“I knew what I was going to do yesterday and the day before that . . . right back to the first time you both met. . . . You see, I decided what to do with the next one, before you even met my wife. And you, Bill, are ‘the next one.’ . . . I’ve going to kill you.”— Dr. Clive Riordan

“I knew what I was going to do yesterday and the day before that . . . right back to the first time you both met. . . . You see, I decided what to do with the next one, before you even met my wife. And you, Bill, are ‘the next one.’ . . . I’ve going to kill you.”— Dr. Clive Riordan

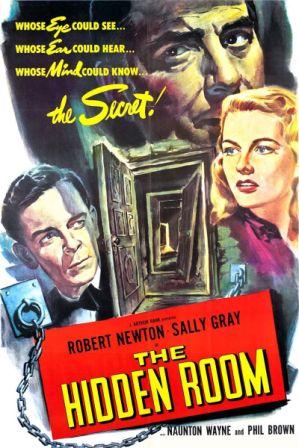

Later changed to Obsession, the original title, The Hidden Room, is by far the more accurate of the two. Most of the characters, even the seemingly innocuous detective, are either lying, laying a scent of deception or simply other than what they purport to be. The crux of the plot is actually two hidden rooms, one just beyond reach of a prisoner and the larger room in which he is chained to a wall.

The larger room has two bathrooms, each with a tub, which is a key element in the plot—one bathroom for the prisoner’s convenience, the other for diabolical use by one who is planning murder.

The Hidden Room has a lot going for it, a forgotten treasure which needs to be seen and appreciated. Despite it’s ambling, typically British pace, it’s so well directed—by Edward Dmytryk, who fled to England after being blacklisted in the U.S.—and photographed—by C.M. Pennington-Richards, who would shoot Alistair Sim’s Christmas Carol in 1951—that the leisurely tempo becomes an asset.

All the more time to absorb the subtleties of the erudite dialogue by Alec Coppel, later screenwriter for Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo. Save for one American, Phil Brown, the all-British cast is headed by, best of all, Robert Newton. Sophisticated, patient and always civilized, never raising that voice with its cultured, rolling tones, Newton is so good as the villain—and that’s revealed rather soon—that it’s hard not to root for him.

After a drink at his men’s club, Dr. Clive Riordan (Newton), a respected London psychiatrist, returns home to find his wife Storm (Sally Gray) entertaining a young American, Bill Kronin (Brown). Storm says it was all most innocent, that they had been to a concert. Responding to Clive’s seemingly interested questions, the couple say they enjoyed the concert, but turn a shared shade of white when Clive announces—always with drawing room civility—that the concert was cancelled.

Where have they been, then? Clive asks. Why, to the Savoy for something to eat—“no dancing,” Sally assures him. Clive then admits to lying, that there was a concert. He telephones the Savoy and learns his wife and her American friend were not there either.

Where have they been, then? Clive asks. Why, to the Savoy for something to eat—“no dancing,” Sally assures him. Clive then admits to lying, that there was a concert. He telephones the Savoy and learns his wife and her American friend were not there either.

At gunpoint, Clive calmly declares that for a long time he’s tolerated his wife’s dalliances, that “There have been so many harmless little flirtations.” He tells Bill he’s the last, that he’s going to kill him.

Unseen by any one, Clive forces Bill to the garage where the psychiatrist keeps his car and has a lab, and, beyond, to the ruins of a deserted bombed out building (that soon after the German Blitz much such rubble was still extant in 1949 London) to a room with a bed, a table and two bathrooms. Chained to the wall, Bill cannot move more than ten feet or so from his bed, his boundary marked by white tape on the floor.

“See if you can work it out for yourself,” Clive tells him, “—why I’m keeping you a prisoner instead of killing you right away.”

“See if you can work it out for yourself,” Clive tells him, “—why I’m keeping you a prisoner instead of killing you right away.”

Unexpectedly, the Riordan’s family dog Monty follows Clive’s scent to the hideout. With Monty a security risk, Clive sees a chance to test his concoction and attempts to throw the animal in the tub. But Bill grabs the dog and Clive is reluctant to enter the circle where his prisoner can attack him. Bill puts Monty on his own tether.

After many visits, Clive prepares for Bill’s final day, giving him a drug-laced martini. But during his time alone, the prisoner had trained Monty to pull the chain-attached stopper in his tub, and Clive finds “his” tub drained of its liquid.

Meanwhile, pipe-smoking Scotland Yard Superintendent Finsbury (Naunton Wayne), impassive and affable, Columbo-style, has been popping up, even interrupting Clive’s time with his model trains.

Finsbury arrives at the house after Sally has called on “a matter of life and death.” Unruffled, he tells her Bill must still be alive for Clive has been seeing him—otherwise why have Americanisms crept into the psychiatrist’s normally proper British speech. Finsbury puts out a general call for Clive’s car.

A London bobby finds it in Clive’s garage and the unconscious Bill is rescued. Clive escapes from his lab and returns to his club where he calmly waits for Finsbury. Clive admits that his plan for the perfect murder had become an obsession—the first time the word is mentioned in the movie. “I forget,” he asks. “What’s the penalty for a near miss?”

A London bobby finds it in Clive’s garage and the unconscious Bill is rescued. Clive escapes from his lab and returns to his club where he calmly waits for Finsbury. Clive admits that his plan for the perfect murder had become an obsession—the first time the word is mentioned in the movie. “I forget,” he asks. “What’s the penalty for a near miss?”

Bill is recovering in the hospital when Sally arrives with Monty, saying she is off on a cruise toSouth America. For her, Bill has been, as Clive had said, just another “harmless little flirtation.” Nor does he seem much disappointed, especially when Monty breaks away from Sally and hops on his bed.

The most important reason to see The Hidden Room is to watch and behold Robert Newton. He earned a certain notoriety as the movie pirate, setting the standard for what all unrespectable pirates should be, first as Long John Silver in Walt Disney’s Treasure Island (1950), then as Blackbeard in Blackbeard the Pirate (1952).

This screen image generally ruined his career, that and, foremost, drink. Even in Around the World in 80 Days in 1956, the year of his death, the pirate mannerisms of those rolling eyes and cocked head had surfaced in his role as Inspector Fix. He had begun promisingly in the original Gaslight (1940), as Lukey in Odd Man Out (1947), Bill Sykes in Oliver Twist (1948) and surely as Clive Riordan in The Hidden Room.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5wBwI2V4k4k[/embedyt]