A tennis star plays a match with murder!

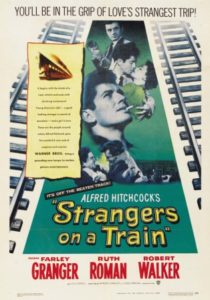

Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train, clearly among his five greatest films, begins and ends with a train ride and with the line, “I beg your pardon, but aren’t you Guy Haines?” And during the one hundred minutes or so in between beginning and end, star tennis player Guy Haines (Farley Granger) has the nightmare of his life. On a train from Washington, D.C., he by chance meets Bruno Anthony (Robert Walker) whose small talk reveals a surprising knowledge of his personal life. From reading the society page, Bruno knows, for instance, that the celebrity is seeking a divorce from an obstinate wife so as to marry a senator’s daughter.

Over drinks and a meal of overdone lamb chops, Bruno casually makes a most unusual proposal, an exchange that he says would benefit both. What if Guy had someone he wanted to get rid of, say, this wife of his, and he, similarly, had someone, oh, say, his hated father. Why, they would exchange murders; each would murder a total stranger—with no connection. “Like,” Bruno says, “you do my murder and I do yours. For example, your wife, my father. Crisscross.”

Earlier, a close-up of a pair of walking feet had opened the film, much as, twice, a pair of train tracks had crossed one another. Crisscross. Strangers on a Train is, in fact, an extension of Hitchcock’s obsession with doubles in the manner of Shadow of a Doubt, made eight years earlier. In Strangers there are two men on a train, two women at a party, two pairs of detectives, two boys and two old men in two carnival scenes, a pair of crossed tennis rackets on a cigarette lighter—on and on, almost ad infinitum. In a further example, Hitch makes his traditional cameo appearance boarding a train with a double bass, which is as large as he is.

Just as Hitchcock cast handsome, leading-man Joseph Cotton as the villain in Shadow of a Doubt, the director assigned the role of the psychopath Bruno, again against type, to the attractive Walker whose boy-next-door image had been well established in The Clock and Since You Went Away. This is his finest performance.

Just as Hitchcock cast handsome, leading-man Joseph Cotton as the villain in Shadow of a Doubt, the director assigned the role of the psychopath Bruno, again against type, to the attractive Walker whose boy-next-door image had been well established in The Clock and Since You Went Away. This is his finest performance.

Strangers on a Train is, by the way, part of a box set, The Best of Warner Bros. 20-Film Collection: Thrillers, newly released to celebrate the studio’s ninetieth anniversary, running throughout 2013. The films fall between 1931 and 2010 and include The Maltese Falcon, Dirty Harry, The Fugitive, The Shawshank Redemption, L.A. Confidential and Inception. One other Hitchcock film, North by Northwest, is also part of the collection.

Guy doesn’t take Bruno’s murder exchange proposal seriously, thinking it’s as reliable as his theory for legalizing bigamy which Bruno says he will share with him another time. When Guy is leaving the train at Metcalf, Bruno asks boyishly, “Do you think my theory is okay, Guy? You like it?” Guy humors him. “Sure, sure, Bruno. They’re all okay.”

After Guy has left, Bruno picks up the tennis player’s forgotten lighter with the crossed tennis rackets, smiles and says to himself, “Crisscross.”

He was serious, and one night, as part of his half of the presumed agreement, he follows Guy’s wife Miriam (Laura Elliott) to an island carnival. Accompanied by “The Band Played On” from a distant calliope, he strangles her. In one of at least two Hitchcock tours de force in the film, cinematographer Robert Burks uses a large distorting lens to obtain a screen-size image of the killing, reflected in one of the lenses of Miriam’s glasses, which had fallen to the ground. Strangers is the first of twelve films Burks would shoot for Hitchcock.

He was serious, and one night, as part of his half of the presumed agreement, he follows Guy’s wife Miriam (Laura Elliott) to an island carnival. Accompanied by “The Band Played On” from a distant calliope, he strangles her. In one of at least two Hitchcock tours de force in the film, cinematographer Robert Burks uses a large distorting lens to obtain a screen-size image of the killing, reflected in one of the lenses of Miriam’s glasses, which had fallen to the ground. Strangers is the first of twelve films Burks would shoot for Hitchcock.

In several unexpected and clandestine meetings and phone calls, Bruno attempts to persuade Guy to follow through on their “agreement.” Once, Guy pretends to agree and goes to the father’s house one night, even armed with a gun, but when he politely tries to awaken the man—“Mr. Anthony! Don’t be alarmed, but I must talk to you about your son.”—the hand that reaches out to turn on the bed table lamp is Bruno’s.

At a party, the uninvited Bruno, playing the debonair guest, elegantly demonstrates on an elderly woman (Norma Varden) the art of strangulation, one of Hitch’s favorite killing methods. When Bruno sees, across the room, the daughter (Patricia Hitchcock) of a senator (Leo G. Carroll), he is transfixed, breathing heavily, what today would be called a panic attack. The young woman’s face—the glasses, the hair style—reminds him of Miriam. In his catatonic state, he begins strangling the woman in earnest.

At a party, the uninvited Bruno, playing the debonair guest, elegantly demonstrates on an elderly woman (Norma Varden) the art of strangulation, one of Hitch’s favorite killing methods. When Bruno sees, across the room, the daughter (Patricia Hitchcock) of a senator (Leo G. Carroll), he is transfixed, breathing heavily, what today would be called a panic attack. The young woman’s face—the glasses, the hair style—reminds him of Miriam. In his catatonic state, he begins strangling the woman in earnest.