over-brilliant, sometimes gaudy color—not Technicolor but the studio processed Metrocolor—is a bit off-putting. It just seems appropriate that all Tennessee Williams plays should be filmed in black-and-white.

Suddenly, Last Summer (1959) seems to go beyond the usual sexual heat and tension, into the realm of the macabre, even Grand Guignol. Another Southern family head ([intlink id=”672″ type=”category”]Katherine Hepburn[/intlink]) attempts to persuade a neurosurgeon (Montgomery Clift) to perform a lobotomy on her niece (Elizabeth Taylor again) to prevent her from revealing the truth about her son’s homosexuality—so vaguely inferred here as to be indiscernible. Hepburn is reported to have been revolted by some of the dialogue she had to say. And those who have seen the film can not easily forget Hepburn’s introduction as Violet Venable coming down that elevator, nor her hothouse tropical garden with its Venus Flytrap.

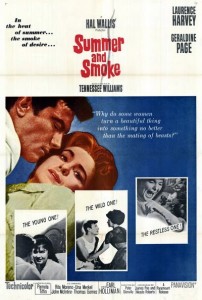

Summer and Smoke (1961)—set in 1916 Mississippi, Williams’ birthplace—is about a spinster (Geraldine Page), the personification of Southern gentility, who hankers after a young doctor (Laurence Harvey). The doctor isn’t interested, more turned on by a sultry local (Rita Moreno). The excellent supporting cast includes Thomas Gomez, Pamela Tiffin, John McIntire and Una Merkel. Not least of all is Elmer Bernstein’s subtle score, so subtle and so snugly moving beneath the dialogue that it can easily be overlooked, though not by the Oscar people, who nominated it. The music seems to capture the aroma of magnolias, the rustle of trees in the evening and the sense of that elusive smoke itself. In contrast with Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, the color here is soft-hued, perhaps to some degree desaturated, sharing those qualities with the score.

Summer and Smoke (1961)—set in 1916 Mississippi, Williams’ birthplace—is about a spinster (Geraldine Page), the personification of Southern gentility, who hankers after a young doctor (Laurence Harvey). The doctor isn’t interested, more turned on by a sultry local (Rita Moreno). The excellent supporting cast includes Thomas Gomez, Pamela Tiffin, John McIntire and Una Merkel. Not least of all is Elmer Bernstein’s subtle score, so subtle and so snugly moving beneath the dialogue that it can easily be overlooked, though not by the Oscar people, who nominated it. The music seems to capture the aroma of magnolias, the rustle of trees in the evening and the sense of that elusive smoke itself. In contrast with Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, the color here is soft-hued, perhaps to some degree desaturated, sharing those qualities with the score.

As The Glass Menagerie was Tennessee Williams’ first success, so The Night of the Iguana was his last great play, and one of the two or three greatest, period. Written mainly in Key West, Florida, with some tidying up in Italy, the play premiered at the Royale Theatre in New York, December 28, 1961. The reviews were mixed, but it is perhaps a Time magazine critic who hit upon the verdict that has held true to this day: “the wisest play [Williams] has ever written.”

In his biography of Williams’ life, The Kindness of Strangers, Donald Spoto, who has done an even more in-depth study of Alfred Hitchcock, wrote of these five plays: “ . . . these remain among the great literary and dramatic works of our time, and at least a few of the short stories . . . will perhaps be recognized as masterpieces of that genre.” I can only add, why the unfairly limiting “perhaps,” Mr. Spoto?! Was it not Christopher Hitchens who said that he believed “perhaps” was the most overused word in his writer’s vocabulary?

Director John Huston’s film version of The Night of the Iguana (1964)—the screenwriting shared with Anthony Veiller—made several changes in the original story of a defrocked Episcopal priest, the Reverend T. Lawrence Shannon (Richard Burton), who guides a group of teachers on a cut-rate bus tour of Mexico, which ends up in a rundown hotel. As Shannon says, a “tour of God’s world conducted by a minister of God.” The hotel owner is an old friend, Maxine Faulk ([intlink id=”277″ type=”category”]Ava Gardner[/intlink]), whose husband, “old Fred,” has died since Shannon’s last visit, and who uses two beach boys as stand-ins.

Director John Huston’s film version of The Night of the Iguana (1964)—the screenwriting shared with Anthony Veiller—made several changes in the original story of a defrocked Episcopal priest, the Reverend T. Lawrence Shannon (Richard Burton), who guides a group of teachers on a cut-rate bus tour of Mexico, which ends up in a rundown hotel. As Shannon says, a “tour of God’s world conducted by a minister of God.” The hotel owner is an old friend, Maxine Faulk ([intlink id=”277″ type=”category”]Ava Gardner[/intlink]), whose husband, “old Fred,” has died since Shannon’s last visit, and who uses two beach boys as stand-ins.

Before long, there arrives at the hotel an itinerant spinster artist, Hannah Jelkes ([intlink id=”492″ type=”category”]Deborah Kerr[/intlink]), and her grandfather, Nonno (Cyril Delevanti), “the world’s oldest living and practicing poet.” They cannot afford to pay for their room, but Maxine, under Shannon’s insistence, allows them one free night. Accompanying the tour, and in constant pursuit of the priest, who, anyway, seems to prefer the “young ones,” is an underage, sexually precocious nymph, Charlotte Goodall (Sue Lyon).

In the film’s longest scene, on a veranda during a threatening thunderstorm, Shannon and Hannah discuss the nature of God, sexual experiences and borderline insanity, and she compares his “spook” with her own “blue devil,” their individual versions of the demons that torment them. “And, oh,” she says, “we had quite a contest between us, this blue devil and I.”

In the film’s longest scene, on a veranda during a threatening thunderstorm, Shannon and Hannah discuss the nature of God, sexual experiences and borderline insanity, and she compares his “spook” with her own “blue devil,” their individual versions of the demons that torment them. “And, oh,” she says, “we had quite a contest between us, this blue devil and I.”

Part of this time Shannon is strapped in a hammock, after he attempted to “take the long swim to China.” When his terrors have subsided, she unties him. Together, they free another tied-up creature, an iguana which is awaiting fattening up before being eaten up. “We’ll play God tonight,” Shannon tells Hannah, “like kids play houses with old crates and boxes. We’ll cut the damn lizard loose so he can go back to his bushes, because God won’t do it and we’re playing God here tonight.”

Nonno, after finishing his poem, dies and Hannah leaves for the nearby village to resume her character sketching and a new life on her own. Maxine, saying she has had enough of the business, had earlier offered the hotel for Hannah and Shannon to run. The spinster had turned her down, but Shannon offers himself as a partner. Maxine suggests they go down to the beach for a swim. He says he can get down but doesn’t know if he can get back up. “Oh, I’ll get you back up, baby,” she says. “I’ll get you back up.”

Huston added a prologue before the main title: from the pulpit, Shannon curses his congregation. He feels their reproachful stares, imagines their whispers; they have heard of his sexual indiscretion with a parishioner. He chases them from the church—during a rainstorm, which will tie-in later with the threatening storm during the “lizard-freeing” scene. In another change, Huston moved the setting from Acapulco to about 500 miles north, up the western coast of Mexico to a then isolated and unknown Puerto Vallarta—and a hilltop hotel, especially built for the movie. The success and fame of Iguana turned Puerto Vallarta into a world-class resort. Also, Huston’s script eliminates the pro-Nazi visitors at the hotel and makes Maxine a softer character, the savior and companion for Shannon, not his destroyer.

Huston added a prologue before the main title: from the pulpit, Shannon curses his congregation. He feels their reproachful stares, imagines their whispers; they have heard of his sexual indiscretion with a parishioner. He chases them from the church—during a rainstorm, which will tie-in later with the threatening storm during the “lizard-freeing” scene. In another change, Huston moved the setting from Acapulco to about 500 miles north, up the western coast of Mexico to a then isolated and unknown Puerto Vallarta—and a hilltop hotel, especially built for the movie. The success and fame of Iguana turned Puerto Vallarta into a world-class resort. Also, Huston’s script eliminates the pro-Nazi visitors at the hotel and makes Maxine a softer character, the savior and companion for Shannon, not his destroyer.

As for the possible color vis-à-vis black-and-white dilemma, Huston and his co-producer, Ray Stark, discussed which way Iguana should be filmed. Stark wanted color, Huston black-and-white. “I thought the color—especially the sea, sky, jungle, flowers, birds, iguanas, beaches—would be distracting,” the director said in his autobiography, An Open Book. “Looking back now, I was probably wrong.” No, I believe the black-and-white is right.

Tennessee Williams often visited the set. Although he disapproved of Huston’s happy ending, he wrote an additional scene for Shannon and Charlotte. One night, she comes abruptly into his room. He is startled and knocks a bottle off the chest of drawers. He is so agitated—though weak, he does seem her victim but sincerely wants rid of her—he unknowingly walks on the glass from the broken bottle. Inspired by what she believes to be her love for him, and wanting to share the experience, Charlotte removes her sandals and joins him.

Tennessee Williams often visited the set. Although he disapproved of Huston’s happy ending, he wrote an additional scene for Shannon and Charlotte. One night, she comes abruptly into his room. He is startled and knocks a bottle off the chest of drawers. He is so agitated—though weak, he does seem her victim but sincerely wants rid of her—he unknowingly walks on the glass from the broken bottle. Inspired by what she believes to be her love for him, and wanting to share the experience, Charlotte removes her sandals and joins him.

Critics, especially movie critics, often complain that some of Tennessee Williams’ works for the stage are “talky.” Well, of course all plays are “talky,” since few deal with explosions, fewer still with car chases. Rather with words. Dialogue. Ideas. Opened up somewhat in the film beyond most of the activity at the hotel are a chase to catch an iguana, a threesome night beach scene, a cantina fight set to source music of a phonograph recording of “Mexican Hat Dance,” an ocean swim by Shannon and Charlotte, a wild bus ride and a stop on a bridge to observe, as Shannon says, “a fleeting glimpse into the lost world of innocence”—women washing clothes and children playing in a stream.

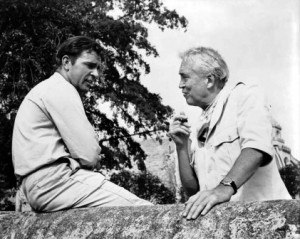

Speaking of that wild bus ride, at the American Film Institute’s Life Achievement Award ceremonies in 1983 honoring John Huston, among the many celebrities who lauded the director was Richard Burton. In relating his tenure at the wheel of that old, school-type 1950 International-Harvester bus, careening down a Mexican dirt road, a precipice to the right and luggage crashing from overhead, Burton quoted the director’s instructions, a perfect imitation of Huston’s measured, rolling, deep voice: “A little faster, Dick, a little faster.”

Speaking of that wild bus ride, at the American Film Institute’s Life Achievement Award ceremonies in 1983 honoring John Huston, among the many celebrities who lauded the director was Richard Burton. In relating his tenure at the wheel of that old, school-type 1950 International-Harvester bus, careening down a Mexican dirt road, a precipice to the right and luggage crashing from overhead, Burton quoted the director’s instructions, a perfect imitation of Huston’s measured, rolling, deep voice: “A little faster, Dick, a little faster.”

The humor is a vivid counterbalance to the general seriousness of the Iguana themes, little one-liners, some of them Williams’, some Huston’s, that shine like pearls among the less bright jewels of dialogue. The best comic moment is the intoxicated Shannon’s phone monologue to the big cheese of Blake’s Tours, with Maxine in the background, laughing and snickering. The speech deserves quoting, if only in part:

“A tour conductor is like the captain of a ship—once the bus leaves the terminal, he is in sole command. And let me assure you that Shannon runs a taut bus. . . . I have here in my pocket the symbol of my command, right here in my pocket. You cannot fire a man who has the distributor head.”

“A tour conductor is like the captain of a ship—once the bus leaves the terminal, he is in sole command. And let me assure you that Shannon runs a taut bus. . . . I have here in my pocket the symbol of my command, right here in my pocket. You cannot fire a man who has the distributor head.”

That same year, 1964, Burton was Oscar-nominated for a more theatrical performance, with delivery sometimes in the overly florid style of Laurence Olivier. The film was Becket, the role the archbishop of Canterbury to Henry II (Peter O’Toole). The Iguana acting, indeed, calls for a more nuanced delivery and a greater range—condemning outrage, sincere humility, frantic desperation, quiet guidance, drunken humor, suicidal panic. As for either of Burton’s performances, the point is moot. Both Burton’s and O’Toole’s nominations were voided by Rex Harrison’s win for My Fair Lady.

The nature of Kerr’s character—quietly resolute and always in control, with a touch of the virtuous and the wise—lays the foundation for one of her best performances. Within the context of Kerr’s long acting career that may not be much of a compliment: she always seems to give a “best performance” in each and every film. In Iguana, she is clearly worn down, though in annoyed restraint, by the maddening care of her grandfather. She is forever ready to calm his outbursts for a poem recitation and patiently listen to him recite, over and over, the beginning of his first new poem in twenty years. As she tells Shannon, “like a blind man climbing a staircase that leads nowhere.” Moments before Nonno dies, as she leaves him to retrieve his shawl, she hesitates in the semi-darkness, lifts her eyes upward and asks, “Oh, God, please, can’t we stop now?”

The nature of Kerr’s character—quietly resolute and always in control, with a touch of the virtuous and the wise—lays the foundation for one of her best performances. Within the context of Kerr’s long acting career that may not be much of a compliment: she always seems to give a “best performance” in each and every film. In Iguana, she is clearly worn down, though in annoyed restraint, by the maddening care of her grandfather. She is forever ready to calm his outbursts for a poem recitation and patiently listen to him recite, over and over, the beginning of his first new poem in twenty years. As she tells Shannon, “like a blind man climbing a staircase that leads nowhere.” Moments before Nonno dies, as she leaves him to retrieve his shawl, she hesitates in the semi-darkness, lifts her eyes upward and asks, “Oh, God, please, can’t we stop now?”

If Gardner sometimes goes overboard as the widow Faulk, it is in the grand Gardner manner. Still attractive at forty-two, with tasseled black hair and a staccato laugh, constantly animated, she always needed, as Huston relates in his autobiography, a push to counter her characteristic sense of inadequacy whenever tackling a new role.

If Gardner sometimes goes overboard as the widow Faulk, it is in the grand Gardner manner. Still attractive at forty-two, with tasseled black hair and a staccato laugh, constantly animated, she always needed, as Huston relates in his autobiography, a push to counter her characteristic sense of inadequacy whenever tackling a new role.

The only member of the cast nominated (unsuccessfully) for an Oscar, here in a supporting role, was Grayson Hall as the repressed lesbian attracted to Charlotte. As Shannon excused himself to Maxine from criticizing her, “Mrs. Fellowes is a highly moral person. If she ever recognized the truth about herself, it would destroy her.”

Aside from Mexican cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa’s steady and wonderfully non-artsy camera (also Oscar-nominated), Benjamin Frankel’s score deserves mention. Again, like Bernstein’s for Summer and Smoke, Frankel’s is understated. That wild bus ride is one of the few opportunities for an upfront, expansive display of his talents. The sense of misty damp, almost of a mystical primeval, that is established in the main title continues throughout the film. The orchestra is small, the textures and themes economical and uncomplicated, often chamber-like.

Even with at least seventy feature movies to his credit, Frankel is just another of many dimly remembered film composers. In Frankel’s case it is especially unfortunate. The music for Iguana is among his best. He also scored The Importance of Being Earnest (1952), Footsteps in the Fog and his magnum opus, Battle of the Bulge.

In London many years later, John Huston and Tennessee Williams met once again. After the usual pleasantries, as they were parting, Williams brought up their meetings in Puerto Vallarta during the filming of The Night of the Iguana. “I still don’t like the finish, John!” he said.