Here they are . . .

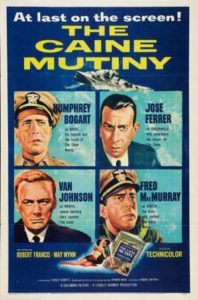

Lt. TOM KEEFER . . . the malcontent who laid the foundation for the mutiny.

Lt. STEVE MARYK . . . whose damning diary sparked the mutiny.

Navy lawyer Lt. BARNEY GREENWALD . . . who knew who should have been on trial.

Lt. Comdr. PHILIP FRANCIS QUEEG . . . who set his officers of edge.

A brand new graduate of Princeton’s midshipman’s school, Willis Seward Keith (Robert Francis), as fresh an ensign as the peach fuzz on his face, doesn’t know what he’s in for. It’s not enough, if he should stop to consider—maybe he has, though he is a bit naïve—that he’s the apple of both his possessive mother’s (Katherine Warren) eye and that of his vacillating girlfriend’s (May Wynn), which will cause conflict in his love life.

Now, on top of that, little suspecting what’s in store for him, he boards the destroyer-minesweeper U.S.S. Caine at the San Francisco dock, to become the junior among what appears to be a group of un-navy-like officers who tolerate a motley crew of dirty, half-dressed sailors. Arriving by launch, Keith climbs the ladder of the first ship his guide leads him. Looking about he says, “Sir, the Caine is a real beauty.” His guide corrects him: the Caine is the inboard ship. The two men cross the deck of this “beauty” and Keith sees for the first time his new home at sea, the near-derelict Caine, the T-shirted and even shirtless crew, with such telling nicknames as “Meatball” and “Horrible,” doing the morning wash.

The Caine Mutiny is from 1954, a year that included two other Best Picture nominations, the milestone On the Waterfront and the coming-out of Grace Kelly as a serious actress in The Country Girl. (The other two nominees, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers and Three Coins in the Fountain, were of lesser merit.) The Columbia film almost didn’t get made: the U.S. Navy at first objected to the portrayal of a mutiny, and sanctioned the movie only after it was prefaced with a card stating, and perhaps perpetuating the myth, that there has never been a mutiny on a U.S. Navy ship.

The movie took longer to film than expected—and cost more, too.

The movie took longer to film than expected—and cost more, too.

There was some opposition to Humphrey Bogart playing Queeg, primarily because he was far too old for the part in Herman Wouk’s acclaimed World War II novel. Richard Widmark was the first choice. Insisting on Bogart, producer Stanley Kramer, who had done so much to sustain Spencer Tracy’s career when he became an insurance risk, was also sympathetic to Fred MacMurray’s recent lost of his wife and provided a prominent, distracting role for him. Lee Marvin, a U.S. Marine Corps veteran of the war, acted as something of a technical advisor.

As for Ensign Keith’s new adventure that first day, before he climbs to the foretop of the Caine, the climax of his guided tour of the ship, Willie meets the seemingly blasé captain of the Caine, the shirtless Lt. Comdr. William DeVriess, a memorable introduction for Tom Tully. Willie also meets two other officers, executive officer Lt. Stephen Maryk (Van Johnson) and communications officer Lt. Thomas Keefer (MacMurray), who novel-writes in between his shipboard duties.

As for Ensign Keith’s new adventure that first day, before he climbs to the foretop of the Caine, the climax of his guided tour of the ship, Willie meets the seemingly blasé captain of the Caine, the shirtless Lt. Comdr. William DeVriess, a memorable introduction for Tom Tully. Willie also meets two other officers, executive officer Lt. Stephen Maryk (Van Johnson) and communications officer Lt. Thomas Keefer (MacMurray), who novel-writes in between his shipboard duties.

Though himself critical of the undisciplined captain and crew, Keith neglects to follow through on a dispatch requiring immediate attention. He tucks it in his pocket and forgets it, distracted, perhaps, by the day’s exercise, towing targets for battleship fire. Summoned to DeVriess’ cabin, he is criticized for his negligence and reads, in the captain’s newly finished fitness report on him, that he “may become a competent officer once he overcomes a careless approach to his duties.”

The information in the misplaced dispatch contains, Keith thinks, some good news: the sloppy DeVriess is being replaced. But the new commander, Phillip Francis Queeg (Bogart), although a by-the-book veteran of the Atlantic war, soon proves to be anything but mentally stable, rolling a pair of steel balls in his right hand when under stress.

The information in the misplaced dispatch contains, Keith thinks, some good news: the sloppy DeVriess is being replaced. But the new commander, Phillip Francis Queeg (Bogart), although a by-the-book veteran of the Atlantic war, soon proves to be anything but mentally stable, rolling a pair of steel balls in his right hand when under stress.

Queeg may order sailors to shave and tuck their shirts in their trousers, but Queeg himself is distracted in chewing out, at length, Keith and Keefer for a sailor’s (Claude Akins) improper appearance, while hushing the helmsman’s warning that the ship is turning back on its own towline, cutting the cable and setting the target adrift.

Later, while escorting U.S. Marine landing craft during an island assault, Queeg orders the Caine to drop a yellow dye marker and turns away instead of continuing to guide the boats. Afterward, the captain makes an ambiguous apology—“Even [my] dog,” he says, “doesn’t think I’m a monster.”—and asks for his officers’ co-operation and loyalty. Silence is their answer, and Keefer continues insisting to Maryk that Queeg is a paranoid personality.

When several servings of frozen strawberries disappear, Queeg instigates a major investigation, instructing his officers to conduct an all-night inquiry and strip-search all sailors for their keys, keys to be checked against the galley’s refrigerator padlock.

When several servings of frozen strawberries disappear, Queeg instigates a major investigation, instructing his officers to conduct an all-night inquiry and strip-search all sailors for their keys, keys to be checked against the galley’s refrigerator padlock.

Keefer now is even more insistent about Queeg’s paranoia and suggests Maryk read Article 184 of Navy Regulations regarding the relief from duty of an unfit commander. As Ensign Harding (Jerry Paris) is departing the ship on a compassionate leave, he tells his companions that the mess boys ate the strawberries and that the captain refused to believe him. It is now that Maryk begins a medical log on the captain’s strange behavior.

The final straw is Queeg’s behavior during a typhoon, giving delayed and incorrect orders, and finally freezing. Maryk relieves him as captain, with Keith and others on the bridge as witnesses.

The final straw is Queeg’s behavior during a typhoon, giving delayed and incorrect orders, and finally freezing. Maryk relieves him as captain, with Keith and others on the bridge as witnesses.

In San Francisco, lawyer Barney Greenwald (José Ferrer) cross-examines the officers of the Caine before Maryk’s court-martial for mutiny, accepting the case against his better judgment and seeing, perhaps, the person who should be on trial.

There are moments of levity during the trial, as there are throughout the film. When “Meatball” (Marvin) is asked if he liked Captain Queeg, he replies, “I liked him—not a lot, but I liked him.” When Harding replies to questions that none of the officers seemed scared during the typhoon and then is asked if any one was scared, he replies, “Just me. I was . . . I was plenty scared.”

It is only when Queeg is called to the stand that the trial turns in Greenwald’s favor: “Ahh, but the strawberries—that’s . . . that’s where I had them,” Queeg continues after a long invective against his many “incompetent” officers. “They laughed at me and made jokes, but I proved beyond the shadow of a doubt and with . . . geometric logic that a duplicate key to the wardroom icebox did exist—and I’d have produced that key if they hadn’t of pulled the Caine out of action. I—I—I know now they were only trying to protect some fellow officers . . . ” As he had become more restless, he produced from his pocket the pair of steel balls, so that, as his voice trailed off, their clicking was the only sound heard in the courtroom.

It is only when Queeg is called to the stand that the trial turns in Greenwald’s favor: “Ahh, but the strawberries—that’s . . . that’s where I had them,” Queeg continues after a long invective against his many “incompetent” officers. “They laughed at me and made jokes, but I proved beyond the shadow of a doubt and with . . . geometric logic that a duplicate key to the wardroom icebox did exist—and I’d have produced that key if they hadn’t of pulled the Caine out of action. I—I—I know now they were only trying to protect some fellow officers . . . ” As he had become more restless, he produced from his pocket the pair of steel balls, so that, as his voice trailed off, their clicking was the only sound heard in the courtroom.

Next scene, the officers of the Caine are celebrating Maryk’s “not guilty” verdict. Keefer is the last to appear, to thank Maryk for “not telling the fellers” about his denial on the stand of any complicity in the mutiny—as Greenwald would shortly say, “He had never even heard of Captain Queeg!”—and to say he didn’t have the courage not to appear at the gathering.

And then an intoxicated Greenwald arrives at the party. His extended speech, on its own, threatens to surpass even Queeg’s courtroom scene (and Ferrer’s overall performance is, indeed, admirable and mustn’t be overlooked). “When I was studying law,” Greenwald says, “and Mr. Keefer here was writing his stories and you, Willie, were tearing up the playing fields of dear old Princeton, who was standing guard over this fat, dumb, happy country of ours, eh? Not us. Oh, no, we knew you couldn’t make any money in the service. So who did the dirty work for us? Queeg did! And a lot of other guys—tough, sharp guys who didn’t crack up like Queeg.”

And then an intoxicated Greenwald arrives at the party. His extended speech, on its own, threatens to surpass even Queeg’s courtroom scene (and Ferrer’s overall performance is, indeed, admirable and mustn’t be overlooked). “When I was studying law,” Greenwald says, “and Mr. Keefer here was writing his stories and you, Willie, were tearing up the playing fields of dear old Princeton, who was standing guard over this fat, dumb, happy country of ours, eh? Not us. Oh, no, we knew you couldn’t make any money in the service. So who did the dirty work for us? Queeg did! And a lot of other guys—tough, sharp guys who didn’t crack up like Queeg.”

Greenwald confides that it would have harmed their case if it had been revealed that the officers had turned down Queeg’s request for help, that had they given him support, the mutiny would probably have been averted. “[Y]ou don’t work with a captain because you like the way he parts his hair,” he tells them. “You work with him because he’s got the job or you’re no good!”

Willie, having lost, perhaps, some of his naiveté, remarks, “ . . then we were guilty.”

Then Greenwald turns to the officer who always hated the Navy. “And now we come to the man who should’ve stood trial, the Caine’s favorite author, the Shakespeare whose testimony nearly sunk us all.” He lifts his wine glass. “Here’s to you, Mr. Keefer.” Greenwald throws the wine in his face. “If you wanna do anything about it, I’ll be outside.”

Everyone leaves until there is only Keefer standing alone.

When Keith reports to his new ship, he is surprised to find Captain DeVriess. Keith, apprehensive, looks at the frowning face, which slowly turns to a smile. “Take her out!” the captain says.

When Keith reports to his new ship, he is surprised to find Captain DeVriess. Keith, apprehensive, looks at the frowning face, which slowly turns to a smile. “Take her out!” the captain says.

Those familiar with The Caine Mutiny, the movie or the novel, will notice the omission from this synopsis of Willie’s relationship with his girl May. In the novel, both this romance and his activities as a naval officer are much expanded; in fact, the book ends with his efforts to finally marry her. In the film, the romantic aspect is handled less adeptly and, further, proves an intrusion, a distraction from the more important tension aboard the Caine.

It’s no help to either film or to the romance that the actress who plays Francis’ love interest is somewhat less than magnetic and prompts the question as to how she could have aroused a young ensign’s interest. Donna Lee Hickey adopted the name of her character in the film, and following its release was thereafter known as May Wynn. Playing a white girl captured by the Indians, she was in Francis’ next film, They Rode West, released a few months after the Wouk picture. Her last screen appearance would be in a TV episode of Shotgun Slade in 1960.

It’s no help to either film or to the romance that the actress who plays Francis’ love interest is somewhat less than magnetic and prompts the question as to how she could have aroused a young ensign’s interest. Donna Lee Hickey adopted the name of her character in the film, and following its release was thereafter known as May Wynn. Playing a white girl captured by the Indians, she was in Francis’ next film, They Rode West, released a few months after the Wouk picture. Her last screen appearance would be in a TV episode of Shotgun Slade in 1960.

The Caine Mutiny was Robert Francis’ remarkable film debut. Somewhat resembling, facially and physically, the good looks of Robert Wagner, who was born the same year, Francis had before him what appeared to be a promising career. He would make only three more films before his tragic death in a private plane accident in 1955 at the age of twenty-five. James Dean, whose death at about the same age, and also in 1955, would become the most famous example of the lost, disillusioned youth of his era. The parallels of promising actors dying young would be repeated yet again in 1972, when Brandon De Wilde, only thirty, would also die in an automobile accident.

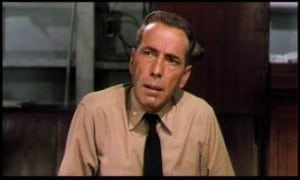

The ideal casting of Humphrey Bogart as Captain Queeg seemed preordained, as perfect a choice as other actors who are now forever associated with certain roles—Vivien Leigh as Scarlet O’Hara, Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes and George C. Scott as George S. Patton.

The ideal casting of Humphrey Bogart as Captain Queeg seemed preordained, as perfect a choice as other actors who are now forever associated with certain roles—Vivien Leigh as Scarlet O’Hara, Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes and George C. Scott as George S. Patton.

Stanley Kramer was reassured at every stage of the filming that he had made the right choice in Bogart, and his claim was reaffirmed, for one thing, at the end of Bogart’s trial speech when the cast and crew applauded him. And director Edward Dmytryk would say about him: “I don’t think there was ever a point . . . where he was reading the line for effect. Some actors have tricks in reading. Others, like Bogie and Tracy, never resorted to tricks. There was always a newness, and a freshness.”

Bogart, who had read Wouk’s great Pulitzer-winning novel, remarked, “I liked Captain Queeg. I felt I understood him.” Well that he might know him. Bogart himself possessed something of a dual personality, a gruff exterior hiding a sentimental core; a closed-mouth introvert on the set, who was an intellectual in private.

Bogart, who had read Wouk’s great Pulitzer-winning novel, remarked, “I liked Captain Queeg. I felt I understood him.” Well that he might know him. Bogart himself possessed something of a dual personality, a gruff exterior hiding a sentimental core; a closed-mouth introvert on the set, who was an intellectual in private.

Claude Akins, who played “Horrible” and who had been in the U.S. Army and had experienced chewing-outs by officers, could only praise how convincing Bogart was: “And I’ll tell you, Bogart scared the [crap] out of me. He was Queeg and he was pissed and he was letting me know it. You have so much to play with then when you get that from somebody. It just kindles you, ignites you and spurs you along.”

The intensity of Bogart’s Queeg helped him win the nomination as Best Actor of 1954; his only Oscar had come with The African Queen four years earlier.

The remaining major actors who play officers of the Caine maintain a high standard of their own. Van Johnson, convincing as the laid-back Maryk, comes into his own in perhaps his one dramatic, intense moment when he swears on the Bible that he will report Keefer if he persists in his accusations of Queeg’s possible paranoia. And Fred MacMurray, playing against his usual image of light leading man, is effective as the resident nasty, apart, of course, from Queeg. There is at least one earlier performance, in 1944, as Barbara Stanwyck’s accomplice in murder in Double Indemnity.

The remaining major actors who play officers of the Caine maintain a high standard of their own. Van Johnson, convincing as the laid-back Maryk, comes into his own in perhaps his one dramatic, intense moment when he swears on the Bible that he will report Keefer if he persists in his accusations of Queeg’s possible paranoia. And Fred MacMurray, playing against his usual image of light leading man, is effective as the resident nasty, apart, of course, from Queeg. There is at least one earlier performance, in 1944, as Barbara Stanwyck’s accomplice in murder in Double Indemnity.

Although not Oscar-nominated for Special Effects, The Caine Mutiny might well have been, if there had been more than three submissions; 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea won in 1954 for the squid fight. The Caine’s struggle in the typhoon—a ship model in a tank of wind machine-tossed water—is realistically executed, especially compared with the tackiness of much model use in seafaring movies. The U.S. Navy, which had been so against the picture in the beginning and would later make an about-face in providing generous access to Pearl Harbor, wasn’t about to risk a destroyer in a real storm, even if ideal filming could have been possible.

Max Steiner was nominated for Best Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture. Not an especially strong year in the category, he lost to Dimitri Tiomkin for The High and the Mighty. The confusing, ever-changing music classifications—in 1954, five nominations in three categories—would not be simplified, none too soon, until 1985 when only Song and Score would be the classifications.

Max Steiner was nominated for Best Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture. Not an especially strong year in the category, he lost to Dimitri Tiomkin for The High and the Mighty. The confusing, ever-changing music classifications—in 1954, five nominations in three categories—would not be simplified, none too soon, until 1985 when only Song and Score would be the classifications.

Steiner’s score is not especially strong, though the ever-present march is rather stirring, if repeated endlessly with little or no variation. Often heard are the U.S. Marine Hymn, and the song the crew of the Caine sing about Captain Queeg, “Yellow Stain Blues,” by Fred Karger and Wouk. May Wynn “sings”—it’s assumed her voice is dubbed—“I Can’t Believe That You’re in Love with Me,” a 1926 hit song by Jimmy McHugh and Clarence Gaskill, made popular by the likes of Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin.

All and all, The Caine Mutiny is a great war film, and like Patton, MacArthur and a few others, basically a drama with enough action thrown in to satisfy the criteria of the genre. In The Caine Mutiny, the study of a variety of characters, once on a page and now on the screen, is reinforced by an expert ensemble. Despite the actors’ different personalities, working methods and approaches to the art of acting, they come together as a whole, spurred on—sometimes driven—by a determined producer and a sometimes autocratic director.