“They reckon it’s a good life to have reached forty. We’re both past it, and look at us!”— Robin to Little John

People don’t go to the movies as much as they used to, certainly not the way they did in the ’30s and early ’40s, when attendance reached its high point in 1943-44. The first large decline, which began in the mid-’60s and has continued, was, and is, due to TV, DVDs, Internet screening and the ever-increasing ticket price. Also have been the gradual changes on screen: an anything-goes, yet highly limited subject matter, the adolescent level of appeal and the larger-than-life monsters and superheroes which exist in an unreal world engineered by CGI. Just as the average reading level ofNew York Times bestsellers has dropped from an eighth-grade level in the ’60s to sixth grade in this decade, movie subject matter grows more and more simplistic.

And what is inside the theater has also discouraged the traditional movie-goer: the ring of cell phones, the light from IPads, the deafening IMAX sound and the talking—people are gradually becoming less and less considerate of one another.

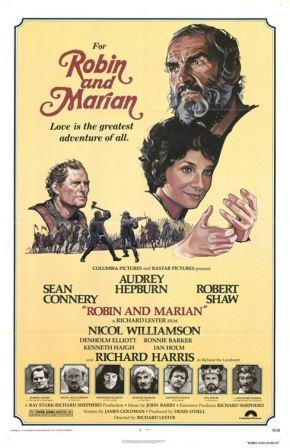

Robin and Marian, then, is, in a sense, the victim of its time, forty years ago when it was made. Its title suggests a romantic adventure film, perhaps a revival of the traditional, idealized love story of the “old school.” Sadly for some movie-goers, it is neither a romantic adventure nor a revival.

In fact, R&M reiterates a quite different, still on-going trend, best represented by the Peter O’Toole/Katharine Hepburn Lion in Winter (1968) and Kevin Costner’s Robin Hood, Prince of Thieves (1991). All three films endeavor to be authentic, to portray the way it really was in medieval times—the cold, dirty castles, chickens and pigs running loose, the unwashed, smelly people, even their bad teeth. At the same time, and contradictorily inauthentic, everyone speaks contemporary English, including modern-day slang—”Oh, it’s only my snack” in Becket (1964)—which seems to bother no one.

This striving for realism makes even more sharp any comparison with the definitive Robin Hood depiction, the idealistic steal-from-the-rich-to-give-to-the-poor 1938 Errol Flynn version, The Adventures of Robin Hood. Here, Robin is immaculately dressed, golden hair in place, doing good for a totally pure and righteous Lady Marian in her resplendent bliauts fresh from the wardrobe department, with no danger of being soiled in the clean castles with their well-scrubbed walls.

This striving for realism makes even more sharp any comparison with the definitive Robin Hood depiction, the idealistic steal-from-the-rich-to-give-to-the-poor 1938 Errol Flynn version, The Adventures of Robin Hood. Here, Robin is immaculately dressed, golden hair in place, doing good for a totally pure and righteous Lady Marian in her resplendent bliauts fresh from the wardrobe department, with no danger of being soiled in the clean castles with their well-scrubbed walls.

In R&M, battle is portrayed realistically, with plenty of blood, and accurate hand-to-hand combat shows the awkwardness of handling heavy broadswords, though decidedly unawkward in the hands of a first-class knight of the time. Flynn and Basil Rathbone fight with undersized broadswords more in the manner of rapiers.

Whatever the realism and accuracy in R&M, it doesn’t seem right; it seems to betray a long-standing code of movie tradition.

Many h umorous touches suggest that, perhaps, the film is all tongue in cheek anyway. In the beginning, a soldier pinches his finger while placing a heavy stone on a catapult. One of the merry men complains, “We’re too old for this sort of thing,” as he climbs a tree to watch for the sheriff’s army. Robin and Little John (Nicol Williamson) are exhausted scaling a portcullis and wall. Robin helps up the Sheriff of Nottingham (Robert Shaw) after they’ve kissed their swords and prepare to fight one another. Robin later exclaims to a foe that their combat has tired him.

umorous touches suggest that, perhaps, the film is all tongue in cheek anyway. In the beginning, a soldier pinches his finger while placing a heavy stone on a catapult. One of the merry men complains, “We’re too old for this sort of thing,” as he climbs a tree to watch for the sheriff’s army. Robin and Little John (Nicol Williamson) are exhausted scaling a portcullis and wall. Robin helps up the Sheriff of Nottingham (Robert Shaw) after they’ve kissed their swords and prepare to fight one another. Robin later exclaims to a foe that their combat has tired him.

Life has changed drastically for Robin and Marian since they stepped outside those enormous doors of Nottingham Castle in 1938 and waved farewell to King Richard the Lion-Heart (Ian Hunter), with a presumption they will live happily every after.

Sean Connery as Robin and Audrey Hepburn as Marian, now an abbess in an isolated convent, aren’t the “newer” versions of 1938 but the older ones. Now, twenty or so years later, the couple are middle-aged, self-analytical and philosophical. They seem burdened with the trials and turmoils of the twentieth century, and strangely “modern,” dissatisfied with their times, their contemporaries and, yes, even themselves and their lives.

Robin has been disillusioned by the “Holy” Crusades and by the barbarism of Richard (Richard Harris). In one of the best dialogues of the film, he describes Richard’s only victory in the Holy Land, how the king was sick in bed, but roused himself in time to slaughter the Moslem prisoners, even “opening their insides” in search of jewelry—contrary to the almost saintly image of the 1938 Richard, however inaccurate. This scene reflects the abundant talking—screenplay by John Goldman who also scripted The Lion in Winter—but there are too few good dialogue scenes.

Robin has been disillusioned by the “Holy” Crusades and by the barbarism of Richard (Richard Harris). In one of the best dialogues of the film, he describes Richard’s only victory in the Holy Land, how the king was sick in bed, but roused himself in time to slaughter the Moslem prisoners, even “opening their insides” in search of jewelry—contrary to the almost saintly image of the 1938 Richard, however inaccurate. This scene reflects the abundant talking—screenplay by John Goldman who also scripted The Lion in Winter—but there are too few good dialogue scenes.

Marian, however, suffers a greater disillusionment than Robin. She confides to him that she doesn’t know who she is—whether the woman he knew or the abbess—and she decides she’d be glad to be either one if she could find a trace of one or the other in herself. Although in her early scenes she seems to be of great will and of high principles, she soon becomes a bit wishy-washy.

In the first shot of the film, three apples sit in a windowsill, then, in the next frame, the apples are shriveled—a motif and meaning yet to be revealed? Well over half way into the film, just before Robin and Marian are reunited, she is mixing something in a bowl and adding a liquid from a purple bottle. Giving a bedridden old woman the bowl, she comments causally, “This will relieve your pain.” Could it be that Marian’s time is devoted to pursuits other than vespers and healing, like “relieving” the sick of their misery, a practitioner of euthanasia?

Following a wagon mishap in a creek, the two reunited lovers have perhaps their most romantic love scene. She touches her fingers to the scars on his chest and shoulders and bemoans how firm and unmarred his body used to be, implying an intimacy that is never even remotely suggested—prohibited by the censoring Hays Office—between Flynn and his Maid Marian, Olivia de Havilland.

Following a wagon mishap in a creek, the two reunited lovers have perhaps their most romantic love scene. She touches her fingers to the scars on his chest and shoulders and bemoans how firm and unmarred his body used to be, implying an intimacy that is never even remotely suggested—prohibited by the censoring Hays Office—between Flynn and his Maid Marian, Olivia de Havilland.

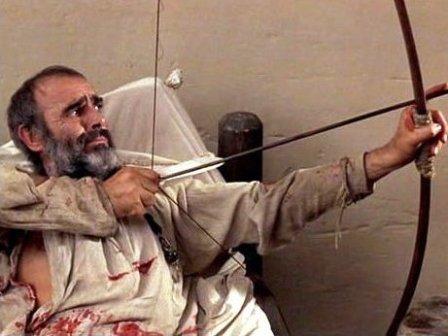

In the ludicrous climax, using the same purple bottle, she poisons herself and Robin, who, strangely, calmly, accepts his fate—the best way, he reasons. The two die together, but not before Robin has shot an arrow out of the window into the blazing sun. “Where this falls, John, put us close, and leave us there.” It’s the familiar window, and on the sill are the three shriveled apples.

The supporting cast consists of the best of British screen stars: Denholm Elliott (A Room with a View, Raiders of the Lost Ark) as Will Scarlett, Ian Holm (Chariots of Fire) as King John, Ronnie Barker (many British TV series) as Friar Tuck, Kenneth Haigh (Cleopatra, 1963) as Sir Ranulf, Bill Maynard (also mainly in British TV) as Mercadier and Esmond Knight (Olivier’s Hamlet) as an old defender.

The supporting cast consists of the best of British screen stars: Denholm Elliott (A Room with a View, Raiders of the Lost Ark) as Will Scarlett, Ian Holm (Chariots of Fire) as King John, Ronnie Barker (many British TV series) as Friar Tuck, Kenneth Haigh (Cleopatra, 1963) as Sir Ranulf, Bill Maynard (also mainly in British TV) as Mercadier and Esmond Knight (Olivier’s Hamlet) as an old defender.

The color in Robin and Marian is acceptable, subdued and smoky, hardly the clean, clear, brilliant three-strip Technicolor of Flynn’s masterpiece. The shaking camera, shooting into the sun, the distortions and reflections are expected in today’s cinematography, here by David Watkin (Out of Africa, Chariots of Fire).

Knowing the looming impact of that 1938 film, it’s impossible, even with a deliberate effort, to justly compare Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s score with John Barry’s. Korngold’s is a fairytale accompaniment to a fairytale; Barry’s is often nondescript, even when in the foreground, maintaining the pessimistic atmosphere of the narrative.

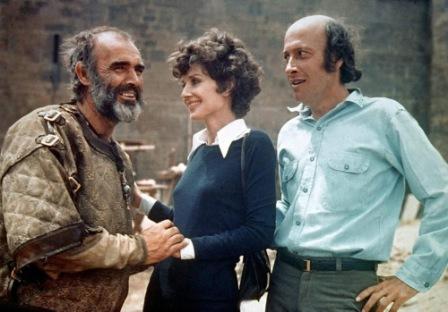

The acting is a mixed bag, perhaps the result of a lack of attention by director Richard Lester (A Hard Day’s Night). Harris’ shouting and almost mock oratory as Richard borders on over-acting and satire. By contrast, as the sheriff, Shaw, already a more subtle, subdued actor than Harris, seems to amble through his lines, quite a contrast with Alan Rickman’s eccentric, though clearly memorable take on the role in Costner’s movie.

Connery is steadfast in his characterization of Robin, the middle-aged, mellowed warrior, tired of war and, to a degree, tired of a life that has changed since his return from the Crusades.

Connery is steadfast in his characterization of Robin, the middle-aged, mellowed warrior, tired of war and, to a degree, tired of a life that has changed since his return from the Crusades.

Hepburn must receive the highest honors for her underplayed, well-controlled performance, avoiding the possible extremes of her character’s two-sided personality. It’s not her fault that she can’t make her suicide and her murder of Robin plausible, despite her speech about loving him more than morning prayers, more than fields she had planted with her own hands, more than sunlight and more than God.