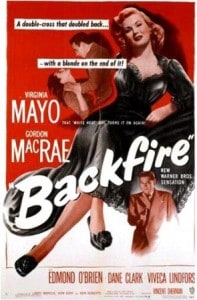

That “White Heat” girl turns it on again!

Directed in 1950 by veteran director Vincent Sherman, Backfire is fairly easy to describe if you can follow riddles wrapped in enigmas double bagged with confusion. Another example would be flashback in a flashback in a flashback.

Moviegoers of the time must have had the same confusion. Both posters and taglines for the film lean heavily on the success of the earlier 1949 film White Heat. It was a good marketing plan, as both feature Viriginia Mayo, Edmond O’Brien on the screen working through a script from Ivan Goff and Ben Roberts. There’s a fly in this ointment, however. Backfire was completed in 1948 and if anything the studio (Warner Brothers) knew it was a weak picture and hence shelved it. The great success of White Heat gave them the idea to capitalize further.

Virginia Mayo sadly is the one ‘A’ star in Backfire and her association with both pictures puts her squarely in the crosshairs. Neither the poster art depicting her as a femme fatale or the tagline which hints at the same are accurate. If anything, Mayo’s role (Julie Benson) in the film as nurse and love interest of Gordon MacRae (Bob Corey) is, with the exception of one important scene late in the film, an extremely minor one.

The film starts smartly enough, with Bob convalescing in a hospital through several surgeries. Julie is his nurse and of course they’ve become an item. While staying at the hospital Bob and fellow war veteran Steve Connolly (Edmond O’Brien) share dreams of their plans for buying a ranch together.

The film starts smartly enough, with Bob convalescing in a hospital through several surgeries. Julie is his nurse and of course they’ve become an item. While staying at the hospital Bob and fellow war veteran Steve Connolly (Edmond O’Brien) share dreams of their plans for buying a ranch together.

But as Bob’s release date nears, Steve disappears. A mysterious woman appears on night at the foot of his hospital bed (we find out later this is Lysa- played by Viveca Lindfors). She warns Bob that Steve is hurt and needs help.

Finally Bob is released but confronted by the police chief (Ed Begley) who is following up on leads that Steve is involved in a murder. This is the fairly strong and engaging first act.

From here the film deteriorates into a miasma of flashbacks, each one launched as the chief begins an interrogation of a new suspect. Though the flashback motif worked with great success in Citizen Kane and The Killers, among other films, here it simply confuses.

From here the film deteriorates into a miasma of flashbacks, each one launched as the chief begins an interrogation of a new suspect. Though the flashback motif worked with great success in Citizen Kane and The Killers, among other films, here it simply confuses.

At the end of these flashbacks, the few highly engaged viewers can piece together a murder mystery involving secret identities, fixed boxing matches, gambling, and call girls. But by the end of the film neither the viewers or the cast seem to really care and most are (like I was) simply happy that the journey is over.

In the hindsight of the over sixty years since the release of Backfire it is perhaps more than a bit unfair to be so critical of the film. It was intended, per Jack Warner, to be a ‘B’ film whose intent was only to get idle contract players to generate some revenue. Director Vincent Sherman thought (more or less correctly) that the script was weak and convoluted. Filmed immediately after 1948’s The Adventures of Don Juan, Backfire made had found Sherman wishing again for the alcoholic Flynn. Another holdover from Juan, Viveca Lindfors went on suspension briefly due to her concerns over the film as well. The larger ‘tell’ is that the studio held it for two years, waiting for the right time to capitalize with it.

Often incorrectly labeled as a noir film, Backfire is simply a murder plot with a few sparsely applied noir attributes. The strong first act gives the best sense of noir, with its overall blurred perception of reality through illness, surgery, drugs, and the like. From there any atmosphere dissipates with the breeze and it may as well be Perry Mason.

Often incorrectly labeled as a noir film, Backfire is simply a murder plot with a few sparsely applied noir attributes. The strong first act gives the best sense of noir, with its overall blurred perception of reality through illness, surgery, drugs, and the like. From there any atmosphere dissipates with the breeze and it may as well be Perry Mason.

I mentioned earlier that most of the cast seems exhausted and simply going through the paces by the end of the picture. One of the reasons may be that most of them are here only on spot duty- appearing for brief and sometimes random moments. Mayo has a bit part outside of one strong scene. Gordon MacRae, though present mostly throughout, seems perhaps out of his depth. His depiction of Bob is much like that of a passenger on a train- simply waiting for what he is going to see next.

Edmond O’Brien is the only one who drives any sense of urgency and passion on screen. In spite of the material, he is still engaged and gives a good performance. Dana Clark and Viveca Lindfors sadly fall more into the Mayo camp here, with nothing much to do either.

At the end of the day, Sherman was most likely correct in his assessment of the flaws of the film. They are mostly created by the script, which meanders from one flashback to another, tossing in coincidences along the way until all belief and logic is suspended. For what it is worth, all involved seem to have done the best with what they were presented. Director Sherman and cinematographer Carl Guthrie turn in a well shot and atmospheric film which includes several well paced action sequences. But the flaw remains tying everything together cohesively.

At the end of the day, Sherman was most likely correct in his assessment of the flaws of the film. They are mostly created by the script, which meanders from one flashback to another, tossing in coincidences along the way until all belief and logic is suspended. For what it is worth, all involved seem to have done the best with what they were presented. Director Sherman and cinematographer Carl Guthrie turn in a well shot and atmospheric film which includes several well paced action sequences. But the flaw remains tying everything together cohesively.

As movie critic for The New York Times Bosley Crowther wrote in 1950 “In this case, the title is descriptive of the effort expended by all. A short and sweet observation covers “Backfire”: It does!”

Even now it is hard to disagree with Crowther’s diagnosis. Perhaps this did need to gestate a bit before coming out. True too that some of the key elements were reformed in a more mature form in the much more successful White Heat.