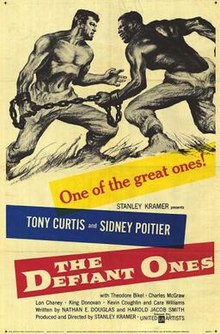

They couldn’t like each other less. They couldn’t need each other more.

Stanley Kramer was known as a crusading producer-director. Some of his earlier movies have hidden, sometimes not so hidden, messages. High Noon (1952), for example, had its own moral—on the surface a simple Western about a lone sheriff trying to recruit apathetic townspeople to join him in facing four vengeful outlaws; underneath, a more complicated allegory of the blacklisting of actors with supposed Communist connections, a scourge then terrifying Hollywood.

The messages in the five Kramer films that followed between 1958 and 1967 are perhaps less subtle and, in some cases, their preaching awkwardly cripples the movies. On the Beach (1959) warns of the suicidal dangers of nuclear war, Inherit the Wind (1960) pits religious literalism against scientific Darwinism, Judgment at Nuremberg (1961) reminds of the evils of Nazism, political collaboration and Holocaust denial and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) makes rather simplistic and idealistic interracial marriage.

Earlier than any of these five films is The Defiant Ones. The acting and photography (by Sam Leavitt) are so persuasive, the action so non-stop, the screenplay so tautly dramatic, that the underlying subject of racial prejudice can easily be forgotten, although its demoralization of character remains always near.

After a prisoner transport bus skids off the road in a rain storm, two convicts, a black (Sidney Poitier) and a white (Tony Curtiz), manage to escape and take off through a swamp. That they are chained together seems unlikely in the then Jim Crow South, where segregation applied everywhere, even in prison.

After a prisoner transport bus skids off the road in a rain storm, two convicts, a black (Sidney Poitier) and a white (Tony Curtiz), manage to escape and take off through a swamp. That they are chained together seems unlikely in the then Jim Crow South, where segregation applied everywhere, even in prison.

Each has his own grudge against society, his own resentments, his own cross to bear and, at least at first, his loathing of the other. Noah Cullen hates his life as a suppressed black and John “Joker” Jackson, with his own kind of suppression, resents his pre-prison life as a valet, who had to say “thank you” to the rich car owners whether they tipped him or not.

Through rain and mud and streams they run, Noah often seeming to better know the way. Their attempt to break the chain with a rock fails. They share their tales of oppression and humiliation, partake of the wild animals they kill, pass cigarettes between them and gradually, without saying so, come to respect one another, and before their journey together is over, to even like one another.

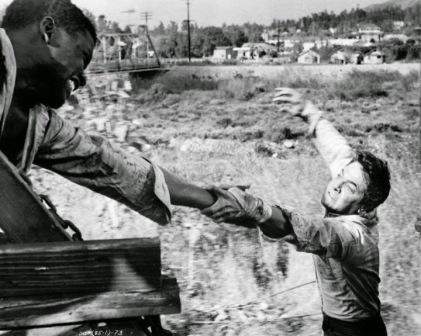

To elude an approaching truck, Noah and John jump into a deep hole. Finding it fourteen feet deep with a foot of water—it’s raining as well—they struggle to get out, John finally standing on Noah’s shoulders to reach the top. Still chained together, John reaches down to pull up Noah. (No doubles were used for the scene.)

To elude an approaching truck, Noah and John jump into a deep hole. Finding it fourteen feet deep with a foot of water—it’s raining as well—they struggle to get out, John finally standing on Noah’s shoulders to reach the top. Still chained together, John reaches down to pull up Noah. (No doubles were used for the scene.)

At a turpentine plant, they attempt to break into the company store for food but are caught and threatened with hanging until a worker (Lon Chaney, Jr.) puts the mob off, suggesting the two can be turned over to the police the next day. That night, the man confesses he was once a chain gang prisoner himself and frees them, receiving a promise that, if caught, they will not reveal how they escaped.

Next, they come upon a young boy (Kevin Coughlin) and his mother (Cara Williams). She takes them in and feeds them. They smash their chain and shackles. She makes a play for John, saying she wants to go with him in her car, but Noah prefers to take his chances on foot. She prepares him some food and tells him of a shortcut through the swamp.

Moments later, questioned by John as why she is so anxious to leave, she admits she didn’t give Noah a shortcut, only a way to bogs and quicksand, that she was afraid, if captured, he might betray John. “I’ve been waitin’ to get away from here,” she tells him—any way, with any one, it seems.

As John is leaving—he must warn Noah—the boy shoots him in the shoulder.

“Cullen! Cullen, where are you?” John calls over and over as he runs through the swamp, even stumbling into a muddy creek. In an abrupt cut, Noah is suddenly there.

At the sound of a whistle, the pair race to catch a passing train. Noah makes it aboard a flatcar and reaches down for John running alongside, their fleeting handclasp gives and John falls. Rather than leave his companion, Noah jumps off. After a few struggles through knee-high water, John slumps down. “I can’t make it,” he says.

At the sound of a whistle, the pair race to catch a passing train. Noah makes it aboard a flatcar and reaches down for John running alongside, their fleeting handclasp gives and John falls. Rather than leave his companion, Noah jumps off. After a few struggles through knee-high water, John slumps down. “I can’t make it,” he says.

The two stretch out, John resting against Noah’s chest, his head on his knee. Another cigarette miraculously appears and they pass it back and forth as the sheriff (Theodore Bikel), who has been chasing them since their escape, approaches, pistol drawn. “Cullen,” John says, “we gave ’em a helluva of a run for it, didn’t we?”

Since they were on the bus, Noah has been singing the same song, “Long Gone” by W.C. Handy and Chris Smith. Now it seems even more appropriate: “Sew so fast/Sew eleven stitches/In a little cat’s tail/Bowlin’ green/”. . . a pause from Noah, then more emphatic, with a twist of his head . . . “Sewin’ machine!”

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fBrw8dmgarM[/embedyt]