“It would take the pity of God to get to the bottom of things.”— Miss Madrigal

The house, which overlooks the sea and has a view of what appears to be chalk cliffs, shelters an unusual array of individuals, variant in age, world outlook and, by all means, psychological disposition. It is not the house itself which makes them so different, or at times so antagonistic toward one another, but what the house means to each of them, for all but one have come from somewhere else—and, in the end, one must leave for personal salvation.

A little cryptic? Perhaps.

The house has no address, only that it is set back from the street, with an immaculate lawn and near a town, maybe a city—at least a place large enough to have a hardware store where padlocks may be purchased, a tennis court where more than one kind of game may be played (a game of initials, perhaps?), a large park and double-decker buses. The house appears to be in the suburbs, probably of London, isolated in more ways than one. Set off by itself, inside it seems pleasant enough, warm and airy but not altogether “settled”—and not as to the solidarity of its foundation, either.

And what of bonfires? Yes, bonfires. They are allowed, but a reliable source confides that they are gradually getting smaller.

Miss Madrigal—yes, spelled the same as those English and Italian songs of past centuries—has arrived from a place or places unknown and warns the mistress of the house, “You’re trying to grow flowers in chalk. . . . But nothing in the world has been done for them. Have you time, Mrs. St. Maugham, before death, to thrown away season after season?”

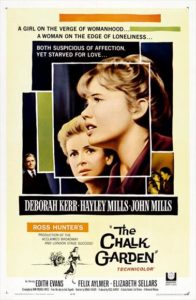

The first woman to come to the house, in fact her arrival opens the film, which by the way is The Chalk Garden (1964), isn’t Miss Madrigal but another applicant for governess to a child whose superficial maturity seems to run the household. Since the two applicants sit together, Miss Madrigal—she has no first name—makes the first of a number of perceptive observations. About the mousy first applicant: “She’s a little light-fingered,” she informs Maitland the butler (John Mills).

Further, Miss Madrigal (Deborah Kerr), already, after so short an acquaintance, remarks that the child is “outlandish,” and Maitland counters, “This is an outlandish household.” And when the first applicant flees, he locks the nearest door and tells the lady who remains, “You’re not going to escape so easily. If you get away, I shall end up being governess as well as everything else.”

Further, Miss Madrigal (Deborah Kerr), already, after so short an acquaintance, remarks that the child is “outlandish,” and Maitland counters, “This is an outlandish household.” And when the first applicant flees, he locks the nearest door and tells the lady who remains, “You’re not going to escape so easily. If you get away, I shall end up being governess as well as everything else.”

The grandmother (Edith Evans in an Oscar-nominated supporting role) at first rejects Miss Madrigal as a suitable governess for her granddaughter Laurel (Hayley Mills looking and playing younger than her eighteen years), but later, when Mrs. St. Maugham learns the applicant has a knowledge of gardens, even having tended one, she changes her mind, a hint that perhaps she values her flowers more than her granddaughter.

What follows borders on soap opera . . . well, undoubtedly it could be taken for soap opera, chiefly in the film’s themes. First and foremost, there’s this mysterious Miss Madrigal, whose presumed dark past Laurel vows to expose—and vows as well to send her away, as she has sent away so many other governesses, not counting the one she says was eaten by a shark. “Outlandish” this child, remember! “Why do you come here?” Laurel asks and quickly observes that Miss Madrigal paces her room, never closes her door, displays no pictures of loved ones and has all new clothes, with their tags still attached.

Laurel’s divorced mother Olivia (Elizabeth Sellars) has remarried, is pregnant and wants her daughter back. The grandmother has had custody for sometime and fights the suggestion when the mother arrives to see her child. Mrs. St. Maugham is put off when her daughter asks only about Laurel. “Ask about me, Olivia, ask about me!” she wails. Olivia says she will return later and her mother had better have Laurel ready to leave.

Laurel’s divorced mother Olivia (Elizabeth Sellars) has remarried, is pregnant and wants her daughter back. The grandmother has had custody for sometime and fights the suggestion when the mother arrives to see her child. Mrs. St. Maugham is put off when her daughter asks only about Laurel. “Ask about me, Olivia, ask about me!” she wails. Olivia says she will return later and her mother had better have Laurel ready to leave.

And as for Maitland, the fourth member of this household, Laurel has already whispered to Miss Madrigal that he killed his wife and child. In one of the film’s best scenes, Miss Madrigal, unable to sleep, goes to the library for a book and finds Maitland comfortably settled in a chair. He admits Laurel was partly right—he was at the wheel when his family died in a car accident. As Miss Madrigal is about to leave, he suggests she take a book, any book—for Laurel’s sake, as she must be sneaking about. “Laurel,” he says, “is not at her best through mahogany.”

While in the library, Miss Madrigal notices a collection of men’s photographs—some of Mrs. St. Maugham’s admirers, Maitland explains—and her expression darkens. To Maitland’s question that she might know one of them, she doesn’t reply, but takes the offered book and leaves. The photo front and center in the close-up is of Judge McWhirrey (Felix Alymer), who Maitland says is coming for lunch. McWhirrey, it turns out, will reveal a secret about Miss Madrigal which even Laurel didn’t uncover, nor could imagine.

Yes, sounds like typical soap opera melodrama, but what prevents The Chalk Garden from becoming overwhelmed by such stodginess is, first, the superb acting by all involved. In the London début of the Enid Bagnold play, Edith Evans was Mrs. St. Maugham, with Peggy Ashcroft as Miss Madrigal, directed by Sir John Gielgud. Second, the play is brilliantly transferred to the screen by John Michael Hayes, better known through his scripts for Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, The Trouble with Harry and the remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much.

Yes, sounds like typical soap opera melodrama, but what prevents The Chalk Garden from becoming overwhelmed by such stodginess is, first, the superb acting by all involved. In the London début of the Enid Bagnold play, Edith Evans was Mrs. St. Maugham, with Peggy Ashcroft as Miss Madrigal, directed by Sir John Gielgud. Second, the play is brilliantly transferred to the screen by John Michael Hayes, better known through his scripts for Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, The Trouble with Harry and the remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much.

A brief exchange between Mrs. St. Maugham and Maitland indicates the incisive, sometimes witty nature of much of the script:

“Now if you’ll excuse me,” the butler announces, “I’ll have to hurry to have lunch ready.”

“Hurry, Maitland, is the curse of civilization,” the woman gushes.

“The fact that I hurry, madame, gives certain people the leisure time to make such observations.”