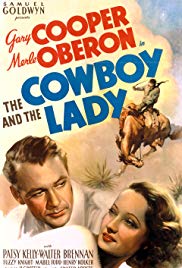

A blue-blood lady ropes a red-blood cowboy.

Even more so than many films, The Cowboy and the Lady was beset with more than its share of setbacks, changes, delays, misunderstandings, misrepresentations, broken promises and reluctant stars. For Gary Cooper, his previous two films had been flops, and this one would be no different, doing poor business at the box office. One of many, Cooper didn’t like the script, but was anxious to return to his cowboy image, albeit in a contemporary setting. He thought here he had a chance for a semi-comeback—not that he had ever really completely left.

His co-star, Merle Oberon, didn’t want to do the film and bribed producer Samuel Goldwyn with an elaborate smoking jacket to extricate herself, finally consenting only if she had a competent director, which turned out to be three directors.

The original director, William Wyler thought the script “awful, just awful,” and, according to one source, deliberately made even more than his usual famous retakes; according to another source, it was Goldwyn who wanted all the retakes, which, right away, doesn’t seem right from the money-conscious producer.

Anyway, Wyler was let go after three days. After the loss of Oberon’s prerequisite “good director,” Goldwyn now promised her a part for her current beau, David Niven, plus her pick of a new director. H. C. Potter, the choice, had almost finished the film when he was replaced by Stuart Heisler. And Niven’s scenes, although shot, were excised from the final print.

Some of the major plot ingredients of The Cowboy and the Lady immediately recall two far better films—It Happened One Night (1934), with Claudette Colbert and Clark Gable, and The Lady Eve (1941), with Barbara Stanwyck and Henry Fonda. In short, sophisticated—in some cases rich—ladies out and about in the world partnering up with men from a different life station than their own, and involving a certain amount of deception.

Some of the major plot ingredients of The Cowboy and the Lady immediately recall two far better films—It Happened One Night (1934), with Claudette Colbert and Clark Gable, and The Lady Eve (1941), with Barbara Stanwyck and Henry Fonda. In short, sophisticated—in some cases rich—ladies out and about in the world partnering up with men from a different life station than their own, and involving a certain amount of deception.

Like Colbert in her romp across the country, Mary Smith (Oberon)—no, that is correct: Mary Smith—lives a boring, routine life, overshadowed by the political life of her rich father (Henry Kolker). The life of the household, her uncle Hannibal (delightfully played by Harry Davenport), who acts crazy to entertain and deceive others, takes her to a casino for a change of pace.

When the place is raided by the police, her father sends Mary to the family mansion in Palm Beach. Her two maids (Patsy Kelly and Mabel Todd) take her with them on their blind dates. She meets a shy rodeo star Stretch Willoughby (Cooper) to whom she is immediately attracted. (While Oberon’s performance on their first meeting is a little over-played, as if she’s only pretending to like him, Cooper is at his best playing shy—perhaps, though, a little too coy—which he does so well in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936.)

Like Colbert, she pretends to be someone else, a maid struggling to support her father and sisters. The next day Stretch proposes, they are married by the captain on a voyage to Galveston(much as Stanwyck and Fonda are on a liner). The couple live for a while in Montana when Cooper is able to do some “cowboy things.”

Like Colbert, she pretends to be someone else, a maid struggling to support her father and sisters. The next day Stretch proposes, they are married by the captain on a voyage to Galveston(much as Stanwyck and Fonda are on a liner). The couple live for a while in Montana when Cooper is able to do some “cowboy things.”

Mary wants to tell Stretch she’s not a maid, but knowing how he feels about the idle rich, she tells him she has to return to Palm Beach for a while because of a family problem.

When she doesn’t return, he arrives at the Palm Beach mansion, only to find Mary in the midst of an elaborate dinner party whose guests ridicule his naive behavior. After it all, he says he feels like he needs a bath, then corrects himself: “On second thought, I think you’re the one who needs a bath,” and throws her in the family swimming pool. He storms out and makes plans to return to his ranch in Montana.

When he arrives, he finds the Smith family waiting. Mary’s father is anxious to know all about ranching, admitting that he has interfered in his daughter’s happiness. Uncle Hannibal raids the kitchen where Stretch’s mother (Emma Dunn) is baking a cake. In a comic moment routine, Stretch continues to untie her apron strings, she continuing to retie them. Mary and Stretch kiss in the kitchen and all is well.

When he arrives, he finds the Smith family waiting. Mary’s father is anxious to know all about ranching, admitting that he has interfered in his daughter’s happiness. Uncle Hannibal raids the kitchen where Stretch’s mother (Emma Dunn) is baking a cake. In a comic moment routine, Stretch continues to untie her apron strings, she continuing to retie them. Mary and Stretch kiss in the kitchen and all is well.

The following year came Merle Oberon’s signature movie, Wuthering Heights, to whose dramatic and critical level she would never reach again.

Beginning with Gary Cooper’s next film, Beau Geste (also 1939), there followed, in the next five years, a series of some of his best-remembered films—Meet John Doe, Sergeant York, Ball of Fire, The Pride of the Yankees and For Whom the Bell Tolls.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l7VpUlpGVX8[/embedyt]