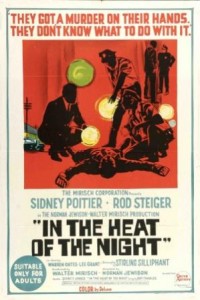

They got a murder on their hands. They don’t know what to do with it.

The most famous line from In the Heat of the Night, “They call me MISTER Tibbs!,” is not, by any means, the best line. There are several. For instance: “I got the motive, which is money, and the body, which is dead.” Another better one: “There’s white time in jail and there’s colored time in jail. The worst kind of time you can do is colored time.” Finally: “I want that officer given a free hand, otherwise I will pack up my husband’s engineers and leave you . . . to yourselves.”

The three lines are spoken by three different characters. The first by the local police chief, Bill Gillespie (Rod Steiger), the second by a “passing through” Philadelphia homicide expert, Virgil Tibbs (Sidney Poitier), and the last by Leslie Colbert (Lee Grant), the recent widow of a wealthy industrialist who came to this impoverished Southern town to build a factory.

The famous “MISTER Tibbs” line, which director Norman Jewison admits is over the top, provided the title for the first of two sequels featuring Poitier as Tibbs, the other being The Organization. Neither follow-up, especially the first, equaled the quality of the original. The story was reincarnated in a 1988-95 TV series starring Carroll O’Connor as Gillespie and Howard E. Rollins, Jr. as Tibbs.

Out of the racial strife of the 1960s, In the Heat of the Night, more so than most related films of the era, has remained relevant and aged none at all, though the racial inequality at the heart of the movie still has not been completely resolved in the United States. More than its timeliness, the key ingredient in the film’s durability, certainly its watchability, is the chemistry between Poitier and Steiger, each giving perhaps the best performance of his career.

Steiger won a Best Actor Oscar. Strangely Poitier wasn’t nominated, though 1967 was also the year of his Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner success, a totally different, if conventional role. In fact, In the Heat of the Night was voted Best Picture by the Academy. Stirling Sillphant won for Adapted Screenplay, Hal Ashby for Film Editing and the Samuel Goldwyn Studio for Sound. Unrewarded nominations include for Sound Effects and Jewison for Direction (the winner was Mike Nichols for The Graduate).

Steiger won a Best Actor Oscar. Strangely Poitier wasn’t nominated, though 1967 was also the year of his Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner success, a totally different, if conventional role. In fact, In the Heat of the Night was voted Best Picture by the Academy. Stirling Sillphant won for Adapted Screenplay, Hal Ashby for Film Editing and the Samuel Goldwyn Studio for Sound. Unrewarded nominations include for Sound Effects and Jewison for Direction (the winner was Mike Nichols for The Graduate).

Perhaps because Haskell Wexler had won in the black and white category the previous year for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, he was not nominated for Best Cinematography for In the Heat of the Night. (Beginning in 1967, no distinction would be made between black and white and color photography, a dual classification which had begun in 1939.)

Perhaps because Haskell Wexler had won in the black and white category the previous year for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, he was not nominated for Best Cinematography for In the Heat of the Night. (Beginning in 1967, no distinction would be made between black and white and color photography, a dual classification which had begun in 1939.)

Coincidentally, Beah Richards, who plays Mama Caleba, a source in this Southern town for abortions at a price, was nominated for Best Supporting Actress in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (Estelle Parsons won for Bonnie and Clyde).

Although In the Heat of the Night is set in Sparta, Mississippi, it was filmed mostly in Sparta, Illinois—for one reason, to save having to change the city’s signs; for another, Sidney Poitier did not wish to go south of the Mason-Dixon Line.

Although In the Heat of the Night is set in Sparta, Mississippi, it was filmed mostly in Sparta, Illinois—for one reason, to save having to change the city’s signs; for another, Sidney Poitier did not wish to go south of the Mason-Dixon Line.

At the same time a night patrolman, Sam Wood (Warren Oates), is finding a bludgeoned murder victim, a passenger (Poitier) is arriving at the train station. (In the first of numerous visual mistakes, one shot of the arriving passenger train is of a freight train.) Because the traveler is black and a stranger—more because he is black—Wood arrests him and brings him before police chief Gillespie.

The chief soon discovers that the falsely arrested black man is an expert homicide detective returning to his home and work in Philadelphia. Gillespie enlists his reluctant help, first in inspecting the body and then in staying to investigate. After many personal humiliations and a physical attack, Tibbs identifies the murderer despite a few wrong turns by both detectives.

Along the way, Gillespie never for a moment seems dumb or weak despite his Southern boorishness, his constantly chewing gum, his countrified speech. Beneath it all, he has more than a smattering of character. On petty things, he tolerates dilatory subordinates who fail to fix a window air conditioner and a faulty office gate, both running jokes in the film. On matters of integrity, he is visibly disgusted when the mayor (skillfully played by William Schallert) suggests that Tibbs can take the blame if the case doesn’t work out in the chief’s favor.

Despite the almost constant animosity between the two policemen, it’s evident that Gillespie has, first, a gnawing tolerance, later a respect, for Virgil Tibbs. Gillespie is a patient man as well. Although he shames Tibbs into staying as he is about to catch the next train North—“You’re just gonna stay here and show us all.”—he gives Tibbs more time when he does an about-face and wants to stay and solve the case. Gillespie is also concerned for Tibbs, that he leaves town when he is threatened in an abandoned railroad repair shop by “four maniacs,” as Gillespie calls them.

After Tibbs has returned the slap of cotton baron Eric Endicott (Larry Gates), Endicott asks Gillespie what he’s going to do about it. The bewildered chief stammers, “I don’t know.” Later, the mayor notes that any other police chief would have shot the black man on the spot, again disgusting Gillespie. In the Deep South in 1966—the date on Gillespie’s office calendar—lynchings of African-Americans still occurred.

After Tibbs has returned the slap of cotton baron Eric Endicott (Larry Gates), Endicott asks Gillespie what he’s going to do about it. The bewildered chief stammers, “I don’t know.” Later, the mayor notes that any other police chief would have shot the black man on the spot, again disgusting Gillespie. In the Deep South in 1966—the date on Gillespie’s office calendar—lynchings of African-Americans still occurred.

Moments later, as the two men leave Endicott’s mansion, Tibbs declares, “I can pull that fat cat down! I can bring him right off this hill!” Gillespie pauses, looks at him across the roof of the police car and observes, “Man, you’re just like the rest of us, ain’t you?” Another excellent line and one more exposure of Tibbs’ own prejudice.

While Virgil Tibbs does have his own quota of prejudice, he finds a sizable amount of it among the Sparta populace. Mrs. Colbert is the first in the film to see what the town folk have yet to notice about themselves, so accepting are they of their way of life. She speaks out when she witnesses Gillespie and Tibbs fighting over some evidence. “What kind of place is this? What kind of people are you?”

Besides the supporting cast already mentioned, the other players are equally well cast and exist in their own eccentric Southern milieu. Scott Wilson, in an astonishingly effective screen début, is the wrongly arrested pool player who uses a cheeseburger with onions as a bribe when Tibbs asks where a guy goes to set up an abortion. Regarding that A/C repair, Peter Whitney is the prototype pass-the-buck desk policeman. In several scenes, Wood is teased by Anthony James, the diner attendant who hides the officer’s favorite pies.

Quentin Dean, the local slut who parades in the nude before her window, fascinates more than just policeman Wood, who includes her house on his nightly rounds. James Patterson is Dean’s bigoted ugly brother. Even Kermit Murdock shines in his only scene as the slow-talking bank president. Upon Gillespie’s prodding, the man discovers a $632 deposit and dryly observes, “That must’ve been when I was out to lunch. A deposit that size I’d remember.”

Quentin Dean, the local slut who parades in the nude before her window, fascinates more than just policeman Wood, who includes her house on his nightly rounds. James Patterson is Dean’s bigoted ugly brother. Even Kermit Murdock shines in his only scene as the slow-talking bank president. Upon Gillespie’s prodding, the man discovers a $632 deposit and dryly observes, “That must’ve been when I was out to lunch. A deposit that size I’d remember.”

Which conveys the serious amount of humor in the film.

The score is by Quincy Jones. Ray Charles sings Jones’ title song, with lyrics by Alan and Marilyn Bergman. Like all the music, it fits the sultry atmosphere, the tension and misery, of this forlorn Southern town. The menacing, repeated two-note motif heard several times during violent moments suggests the possible inspiration, eight years later, for John Williams’ shark theme in Jaws.

Besides being a top-notch, sophisticated mystery, In the Heat of the Night is a film about friendship. The two men’s hostility gradually softens—maybe “softens” is too strong a word for these two—into valued co-operation, even friendship. Perhaps more so on Gillespie’s part.

In a moving lull just before the dénouement, Gillespie senses a kindred spirit in Tibbs and invites him into his shabby house. “You know, Virgil,” he says, “you are among the chosen few—the first human being who’s ever been in here. . . . I’ll tell you a secret: nobody comes here—ever.” (The discrepancy in the line, i.e., “among”/“first,” is because the two actors ad-libbed this scene.) Gillespie seems to bare his soul and asks, “Don’t you get just . . . a little lonely?” Tibbs replies, “No lonelier than you, man.” Whereupon Gillespie balks: he doesn’t want any pity. “No thank you.”

This scene is one of the best in the film, and it definitely belongs to Steiger.

The case is solved. The murderer turns out not to be Endicott. Tibbs was wrong there, saying he was hung up on him for personal reasons. The killer of Mr. Colbert is, in fact, one of the first characters to appear in the film.

Gillespie drives Tibbs to the train station, making a point to carry the suitcase. “Gotcha ticket?” he asks. He passes the suitcase to Tibbs and flatly says, “Thank you,” shakes his hand and adds, just as detached, “Bye-bye,” before starting back toward the police car. Tibbs steps up to board the train. Gillespie turns back. “Virgil—” Tibbs glares, almost ready to pounce, it seems. “You take care,” Gillespie continues, “—ya hear?” Tibbs half smiles. “Yeah.” And climbs aboard. Gillespie exhibits a joyous smile as he chomps on that gum.

Gillespie drives Tibbs to the train station, making a point to carry the suitcase. “Gotcha ticket?” he asks. He passes the suitcase to Tibbs and flatly says, “Thank you,” shakes his hand and adds, just as detached, “Bye-bye,” before starting back toward the police car. Tibbs steps up to board the train. Gillespie turns back. “Virgil—” Tibbs glares, almost ready to pounce, it seems. “You take care,” Gillespie continues, “—ya hear?” Tibbs half smiles. “Yeah.” And climbs aboard. Gillespie exhibits a joyous smile as he chomps on that gum.