“Oh, wake up, Norma—you’d be killing yourself to an empty house. The audience left twenty years ago.” —— Joe Gillis to Norma Desmond

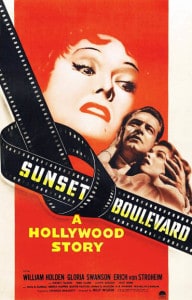

That 1950 movie Sunset Blvd. was at the time, and remains today, unique in many ways, a milestone in movie history, besides being a great film, with one of the best movie scripts ever written. However wrong it looks, the abbreviation and period in the title are correct as they appear in the main title, stenciled on a street curb. Foremost, perhaps, the film was the first exposé of Hollywood, a none-too-complimentary look which ignited the ire of Louis B. Mayer, the most passionate of moguls, who promoted his own image of homespun America in the Andy Hardy series from 1937 until 1946.

Surprisingly, Paramount Pictures, the studio responsible for Sunset Blvd., okayed this script that was unflattering to the movie business and allowed director Billy Wilder to shoot the film on the premises—showing the most famous and picturesque of the entrances, the back lot, the inside and outside of the writers’ studios and a working sound stage. Samson and Delilah was being filmed at the time, and to add even more authenticity to things, its director Cecil B. DeMille appears with Gloria Swanson as a weak, vacillating director.

Swanson, a famous silent screen star as far back as 1914, had practically disappeared from the screen with the advent of sound. She made only seven films—talkies—between 1929 and 1950. Despite the praise she received for Sunset Blvd. and her third Oscar nomination (losing, however, along with Bette Davis, to Judy Holiday), a comeback or, rather “return” as her screen character Norma Desmond preferred, did not materialize. Swanson compromised with some TV and made two forgettable theatrical films before her final big screen appearance in Airport in 1970.

Although a forgotten ex-silent screen star and often married—that much she, indeed, had in common with Norma Desmond—Swanson was otherwise an outgoing, business-minded artist with none of the psychoses of the woman she portrayed.

Although a forgotten ex-silent screen star and often married—that much she, indeed, had in common with Norma Desmond—Swanson was otherwise an outgoing, business-minded artist with none of the psychoses of the woman she portrayed.

While Sunset Blvd. did little for Swanson, the film did much to revive William Holden’s sagging career—that and the good fortune of his also co-starring that year with relative newcomer Holiday in Born Yesterday. After his promising portrayal of a boxer in Golden Boy in 1939, he had settled rather wastefully into light, boy-next-door roles with the likes of Dear Ruth, Dear Wife and Father Is a Bachelor. He truly “returned” with Stalag 17, Sabrina and The Country Girl, reaching his peak—certainly financially in receiving a percentage of the large profits—with The Bridge on the River Kwai. As he aged, no longer the romantic lead, his good looks damaged by alcoholism, he turned to more mature roles. There were two more outstanding films to come—The Wild Bunch, shockingly bloody and graphic (at the time, anyway), and Network, which earned him the last of three Best Actor Oscar nominations. He won his only Oscar in 1953 for Stalag 17, another Wilder film.

In the already fading light of Hollywood’s “Golden Age,” 1950 was an especially good year, with at least five great, or near-great, films: Sunset Blvd., The Third Man, All About Eve, The Asphalt Jungle and Born Yesterday. Among these five, there were thirty-six Oscar nominations. Sunset Blvd. received three of the statuettes against six for its stiffest competition, All About Eve. Greatly debated over the years, it has slowly emerged that, between these two movies, most critics now regard Sunset Blvd. as the better film.

In Sunset Blvd., Holden isn’t a typical romantic leading man. He has no real, passionate clinches with his main co-star, Swanson—sex, even love, wasn’t what his character is after, often visibly uncomfortable beside her—and those apparently serious embraces he does have with his other female co-star, Nancy Olson, are hindered by his character’s haunted duplicity and that sordid association with the first lady.

Sunset Blvd. is a flashback, one of the greatest in film. The tale begins with a man floating, face down, in the swimming pool of a haunted mansion of sorts. As so often with Wilder movies, there is a narrator, and in this case the narration is a key ingredient, deserving third billing after Holden and Swanson. That the narrator is the dead man may present, to some, a problem of logic, certainly at film’s end. “Yes,” he begins, “this is Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles, California. It’s about five o’clock in the morning. That’s the homicide squad, complete with detectives and newspaper men. A murder has been reported from one of those big houses in the ten thousand block. . . . Let’s go back about six months and find the day when it all started——”

Sunset Blvd. is a flashback, one of the greatest in film. The tale begins with a man floating, face down, in the swimming pool of a haunted mansion of sorts. As so often with Wilder movies, there is a narrator, and in this case the narration is a key ingredient, deserving third billing after Holden and Swanson. That the narrator is the dead man may present, to some, a problem of logic, certainly at film’s end. “Yes,” he begins, “this is Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles, California. It’s about five o’clock in the morning. That’s the homicide squad, complete with detectives and newspaper men. A murder has been reported from one of those big houses in the ten thousand block. . . . Let’s go back about six months and find the day when it all started——”

Next, the camera approaches, Hitchcock-style, a window of an apartment. Inside, Joe Gillis (Holden), the man in the pool, is hacking away at a typewriter. He writes Hollywood screenplays—for “B” movies mostly, only he hasn’t sold anything in sometime. He’s down on his luck, to put in mildly, and out of cash. When the finance company men knock on the door, come to repossess his car, he tells the two guys he loaned the vehicle to a friend. The men give him until noon the next day to hand over the car, then leave.

Gillis drives the car, hidden in a parking lot, to Paramount studios, to see pill-popping, ulcer-plagued executive Sheldrake (Fred Clark), who is indifferent toward the writer’s idea for a baseball picture and turns down his request for a personal loan. Sheldrake’s script reader Betty Schaefer (Olson) enters, criticizing a recent submission, unaware Gillis is the author.

On the way back to his apartment, Gillis spots, mid-narration, the repossession men and floors the car, turning into—yep!—Sunset Boulevard. A tire blows and, rounding a curve on the wheel rim, he steers into the nearest driveway and into a double-car garage.

The rundown mansion (later torn down and not on Sunset Boulevard) is “a great big white elephant of a place, the kind crazy movie people built in the crazy Twenties.” It is unkempt and seems deserted. Walking around to the back, Gillis discovers that it has at least one inhabitant. In quite a contrast with the way she will appear at film’s end, the mistress of the house appears in shadow, partially concealed behind a set of slat blinds and wearing dark glasses. “You there, why are you so late?” she asks, obviously expecting someone else.

Gillis is ushered into the house by the butler Max (Erich von Stroheim), who says that Madame is waiting and adds, “If you need any help with the coffin, call me.” There are suggestions, already, that this is part horror movie; now, with that line, as has been hinted earlier, the film is also part comedy.

Gillis is ushered into the house by the butler Max (Erich von Stroheim), who says that Madame is waiting and adds, “If you need any help with the coffin, call me.” There are suggestions, already, that this is part horror movie; now, with that line, as has been hinted earlier, the film is also part comedy.

But, now, the fugitive from the finance company exchanges with the lady of the house some of the most famous lines in movie history. He recognizes her: “You’re Norma Desmond! You used to be in silent pictures, used to be big.” And she replies, “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small.”

Turns out Norma was expecting an animal undertaker for her recently deceased pet chimpanzee which is laid out before a lighted fireplace.

Turns out Norma was expecting an animal undertaker for her recently deceased pet chimpanzee which is laid out before a lighted fireplace.

Learning he is a screenwriter, Norma cajoles him—it’s not very hard—into working on her script about Salome, intended as her “return,” not “comeback,” vehicle. Passing himself off as a busy, high-paid writer and she indicating that money is no problem, they make a deal. Of course, she can’t let the manuscript—“enough for six important pictures,” he says—out of her sight, so he will have to be a live-in writer—and a “live-in” something else as soon transpires.

As Gillis settles into a leaky, stark room over the garage, he looks out the window. Indeed, the pet undertaker has arrived and a chimpanzee burial is underway in the garden. In one of the most picturesque of his copious narrations, Gillis observes: “Come to think of it, the whole place seemed to have been stricken with a kind of creeping paralysis, out of beat with the rest of the world, crumbling apart in slow motion. There was a tennis court, or, rather, the ghost of a tennis court, with faded markings and a sagging net. And of course she had a pool. Who didn’t then? Mabel Norman and John Gilbert must have swum in it ten thousand midnights ago, and Vilma Banky and Rod La Rocque. It was empty now—or was it?” And the screen shows a colony of rats in the bottom of the pool.

As Gillis settles into a leaky, stark room over the garage, he looks out the window. Indeed, the pet undertaker has arrived and a chimpanzee burial is underway in the garden. In one of the most picturesque of his copious narrations, Gillis observes: “Come to think of it, the whole place seemed to have been stricken with a kind of creeping paralysis, out of beat with the rest of the world, crumbling apart in slow motion. There was a tennis court, or, rather, the ghost of a tennis court, with faded markings and a sagging net. And of course she had a pool. Who didn’t then? Mabel Norman and John Gilbert must have swum in it ten thousand midnights ago, and Vilma Banky and Rod La Rocque. It was empty now—or was it?” And the screen shows a colony of rats in the bottom of the pool.

Gillis, perhaps because he is a weak man of questionable character, easily settles into the routine of the household—endless nights watching Norma’s old silent movies, wrestling with “that silly hodgepodge of melodramatic plots” that was her script, playing stooge in a card game with forgotten silent stars Buster Keaton, H. B. Warner and Anna Q. Nilsson, the “waxworks” as Gillis calls them, and a New Year’s party in which he and Norma are the only guests, complete with dance band.

Billy Wilder shows in several subtle ways—sans any passionate bedroom scenes—what other “service” Gillis is rendering besides writing. Long before the end of those six months, between his arrival and that final dip in the pool, Gillis is “promoted” from the garage room to the “husbands’ room” which adjoins Norma’s bedroom, and all that that implies. (Max informs him that he was the first of Norma’s three husbands.) Norma takes him shopping for a new suit and the salesman (Archie Twitchell) whispers to him with a smirk, “As long as the lady is paying for it, why not take the Vicuña?” Gillis has grown suddenly informal around her. Emerging from the pool, which she had especially filled for him, he is now relaxed and informal. “Turn around, darling,” she says. “Let me dry you.” He seems all too willing to oblige.

Billy Wilder shows in several subtle ways—sans any passionate bedroom scenes—what other “service” Gillis is rendering besides writing. Long before the end of those six months, between his arrival and that final dip in the pool, Gillis is “promoted” from the garage room to the “husbands’ room” which adjoins Norma’s bedroom, and all that that implies. (Max informs him that he was the first of Norma’s three husbands.) Norma takes him shopping for a new suit and the salesman (Archie Twitchell) whispers to him with a smirk, “As long as the lady is paying for it, why not take the Vicuña?” Gillis has grown suddenly informal around her. Emerging from the pool, which she had especially filled for him, he is now relaxed and informal. “Turn around, darling,” she says. “Let me dry you.” He seems all too willing to oblige.

While undeterred by it all and enjoying his gifts, Gillis has learned a few things about the two occupants of this strange, gaudy house. First of all, Norma is crazy, as he had to know from the first, as well as suicidal and psychotically narcissistic—watching her old movies, autographing photos of herself for all those “fans out there” and delighting in the endless photographs of herself. As Gillis tells his audience, “How could she breathe in that house so crowded with Norma Desmonds, more Norma Desmonds and still more Norma Desmonds?”

While undeterred by it all and enjoying his gifts, Gillis has learned a few things about the two occupants of this strange, gaudy house. First of all, Norma is crazy, as he had to know from the first, as well as suicidal and psychotically narcissistic—watching her old movies, autographing photos of herself for all those “fans out there” and delighting in the endless photographs of herself. As Gillis tells his audience, “How could she breathe in that house so crowded with Norma Desmonds, more Norma Desmonds and still more Norma Desmonds?”

Gillis learns that Max, who plays Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor on the organ and serves caviar and champagne on a cart in white gloves, was once one of “three young directors who showed promise in those days: D. W. Griffith, Cecil B. DeMille and Max von Mayerling.” Mayerling is a fictional pseudonym for the once-great silent director Stroheim himself, who had directed Swanson in 1929 in Queen Kelly, one of the films Norma and Gillis watch. Although Max is now reduced to butler and chauffeur, unlike Gillis’ motives, he remains a servant to this unsettled woman out of a deep love, forging fan letters, waiting on her despite her indifference and even advising her on her makeup.

Much of the time, Gillis is seeing a woman closer to his own age, that Betty Schaefer from Sheldrake’s office. Together, they are working in the evenings at Paramount on an early Gillis script that she feels has possibilities. She is clearly falling for him, despite her relationship with the upstanding Artie Green (Jack Webb), and he for her, though he sees the absurdity of it all. His conscience is beginning to bother him.

Much of the time, Gillis is seeing a woman closer to his own age, that Betty Schaefer from Sheldrake’s office. Together, they are working in the evenings at Paramount on an early Gillis script that she feels has possibilities. She is clearly falling for him, despite her relationship with the upstanding Artie Green (Jack Webb), and he for her, though he sees the absurdity of it all. His conscience is beginning to bother him.

Norma has Max take the finished manuscript to Cecil B. DeMille at Paramount, and before long, indeed, the phone does ring. It’s Gordon Cole from the studio. In Norma’s twisted rationale, now ostensibly on the brink of her dream coming true, she insists on speaking only to DeMille. She soon relents, however, and Max drives Norma and Gillis to the studio. DeMille is cagey about the script and puts her off regarding any screen appearance, but she is too lost in her own world to sense the subterfuge. Meanwhile, Max discovers that Cole was calling only to see about renting her car, a ’20s-era Isotta-Fraschini, for a Bing Crosby picture. Neither Max nor Gillis has the “guts” to tell her as she undergoes extensive body and facial rejuvenation for her imagined screen return.

One evening, Max calls Gillis at the studio. Norma has tried to kill herself with his razor, all others hidden away, a precaution along with doors that have no locks. As Max says, “Madame has moments of melancholy.” Because Gillis rushes to her side, he must have some residual affection for her. Out of some kind of spite, perhaps because he’s desperate to “wipe the whole nasty mess out of my life,” he tells Betty to come by the house. Avoiding the word itself, even if 1950s censors would have allowed it, he announces he is nothing more than a gigolo. The situation is simple, he says: “Older woman who’s well-to-do, younger man who’s not doing too well.”

One evening, Max calls Gillis at the studio. Norma has tried to kill herself with his razor, all others hidden away, a precaution along with doors that have no locks. As Max says, “Madame has moments of melancholy.” Because Gillis rushes to her side, he must have some residual affection for her. Out of some kind of spite, perhaps because he’s desperate to “wipe the whole nasty mess out of my life,” he tells Betty to come by the house. Avoiding the word itself, even if 1950s censors would have allowed it, he announces he is nothing more than a gigolo. The situation is simple, he says: “Older woman who’s well-to-do, younger man who’s not doing too well.”

Betty is undaunted, obviously a straightforward, uncomplicated love foreign to both Norma and Gillis. “Get your things,” she says. “All my things?” he replies. “All the eighteen suits, the custom-made shoes, all six dozen shirts, the cuff links, platinum chains and cigarette cases?” Betty finally admits defeat and leaves, alone.

When Gillis turns to pack, renouncing all the gifts, Norma, already hysterical, shoots him as he passes by the pool.

Flashback over. Back to the present and that body floating in the water and the array of policemen and reporters, including, in another cameo, Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper. At the top of the staircase before the assembled police, reporters and TV cameramen, Norma says she is ready. The forever faithful Max, standing among the news cameras, describes Salome’s scene to her, then says, “All right! Cameras! Action!” Norma, now completely unencumbered by reality, descends the staircase as Salome. Then at the bottom, she says, “All right, Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up.”

Flashback over. Back to the present and that body floating in the water and the array of policemen and reporters, including, in another cameo, Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper. At the top of the staircase before the assembled police, reporters and TV cameramen, Norma says she is ready. The forever faithful Max, standing among the news cameras, describes Salome’s scene to her, then says, “All right! Cameras! Action!” Norma, now completely unencumbered by reality, descends the staircase as Salome. Then at the bottom, she says, “All right, Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up.”

“So they were turning after all, those cameras,” continues Gillis’ narration. “Life, which can be strangely merciful, had taken pity on Norma Desmond. The dream she had clung to so desperately had enfolded her.” Joe Gillis narrating? Isn’t he dead, off to the morgue by now?! Doesn’t matter. If the audience accepted the narration of a dead man during the film, they shouldn’t have a problem now.

accepted the narration of a dead man during the film, they shouldn’t have a problem now.

After all, the narration is one of the stars of the film, one of the best examples of Billy Wilder’s command of the English language, this émigré from Nazi Germany, this Austro-Hungarian who wrote better screenplays than most native Americans. Further proof is the Oscar the film received for Story and Screenplay, as it was called then, for Wilder and his co-writers, frequent partner Charles Brackett and, now, D. M. Marshman, Jr. In 1956, a clearer distinction in the screenplay categories would become Original and Adapted, and the third and confusing Story and Screenplay would be dropped the following year.

Franz Waxman, also an émigré from the Nazis, in fact beaten up on a Berlin street, won the second of the film’s three Oscars for his score. (The other Oscar was for B&W Art-Set Direction; incidentally, the Best Color Art-Set Direction was awarded to the aforementioned Samson and Delilah.) Waxman, who was first noticed for his music for The Bride of Frankenstein in 1935, would score three other Wilder films and win his second Oscar in 1951 for A Place in the Sun. Although directed by George Stevens, that film has a similar link to water and murder: Shelley Winters is drowned in a lake by Montgomery Clift.

In its strong support, the music in Sunset Blvd. is almost, though not quite, equal to the narration in importance, both reinforcing the scenes as background per se and in punctuating a Gillis comment or action with a question, affirmation or punch line of sorts. Think of the cynically comical woodwinds that fill the silence as Gillis looks maliciously at the suit salesman after his “Vicuña” sneer.

Or the sleazy saxophone when Norma hands Gillis money for some cigarettes. Or, at poolside, when Norma’s theme is used behind her pathetic confession that she has never been happier. Or the zany silent screen music for Norma’s impersonation—Swanson is quite good, actually—of Charlie Chaplin, complete with mustache, bowler hat and cane, dexterously twirled. Or Waxman’s sly disguise of Paramount’s then famous “Eyes and Ears of the World” newsreel theme as Gillis and Betty walk through the studio back lot.

In the main title, the opening hard-hitting, rhythmic theme (after a brief trumpet fanfare) may remind some attentive listeners of the main theme from Igor Stravinsky’s Pulcinella. The tune will later add excitement to the chase when Gillis eludes the car repossessors.

In the main title, the opening hard-hitting, rhythmic theme (after a brief trumpet fanfare) may remind some attentive listeners of the main theme from Igor Stravinsky’s Pulcinella. The tune will later add excitement to the chase when Gillis eludes the car repossessors.

The present opening of Sunset Blvd., with Holden floating in the pool, isn’t the original one. On one of the few occasions, it seems, when Billy Wilder misjudged anything regarding motion pictures, the first version took place in a morgue. Holden and the corpses talked among themselves, with lights under the sheets, most macabre of all when a young boy described drowning not being so bad when he opened his mouth and let in the water! The audience either laughed or walked out, or both.