“Who the hell wants to hear actors talk? ” H.M Warner, Warner Brothers, 1927.

If Cass Sperling could have chosen in advance which of the four Warner brothers she wanted for a grandfather, she could not have made a better choice than the man who filled that role in life. Harry seemed the straightest shooter of the group, the one with old-fashioned values and, perhaps, with the most integrity, and, since good people seem to suffer the most, the victim of another brother’s despicable betrayal. Sperling, as director and writer of this 2008 documentary, tells an interesting, well paced history of the brothers who believed that their films should “educate, entertain and enlighten.”

In the beginning of the documentary, Sperling asks people on the street to identify the Warner brothers. Most could not. But surely— Avid film buffs might not have heard of Albert or Sam, maybe not even of Harry, but surely they would have heard of Jack, who, as this history unfolds, emerges as the joker, the eccentric of the four. George Segal observes that Jack didn’t care what people thought, he just enjoyed being himself.

In the beginning of the documentary, Sperling asks people on the street to identify the Warner brothers. Most could not. But surely— Avid film buffs might not have heard of Albert or Sam, maybe not even of Harry, but surely they would have heard of Jack, who, as this history unfolds, emerges as the joker, the eccentric of the four. George Segal observes that Jack didn’t care what people thought, he just enjoyed being himself.

Jack’s less attractive deeds are surveyed—his naming names before the House Un-American Activities Committee and convincing brothers Harry and Albert to sell the studio, then buying back his controlling stocks and naming himself president. Smut is sometimes omitted, for example Harry Warner’s indictment, in the mid-’30s, of conspiring to violate the Sherman Antitrust Act by monopolizing theaters in St. Louis. There was a mistrial, the case never reopened.

In little over ninety minutes, the documentary—called a “film” on the DVD box, but there are no re-enactments (fortunately)—traces the lives of these four brothers, who began in obscure poverty with a rented store which they turned into a movie theater, showing over and over a worn copy of The Great Train Robbery. This, now, the first decade of the twentieth century. The chairs were borrowed from a local undertaker. In twenty years, their collective name, Warner Bros., became one of the master studios in the ’30s and ’40s and, though the brothers are long dead and the “studio” a shadow of its former self, the company is today part of one of the world’s largest conglomerates, Time Warner, Inc.

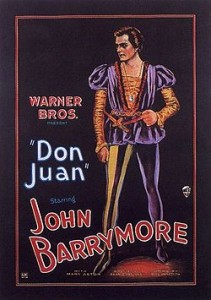

“Of All the Major Studios, One was Family” the DVD box boasts. Warner Bros. pioneered the Vitaphone process, sound on disc with John Barrymore’s 1926 Don Juan. Granted, all that was heard was the sound of clashing swords and Barrymore kissing the ladies. There was no dialogue. Sperling seems able to hit all the high points with competence and thoroughness.

“Of All the Major Studios, One was Family” the DVD box boasts. Warner Bros. pioneered the Vitaphone process, sound on disc with John Barrymore’s 1926 Don Juan. Granted, all that was heard was the sound of clashing swords and Barrymore kissing the ladies. There was no dialogue. Sperling seems able to hit all the high points with competence and thoroughness.

The next year, The Jazz Singer, largely silent but with Al Jolson singing a few songs, launched “talking pictures” and finished for good the silents. Because of Sam’s death at the age of forty—the first of the brothers to die—the other three were attending the funeral and could not savor the première. In 1928, Warner Bros. released Lights of New York, the first all-talking film.

With money rolling in, the studio moved from the Poverty Row section of Hollywood to Burbank, California, merging with First National Pictures. The company could join the big boys—Universal, M-G-M, Paramount, Fox and Columbia.

Warner Bros. was always known for giving the public what it wanted. Musicals, and many in color, lifted spirits during the Great Depression, but, against this escapism, there was the malice of the gangster films—Little Caesar, The Public Enemy, The Roaring Twenties—with their message of state and city corruption. Other films had a social conscience—Cabin in the Cotton, Bordertown, and I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, which prompted much-needed prison reform throughout the United States.

Warner Bros. was always known for giving the public what it wanted. Musicals, and many in color, lifted spirits during the Great Depression, but, against this escapism, there was the malice of the gangster films—Little Caesar, The Public Enemy, The Roaring Twenties—with their message of state and city corruption. Other films had a social conscience—Cabin in the Cotton, Bordertown, and I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, which prompted much-needed prison reform throughout the United States.

The biographical films were for culture and prestige—George Arliss in Disraeli and Voltaire; Paul Muni in The Life of Emile Zola, The Story of Louis Pasteur and Juarez; Edward G. Robinson in Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet and A Dispatch from Reuters. And even in some of these there was a message.

In justified detail, Sperling examines the brothers’ quick assessment of the Nazis. The studio was the first to cease film distribution in Germany, warning of the Nazi threat through Confessions of a Nazi Spy and Mission to Moscow. Even in a supposed swashbuckler, The Sea Hawk, King Philip II’s lust for world dominion substitutes for Hitler’s. Patriotic and pro-war propaganda emerged in Sergeant York, Yankee Doodle Dandy, You’re In the Army Now, Casablanca, This Is the Army, The Fighting 69th, Destination Tokyo, Edge of Darkness and so many, many other films. Warner Bros. was the “war studio.”

The studio did ’em all. There were also the melodramas of Bette Davis, the swashbucklers and Westerns of Errol Flynn and the comedies starring just about everyone on the roster at any given time—Joe E. Brown, Monty Woolley, William Powell and Joan Blondell, even stars better known outside of the comedy genre, such as Bette Davis, James Cagney and Olivia de Havilland.

No study of Warner Bros. would be complete without the famous cartoons—Porky Pig, Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Tweety Bird and a personal favorite, Foghorn Leghorn—cartoons that at one time were more profitable than Walt Disney’s.

No study of Warner Bros. would be complete without the famous cartoons—Porky Pig, Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Tweety Bird and a personal favorite, Foghorn Leghorn—cartoons that at one time were more profitable than Walt Disney’s.

After the crest of the wave and those glory days of the ’30s and ’40s, Warners persisted in groundbreaking movies, most obvious in stories that needed telling, some shockers for their time: A Streetcar Named Desire, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Bonnie and Clyde, East of Eden, Cool Hand Luke, Rebel Without a Cause, The Dark at the Top of the Stairs, Summer of ’42, The Exorcist, Blazing Saddles and Body Heat. Then, too, sometimes there were retreats to the tried and true, and the old-fashioned: My Fair Lady, Chariots of Fire and The Music Man.

The contributions of Flynn’s swashbucklers are conspicuously missing, including the milestone début of Captain Blood and what it meant for the studio financially, and as a star-maker and trendsetter. Ignoring the magnitude of its three-strip Technicolor photography, a clip from The Adventures of Robin Hood inexplicably appears, though the scene extracted is supposedly justified as social comment—Robin explaining to Lady Marian his good work for the poor and oppressed of England.

The contributions of Flynn’s swashbucklers are conspicuously missing, including the milestone début of Captain Blood and what it meant for the studio financially, and as a star-maker and trendsetter. Ignoring the magnitude of its three-strip Technicolor photography, a clip from The Adventures of Robin Hood inexplicably appears, though the scene extracted is supposedly justified as social comment—Robin explaining to Lady Marian his good work for the poor and oppressed of England.

Missing, too, is any detailed exploration of the stars who gave the brothers so much trouble—Cagney, de Havilland, Muni, George Raft, Davis and, agitator number one, Flynn. Only casually covered are Casablanca, the ultimate Hollywood movie, and The Maltese Falcon, perhaps the greatest detective movie ever made. But because The Brothers Warner is, after all, a biography and not a study of films or stars per se, the omissions are justified and the intent of the documentary totally successful.

Cass Warner Sperling (pictured) as the narrator requires a little getting used to—a professional such as Liev Schreiber, Linda Hunt, David McCullough or Stacy Keach would have added an extra professional touch—but before long she seems perfectly appropriate. And why not? Eleven years old when Harry died, she is often talking about her grandfather and his brothers, making for family intimacy. After all, the Warner Bros. studio was family.

Cass Warner Sperling (pictured) as the narrator requires a little getting used to—a professional such as Liev Schreiber, Linda Hunt, David McCullough or Stacy Keach would have added an extra professional touch—but before long she seems perfectly appropriate. And why not? Eleven years old when Harry died, she is often talking about her grandfather and his brothers, making for family intimacy. After all, the Warner Bros. studio was family.

.