WILD! That’s How He Lived! That’s How He Loved! That’s How He Fought!

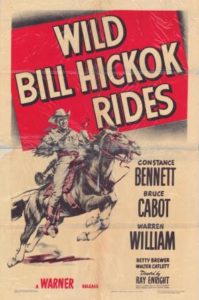

Though not in the class of a B picture, it is almost assured that no one came to the set to make 1942’s Wild Bill Hickok Rides with any delusions that they were making Gone with the Wind. What the resulting film lacks in character depth or plot development is made up for in action, with a city burning down, a flood, and a few good shootouts all crammed into a crisp 82 minute feature.

Constance Bennett gets top billing though in fact the picture continued a slow and gradual decline in her career which had begun a few years prior. Here she is a Chicago gambling house operator named Belle. Early on we also are introduced to Warren William playing Harry Farrel, who can simply be best labelled as a rascal with questionable business ethics.

As the film opens we are in Chicago during the Great Fire. Farrel and some of his cronies look down from far atop a nearby building, nonplussed as greater Chicago blazes. Calling them back inside from the spacious balcony, he makes his pitch. Some of the best cattle country he knows of is in Powder River, Wyoming and he aims to steal all the land for a bargain. Evidently somehow he knows that the current settlers of the area haven’t filed the appropriate claims on the land they live on.

As the film opens we are in Chicago during the Great Fire. Farrel and some of his cronies look down from far atop a nearby building, nonplussed as greater Chicago blazes. Calling them back inside from the spacious balcony, he makes his pitch. Some of the best cattle country he knows of is in Powder River, Wyoming and he aims to steal all the land for a bargain. Evidently somehow he knows that the current settlers of the area haven’t filed the appropriate claims on the land they live on.

Before heading west to Wyoming, he offers Belle the chance to partner with him in a new casino he plans to build in Powder River. With her Chicago establishment smoldering in the background and with nothing to lose, she accepts. What she doesn’t know (but we the audience have to assume) is that the casino is a cover for the land grab. Many of the finer points of the plot are lost in the shuffle and omitted entirely. While it isn’t difficult to piece together the little bit of character development present here, it can be a bit irritating and does show the overall slap-dash nature of the picture.

On the way to Powder River their train is held up, but a fellow passenger guns down the assailants. After a short discussion Farrel and Belle discover that the hero of the hour is none other than Wild Bill Hickok himself in the form of Bruce Cabot.

On the way to Powder River their train is held up, but a fellow passenger guns down the assailants. After a short discussion Farrel and Belle discover that the hero of the hour is none other than Wild Bill Hickok himself in the form of Bruce Cabot.

From this point on the picture is really Cabot’s, with Bennett playing a distant second fiddle. Warren William still has quite a few scenes, but he almost seems to be just there to observe the proceedings- or perhaps they just get away from him.

On arrival at Powder River, Belle soon discovers Farrel’s evil intentions with the landowners and abandons the casino with every intent of returning to Chicago to rebuild her life. Somehow along the way she’s managed to fall in love with Wild Bill. She warns him of the goings on as Farrel’s goons begin lining up to file official claims on the rancher’s lands.

Wild Bill in turn organizes the ranchers, who decide their only way to succeed is to combine all their respective herds and drive them to market for sale, with the resulting proceeds going to rescue their land. But now, Farrel in turn learns of the rancher’s efforts and send his men to blow the dam.

Wild Bill in turn organizes the ranchers, who decide their only way to succeed is to combine all their respective herds and drive them to market for sale, with the resulting proceeds going to rescue their land. But now, Farrel in turn learns of the rancher’s efforts and send his men to blow the dam.

Yes, there is a dam conveniently located just above the valley where the collected herd grazes. In a wonderful gunfight, Wild Bill and company gun down Farrel and his cohorts (including Ward Bond as the cooperative Sheriff), but not before the dam blows.

Surprisingly, the shots of the rushing water coming from the dam down into the valley don’t look much like the models they most certainly were. There is an especially good shot from above and in front of the the herd and a few riders as they race from the oncoming water. Only the respective size of the frothy wave shows how the show was done.

In yet another plot hole, it isn’t clear if the herd is saved or not. There are shots both of cattle running away (presumably to safety) and also swimming frantically (and presumably dying in the process). It seems of no consequence as Belle got her man and they share a stage back to Chicago.

In yet another plot hole, it isn’t clear if the herd is saved or not. There are shots both of cattle running away (presumably to safety) and also swimming frantically (and presumably dying in the process). It seems of no consequence as Belle got her man and they share a stage back to Chicago.

The final scene is of Wild Bill tossing Sylvester Twigg off the stage in disgust. There’s a running gag throughout the picture where Twigg- the town’s barber, newspaper reporter and (I think) banker- continually mouths off about besting Wild Bill in various feats of marksmanship and the like. Twigg’s balding and rather stumpy personality and physique add a bit of humor to his wondrous boasts.

Wild Bill Hickok rides isn’t an awful picture and does pretty much what it probably set out to do all those years ago, amuse young boys on a rainy afternoon. It is extremely fast paced and jumps from one action sequence to another, often with nary a plot point connecting them. But what do young boys need with plot anyway?

Wild Bill Hickok rides isn’t an awful picture and does pretty much what it probably set out to do all those years ago, amuse young boys on a rainy afternoon. It is extremely fast paced and jumps from one action sequence to another, often with nary a plot point connecting them. But what do young boys need with plot anyway?

The music- attributed to Howard Jackson- is suitably loud and stirring, but at all times seems a poor imitation of Steiner, with opulent scorings just one note off from popular songs such as “”Dixie” and “Turkey in the Straw” among others. It is meh as for overall originality but somehow it gets the job done.

Bennett and Cabot fare the best here, and both do fairly well with what they are given to work with. Cabot as Wild Bill gets the most important role, but Bennett perhaps gets the best line. When asked what she will do when she gets there, she replies, “Anybody I can.” It happens so fast that perhaps those young boys won’t catch it, but their fathers probably did. She also gets a song to sing, but sadly it isn’t that memorable.

Warren William seems to be the actor of the early 1930s for the time set in Chicago, full of his sparkling eyes and sly smirks. Once he gets to Wyoming though, his character (and William himself) loose all drive and motivation. It is almost an afterthought that he is gunned down by Wild Bill as he tries to ride off at the last moment. Though William made several more films, by this point (much like Constance Bennett in 1942) most of his feature roles were long past him and he had taken to character roles- albeit relatively strong ones.

Warren William seems to be the actor of the early 1930s for the time set in Chicago, full of his sparkling eyes and sly smirks. Once he gets to Wyoming though, his character (and William himself) loose all drive and motivation. It is almost an afterthought that he is gunned down by Wild Bill as he tries to ride off at the last moment. Though William made several more films, by this point (much like Constance Bennett in 1942) most of his feature roles were long past him and he had taken to character roles- albeit relatively strong ones.

Sadly, he perhaps here looks rather tired and worn, even for the actor Joan Blondell once characterized as “looking old even when he was young.” Sadder still, William would pass away only a few years after making Wild Bill Hickok Rides at the age of 53 in 1948.