“I’m very lucky. I really had some wonderful movies.” ——Maureen O’Hara

Just which one movie to select to represent the career of Maureen O’Hara, who died October 24, 2015, age 95, is a conundrum—not that a single film is necessarily the ideal procedure; better, maybe, a sampling of some of her numerous fine screen appearances. As a single-film choice, however, what about perhaps her most popular, best-remembered, Miracle on 34th Street (1947)? Or her official introduction to the American public, in 1939, as Esmeralda in The Hunchback of Notre Dame? Or, even, that sentimental John Ford Oscar winner, How Green was My Valley (1941), its Irish zest fitting this Irish lass to the core? Any one of these is a tempting choice.

Coming closer to an ideal movie, more sentimental, more Irish than even Valley, also John Ford-directed, what about 1952’s The Quiet Man? And the film is with John Wayne. The magnetism between the two is unmistakable. O’Hara herself said of her frequent co-star: “I wish all actors could be more like Duke—and speaking as a person, it would be nice if all people could be as honest and as genuine as he is. This is a real man.”

And Wayne returned the compliment: “There’s only one woman who has been my friend over the years and by that I mean a real friend, like a man would be. [She’s] big, lusty and absolutely marvelous, definitely my kind of woman. She’s a great guy. I’ve had many friends and I prefer the company of men. Except for Maureen O’Hara.” Wayne pretty much summed up the woman, whether on screen or off—larger than life, independent and not one to take guff from anyone.

That she is one of the most beautiful stars in the movies is only one reason, in addition to those Wayne cited, for her thirty-five-year career. She is called the “Technicolor Queen,” partly because of her flaming red hair and because she made so many color films, this before color became the standard over B&W.

That she is one of the most beautiful stars in the movies is only one reason, in addition to those Wayne cited, for her thirty-five-year career. She is called the “Technicolor Queen,” partly because of her flaming red hair and because she made so many color films, this before color became the standard over B&W.

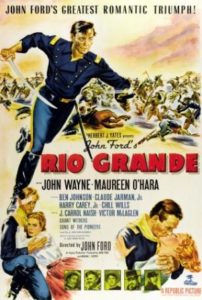

O’Hara and Wayne made five films together: the first, Rio Grande (1950), then The Quiet Man, The Wings of Eagles (1957), McLintock (1963) and their last, and poorest, Big Jake (1971). The first three are directed by Ford. The two stars did appear on stage in 1949, in What Price Glory, but by the time the movie came to be made, four years later, the leads had been replaced by James Cagney and Corinne Calvert, a poor remake of the 1926 Raoul Walsh silent film, despite Ford at the helm.

Scott Eyman, in his highly recommended and deliciously readable biography of John Ford, “Print the Legend”, aptly sums up the range of emotions in the kind of parts O’Hara and Wayne played together. Eyman thought the stars’ contribution to Ford’s movies important enough to mention as early as page six of his prologue: “ . . . in the trilogy of films Ford made with John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara, they evoked very nearly every phrase of mature heterosexual romance—courtship, raw sexual need, the compromises of marriage, the difficult rearing of children, catastrophic misalliance, and bitter estrangement.”

Scott Eyman, in his highly recommended and deliciously readable biography of John Ford, “Print the Legend”, aptly sums up the range of emotions in the kind of parts O’Hara and Wayne played together. Eyman thought the stars’ contribution to Ford’s movies important enough to mention as early as page six of his prologue: “ . . . in the trilogy of films Ford made with John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara, they evoked very nearly every phrase of mature heterosexual romance—courtship, raw sexual need, the compromises of marriage, the difficult rearing of children, catastrophic misalliance, and bitter estrangement.”

The Wayne/O’Hara film of choice, at least on this occasion, must be Rio Grande, not only because it is their first screen pairing, but because it reveals, mainly through unguarded expressions and glances, a more subtle and circumspect relationship than in most of their other movies together. Besides the strong love interest, at least in the film’s first half, there are some thrilling riding sequences, particularly Roman-style; what might be called some impressive “substitute” scenic vistas around Moah, Utah; and a superior orchestral score by Victor Young which underlines the already sweet sentimentality.

Also, Rio Grande deserves the additional exposure, being the most neglected, and least appreciated, of Ford’s cavalry trilogy, which includes Fort Apache (1948) and She Wore A Yellow Ribbon (1949). This is not to say, now, that Rio Grande is better than its two companions—it isn’t. The negatives include reduced action and a less interesting change of theme in the second half. The film being more studio-bound than its two companions only seems to accentuate the absence of Monument Valley, Ford’s trademark location for so many Westerns. For some, including this writer, the film contains too much singing by the Sons of the Pioneers. Ford loved any excuse to have vocalizing on the screen, and music was required accompaniment on his sets.

Also, Rio Grande deserves the additional exposure, being the most neglected, and least appreciated, of Ford’s cavalry trilogy, which includes Fort Apache (1948) and She Wore A Yellow Ribbon (1949). This is not to say, now, that Rio Grande is better than its two companions—it isn’t. The negatives include reduced action and a less interesting change of theme in the second half. The film being more studio-bound than its two companions only seems to accentuate the absence of Monument Valley, Ford’s trademark location for so many Westerns. For some, including this writer, the film contains too much singing by the Sons of the Pioneers. Ford loved any excuse to have vocalizing on the screen, and music was required accompaniment on his sets.

(A personal note: because The Horse Soldiers has a Civil War theme, rather than being a Western about Injun-fightin’, it has always been disqualified by critics from what could comprise Ford’s “cavalry quartet.” Underrated to start with, the film also stars Wayne and should be among the other three movies.)

In an impressive shot by cinematographer Bert Glennon, Rio Grande opens with the dusty return of Lt. Col. Kirby Yorke’s (Wayne) cavalry unit. The wounded are on travoises, pole litters dragged on the ground behind horses, while the captured Apaches ride with their arms tied behind their backs. Silhouetted in the foreground against the dust, the gathered women look anxiously for their men among the half-concealed horsemen. Glennon also photographed Cecil B. DeMille’s 1922 The Ten Commandments and Ford films including The Prisoner of Shark Island (1936), Young Mr. Lincoln, Stagecoach and Drums Along the Mohawk (all three 1939) and Sergeant Rutledge (1960).

In an impressive shot by cinematographer Bert Glennon, Rio Grande opens with the dusty return of Lt. Col. Kirby Yorke’s (Wayne) cavalry unit. The wounded are on travoises, pole litters dragged on the ground behind horses, while the captured Apaches ride with their arms tied behind their backs. Silhouetted in the foreground against the dust, the gathered women look anxiously for their men among the half-concealed horsemen. Glennon also photographed Cecil B. DeMille’s 1922 The Ten Commandments and Ford films including The Prisoner of Shark Island (1936), Young Mr. Lincoln, Stagecoach and Drums Along the Mohawk (all three 1939) and Sergeant Rutledge (1960).

Posted at a fort in Texas, Yorke is visited by Lt. Gen. Philip Sheridan (J. Carol Naish). It’s been fifteen years since they rode together down the Shenandoah Valley, meaning, though not said, since they laid waste every farm and crop they could find in their Civil War campaign of 1864. The two men discuss Yorke’s problem, a shortage of men, and their shared problem, the diplomatic inability of the cavalry to cross the Rio Grande after marauding Apaches.

Among a group of eighteen recruits comes Yorke’s son, trooper Jeff (Claude Jarman, Jr.), fresh from having failed at West Point. The colonel, in an effort to avoid showing any favoritism toward his son, becomes overly harsh toward him. At the same time, he allows a fight between Jeff and another soldier to continue rather than stop it and appear over-protective.

Among a group of eighteen recruits comes Yorke’s son, trooper Jeff (Claude Jarman, Jr.), fresh from having failed at West Point. The colonel, in an effort to avoid showing any favoritism toward his son, becomes overly harsh toward him. At the same time, he allows a fight between Jeff and another soldier to continue rather than stop it and appear over-protective.

Jeff, however, shows his mettle and, beyond any sympathy from his father, earns the respect of two fellow recruits, Daniel (Harry Carey, Jr.) and Travis (Ben Johnson), when Sgt. Maj. Quincannon (Victor McLaglen) orders the three to ride “like the ancient Romans,” that is, ride standing up, with a foot on each of two horses galloping abreast. Daniel and Travis have difficulty, but Jeff does it, amazingly, the first time and impresses all.

(It was, of course, John Ford who wrote this ride into the script and, three weeks before filming began, ordered the three men to learn to do it. Johnson gave excuses, that it might take longer to train the horses, and when Jarman, who had made a number of Westerns, did it after ten minutes, Johnson was a little more than irritated. One can wonder why Ford risked his actors in such a dangerous stunt. What are extras for? And, to defeat the logic of having his stars do it, Ford shot the sequence in long shots, so the audience assumes the riders were, after all, stuntmen.)

(It was, of course, John Ford who wrote this ride into the script and, three weeks before filming began, ordered the three men to learn to do it. Johnson gave excuses, that it might take longer to train the horses, and when Jarman, who had made a number of Westerns, did it after ten minutes, Johnson was a little more than irritated. One can wonder why Ford risked his actors in such a dangerous stunt. What are extras for? And, to defeat the logic of having his stars do it, Ford shot the sequence in long shots, so the audience assumes the riders were, after all, stuntmen.)

Yorke’s participation in the Shenandoah campaign becomes a fresh reminder when his estranged wife, Kathleen (O’Hara), arrives. It was both Yorke and Quincannon who had put the torch to Kathleen’s plantation. She has come to take her boy home, armed with the required $100. Father and son both resist her idea. Jeff reminds her that his signature, as well as his father’s, is required on any discharge request.

Kathleen and Kirby’s reunion is charged with tension, but also with an underlining sense of memories of what they had once meant to one another. Especially in her eyes and body language she seems to desire a reconciliation and even a renewal of her true feelings. When alone, she opens a music box and hears what must be their song, “I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen.”

After a quiet dinner together, the two are serenaded by the Sons of the Pioneers singing, coincidentally in movie fashion, the tune from the music box. Ken Curtis, another Ford regular—the film is, of course, filled with them—sings the solo; he would later play Festus on TV’s Gunsmoke. Kathleen is clearly moved by the moment and looks longingly at Kirby, but turns away when his eyes meet hers.

After a quiet dinner together, the two are serenaded by the Sons of the Pioneers singing, coincidentally in movie fashion, the tune from the music box. Ken Curtis, another Ford regular—the film is, of course, filled with them—sings the solo; he would later play Festus on TV’s Gunsmoke. Kathleen is clearly moved by the moment and looks longingly at Kirby, but turns away when his eyes meet hers.

(Ford didn’t really want to use the then famous singing group, unable to integrate them into the film since they weren’t actors and didn’t look like cavalrymen despite the daily application of dust which the director required to make his actors appear as veteran, trail-weary horse soldiers.)

The film now digresses from this already interesting dual theme of Yorke’s quite different relations with son and wife and the prospects for further development, and becomes more obviously a John Ford Western. What, after all, is the cavalry for if not to chase, fight and kill Indians?

General Sheridan returns. He and Yorke discuss, as they had before, the Shenandoah and the bad coffee, only now, tired of diplomatic tiptoeing and willing to violate the invasion of a sovereign nation, Sheridan authorizes Yorke’s unit to cross the Rio Grande into Mexico in pursuit of the Apaches. Despite the threat of court-martial if he fails in his mission, the general assures him that sympathetic men “who rode down the Shenandoah” will be his judges.

General Sheridan returns. He and Yorke discuss, as they had before, the Shenandoah and the bad coffee, only now, tired of diplomatic tiptoeing and willing to violate the invasion of a sovereign nation, Sheridan authorizes Yorke’s unit to cross the Rio Grande into Mexico in pursuit of the Apaches. Despite the threat of court-martial if he fails in his mission, the general assures him that sympathetic men “who rode down the Shenandoah” will be his judges.

On the way to Mexico, however, Yorke learns that a group of children en route from the fort to Fort Bliss for safety have been taken by the Indians. In what proves to be a victorious attack and the rescue of the children, Yorke is struck in the chest with an arrow. Jeff removes it, earning, finally, his father’s full acceptance and affections.

The story comes full circle. As Rio Grande had opened, now it’s Yorke who is on a travois, entering the fort with his cavalry. Among the women who come this time to meet their men is Kathleen, who takes her husband’s hand and walks alongside his litter.

The story comes full circle. As Rio Grande had opened, now it’s Yorke who is on a travois, entering the fort with his cavalry. Among the women who come this time to meet their men is Kathleen, who takes her husband’s hand and walks alongside his litter.

Following Yorke’s recovery, Jeff, Daniel and Travis are among those receiving metals, and the troops pass in review before General Sheridan. Young’s score contains a rousing rendition of “Dixie,” as if to underline that, though Kathleen might not have forgotten the burning of her home, she and Kirby have decided to give their marriage another try.

Maureen O’Hara labeled John Ford “a bitterly disappointed man,” because, she suggested, he either wanted to be “back in Ireland or a military hero”—he was in World War II as a documentary photographer. O’Hara couldn’t understand, she added, why he had hit her on a set on one occasion, without ever apologizing.

Most people who knew John Ford have generally agreed that, though he was an angry, even mean man, buried—and buried deep, yes—inside his psyche was a kind, sentimental side which he rarely revealed. He directed for almost sixty years—back to the silents of 1914—and his behavior was tolerated because he made so many great movies and knew more about film-making than just about anyone—and he knew good actors when he saw them.

Most people who knew John Ford have generally agreed that, though he was an angry, even mean man, buried—and buried deep, yes—inside his psyche was a kind, sentimental side which he rarely revealed. He directed for almost sixty years—back to the silents of 1914—and his behavior was tolerated because he made so many great movies and knew more about film-making than just about anyone—and he knew good actors when he saw them.

He would even occasionally compliment them, if begrudgingly, as he did Maureen O’Hara: “She is a woman who speaks her mind and that impressed me, despite my old-fashioned chauvinistic ways! She is feminine and beautiful, but there is something about her that makes her more like a man. It’s her stubbornness and her willingness to stand up to anyone.”