“Vice, virtue. It’s best not to be too moral. You cheat yourself out of too much life. Aim above morality. When you apply that to life, then you’re bound to live it fully.”—Maude

A detective caper. The practically unavoidable car-chase movie. What was once the obligatory Western, now passé, certainly on television. Maybe a straight, uncluttered drama. A CGI extravaganza with monsters, battles and aerial warriors doing somersaults? Maybe even the occasion musical, if loud and unmelodic enough.

Tired of some, or all, of these? What about an off-the-wall black comedy based on an absurd premise which occasionally succumbs to the risqué, often to the implausible and so peculiarly its own entity that, after proving a flop at its premiere, popularly and critically, it has now become a cult classic?

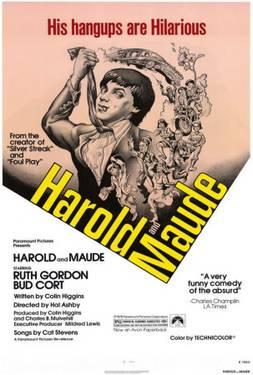

Whacky in the extreme but sometimes touching, Harold and Maude stars a twenty-three-year old Bud Cort and then septuagenarian Ruth Gordon. Cort, earlier seen as the flower child in Sweet Charity (1969) and Private Boone in the M*A*S*H movie (1970), became famous after Harold and Maude, but wanting to avoid typecasting, he has since pursued a variety of roles.

Gordon’s most memorable role is the evil Minnie Castevet in Rosemary’s Baby (1968), a supporting-actress Oscar win. Late in her career, then as a full-fledged octogenarian, she became the oldest, not to mention the cutest, of the Columbo murderers, mystery writer Abigail Mitchell in “Try and Catch Me” (1977). Also a screenwriter, Gordon shared co-writing credit with husband Garson Kanin in a number of films, most notably Adam’s Rib (1949) and Pat and Mike (1952), both vehicles for Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn.

In Harold and Maude, the title characters share one thing in common: they are eccentric—in opposite ways. While Harold is obsessed with death, funerals and staging ritual fake suicides, cocooning himself in preferred seclusion, Maude is obsessed with life and in experiencing everything she can, with lively and bizarre antics, invading other people’s space where Harold is at first afraid to tread.

In the process of Harold being won over to her lifestyle and way of thinking, by movie’s end they become “a couple,” as it were, in the most intimate sense.

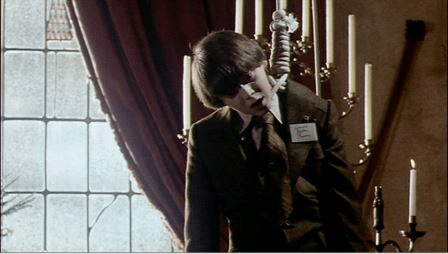

The film begins—no score at first—similar to the setup for a murder mystery, the requisite FTB (finding the body) opening. Only the lower half of a man is seen as a pair of shoes descends a narrow flight of winding stairs and crosses a room. A hand writes a note at a desk. When the person, slowly, solemnly lights two candles in a candelabra, it’s then that the pale, large-eyed face of Harold is seen and a song heard on the soundtrack.

This music is Cat Stevens singing his own “Don’t Be Shy.” His songs (from a previously-released recording, typical of “scores” in the ’70s) permeate the film’s background music, along with “Honorable Death” by Mike Post and Peter Carpenter, appropriately placed in this death-themed movie.

The young man, dressed in suit and tie, proceeds to hang himself.

His mother (Vivian Pickles) enters the room, sees her son’s dangling body and casually walks to the phone. Her first words, “I suppose you think that’s very funny, Harold,” quickly disabuse an audience of any notion that this death is for real, and makes those to follow suspect.

While she cancels a social appointment on the phone, Harold makes a few choking noises for added effect. The impassive mother leaves the room, having suggested Harold be “more vivacious” at dinner that night.

Mom gives Harold a Jaguar, which, with an acetylene torch, he quickly transforms into a hearse.

Harold and Maude first meet at a funeral, no coincidence since attending these rituals for the dead is a shared hobby. She steals cars as a means of transportation—parks one, then steals another—so in one of these handy vehicles she takes Harold to her home, a cluttered renovated Pullman railway passenger coach, built in 1913.

Harold and Maude first meet at a funeral, no coincidence since attending these rituals for the dead is a shared hobby. She steals cars as a means of transportation—parks one, then steals another—so in one of these handy vehicles she takes Harold to her home, a cluttered renovated Pullman railway passenger coach, built in 1913.

Harold is introduced to Maude’s infectious, quirky lifestyle and to aspects of life he has never known. She plays the piano, sings (in a fashion) and paints. She believes in liberty and justice for all creatures. “I used to break into pet shops to liberate the canaries,” she tells him, “but I decided that was an idea way before its time.” Opening a cabinet of music instruments, she says that everyone should play something and gives him a banjo.

The contrast with Harold’s home life is now only accentuated. Further attempts to attract the attention of his wealthy, emotional bereft mother—floating face down in the family pool and blowing his brains out—are all to no avail.

The contrast with Harold’s home life is now only accentuated. Further attempts to attract the attention of his wealthy, emotional bereft mother—floating face down in the family pool and blowing his brains out—are all to no avail.

Mom sends Harold to a psychiatrist (George Wood) who delivers double-talk while both wear identical clothes. Thinking the military would straighten him out, she arranges a meeting with his one-arm uncle (Charles Tyner), a supposed general who jerks his prosthetic arm into a salute with a hidden cord. A victim of war, he praises the glory of war, which prompts a gung-ho, enthusiastic, though put-on response from Harold, climaxing in a planned stunt to kill Maude.

Equally unsuccessful are the arrangements Mom makes for a potential girlfriend. During Mom’s interview, prospect Number One watches through the window as her date climbs on the pool diving board, only to abruptly burst into flames. She flees the house, as does Number Two when Harold hacks off one hand.

In girlfriend Number Three (Susan Madigan), a budding actress, Harold meets his match. After he performs realistic, convincing hari-kari, unfazed, she re-enacts Juliet’s death scene in Romeo and Juliet, clutching a knife from Harold’s collection—“O happy dagger!”—and stabs herself.

In girlfriend Number Three (Susan Madigan), a budding actress, Harold meets his match. After he performs realistic, convincing hari-kari, unfazed, she re-enacts Juliet’s death scene in Romeo and Juliet, clutching a knife from Harold’s collection—“O happy dagger!”—and stabs herself.

Harold and Maude’s relationship quickly grows. Besides leading a number of policemen on merry chases, they steal one officer’s (Tom Skerritt) motorcycle, and Maude, in control, takes the two on a frantic ride. At the funeral of another stranger, Maude steals the hearse. She introduces him to drugs, they share a sunset by a deserted marina, they confess their love, he proposes marriage and they dance to On the Beautiful Blue Danube.

While dancing, she tells him that eighty is the proper age to die. She has taken sleeping pills and “will be gone by midnight.” For someone who loves life, in contrast to Harold, it seems a contradiction of her character.

She dies at the hospital and a distraught Harold drives his Jaguar-hearse frantically through the streets. From a distance, the car is seen careening over a cliff and landing top down on a beach below. On the cliff edge, Harold dances around and on his banjo strums Cat Stevens’ “If You Want to Sing Out, Sing Out.”

She dies at the hospital and a distraught Harold drives his Jaguar-hearse frantically through the streets. From a distance, the car is seen careening over a cliff and landing top down on a beach below. On the cliff edge, Harold dances around and on his banjo strums Cat Stevens’ “If You Want to Sing Out, Sing Out.”

One last “suicide”? Maybe.

Parts of Harold and Maude might be unappetizing for some tastes. Most critically, Maude’s suicide and a scene after the two have made love, Harold blowing bubbles from a bubble jar, may seem against the film’s established whacky spirit. For others, this very whackiness, whatever comes, may be the needed relief from the conventional film—the weak remake, the stale sequel, the dumb comedy.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5mz3TkxJhPc[/embedyt]