“There are two people in this barracks who know I didn’t do it—me and the guy that did do it.” —— Sgt. J. J. Sefton (William Holden)

When it’s funny, it’s hilarious, and when it’s tragic, it’s terrifying. Which may reflect the extremes of war—when there’s no fighting, it’s boring, and when there is, it’s hell on earth. Clearly, Billy Wilder and his co-screenwriter were aware of this dichotomy when they scripted Stalag 17, based on a 1951 Broadway play that ran for almost five hundred performances.

Stalag 17 is the funniest possible war picture—or the darkest, however it is interpreted, or both, which seems the logical and obvious way to view it. Humor as an antidote to tragedy is as old as Shakespeare, as old as the Greeks, in fact. In the opening narration by one of the World War II inmates of a German POW camp somewhere along the Danube, Sgt. “Cookie” Cook (Gil Stratton) complains that stories about such prisoners never receive the attention, or the glamour, of submariners, frogmen or jungle guerrillas.

And here they are, over six hundred American airmen, all sergeants, in this one Nazi compound around Christmas of 1944, and because the Germans seem to know everything that goes on, a possible spy must reside among them. Thus Stalag 17, besides being a dark comedy, is also a mystery.

But who is the spy? Certainly not either of the two who are, in a sense, the comedians of Barracks Four, the camp jesters in this tale, Stanislaus “Animal” Kuzawa (Robert Strauss) and his straight man Harry Shapiro (Harvey Lembeck). There are some possible suspects, though: the barracks chief “Hoffy” Hoffman (Richard Erdman), the security man Price (Peter Graves), tough guy Duke (Neville Brand) and even “Cookie,” who seems above it all, the “chorus” in this Greek play.

But who is the spy? Certainly not either of the two who are, in a sense, the comedians of Barracks Four, the camp jesters in this tale, Stanislaus “Animal” Kuzawa (Robert Strauss) and his straight man Harry Shapiro (Harvey Lembeck). There are some possible suspects, though: the barracks chief “Hoffy” Hoffman (Richard Erdman), the security man Price (Peter Graves), tough guy Duke (Neville Brand) and even “Cookie,” who seems above it all, the “chorus” in this Greek play.

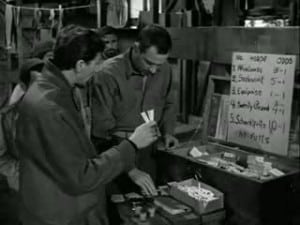

The general consensus is that the mole is J.J. Sefton ([intlink id=”285″ type=”category”]William Holden[/intlink]), the guy with the close-shaved head, the fast talker, ready with a dozen con games to swindle the men, the guy who looks out for himself, bribing the German guards for favors and blankets and fresh eggs and a lot more. The trunk full of cache proves his expertise.

In the opening scene of the film, the camera tracks through the middle of the barracks, bunks on either side, and past the table with a chessboard and, above it, a single dangling light bulb, to the cluster of airmen preparing for an escape. Sefton takes bets that the two men won’t make it out of the forest, just beyond the barbed wire fences. As it proves, the men are machine gunned by guards lying in wait, which automatically makes Sefton all the more a suspect.

He further infuriates the men by setting up a telescope of soldered tin cans and lenses bargained from the Germans. However angry at him, the men are their own victims and play along. For a peek at the Russian women prisoners being deloused—even if hidden behind the walls of their barracks—Sefton charges one cigarette or a half bar of chocolate. The line extends outside the barracks.

He further infuriates the men by setting up a telescope of soldered tin cans and lenses bargained from the Germans. However angry at him, the men are their own victims and play along. For a peek at the Russian women prisoners being deloused—even if hidden behind the walls of their barracks—Sefton charges one cigarette or a half bar of chocolate. The line extends outside the barracks.

For the mouse race, complete with arena and a name for each animal, he accepts bets calculated in cigarettes. And for a shot of schnapps from his distillery, it’s two cigarettes.

For the time being, though, Sefton’s roommates limit themselves to name-calling, threats and general snubbing, no violence—yet.

For the time being, though, Sefton’s roommates limit themselves to name-calling, threats and general snubbing, no violence—yet.

And life, if it can be called that, continues in Barracks Four. The monotony is broken by sailboat races at the cesspool, pinochle and chess championships, single-gender dancing to a contraband phonograph and listening to the BBC on a radio smuggled from barracks to barracks. Here again, just as the Germans knew about the tunnel and the stove that camouflaged its entrance, they somehow know about the radio and its chicken coop wire antenna and confiscate them.

Mail call is always a welcome diversion. Shapiro wants “Animal” to believe all his letters are from women, until his buddy discovers they are typed, in fact are numerous payment-due notices on his Plymouth and, with the last letter, as Shapiro says, “Now they want the Plymouth.” Shapiro delights in provoking the obsession “Animal” has for Betty Grable and his gloom when he learns she has married band leader Harry James.

Other humor is provided by one sergeant (Edmund Trzcinski) who reads from his wife a letter that begins, “You won’t believe it.” She has found on her doorstep a “most adorable baby” who looks just like him and has decided to keep it. “Why does she always say I won’t believe it?” he asks. “I believe it.” A long pause. “I believe it.” Later in the film, he is seen again holding the letter and saying, “I believe it.” Disguised as comedy, here is the anguish of men separated from their loved ones, the often recipients of those wartime “Dear John” letters. Trzcinski, along with Donald Bevan, wrote the original Broadway play.

And insanity, another liability of such incarceration, is exemplified by the speechless Joey (Robinson Stone) who plays his ocarina at the most inopportune times—during that opening escape attempt and later when the camp commandant, Colonel Oberst von Scherbach (Otto Preminger), addresses the Americans. Unfortunate, he says, that the compound is short two men, but at least his record of no escapes from Stalag 17 has been preserved.

And insanity, another liability of such incarceration, is exemplified by the speechless Joey (Robinson Stone) who plays his ocarina at the most inopportune times—during that opening escape attempt and later when the camp commandant, Colonel Oberst von Scherbach (Otto Preminger), addresses the Americans. Unfortunate, he says, that the compound is short two men, but at least his record of no escapes from Stalag 17 has been preserved.

For the inhabitants of Barracks Four, Sefton’s apparent fraternization with the enemy becomes intolerable when he bribes the guards for a day in the Russian women’s barracks. He has to be the stoolie. Upon his return that night, he is badly beaten, bruised about the face and nearly crippled. He warns his assailants that they will have to dish out another beating when they discover the real spy.

Through the camp grapevine, it is learned that a recently captured Lt. James Dunbar (Don Taylor), who had been bunking in the enlisted men’s barracks, is to be taken next day to Berlin for interrogation by the SS. (As pointed out in The Great Escape, it is fortunate that WWII Allied POWs in Germany were overseen by the Luftwaffe, not the brutal SS, though the uniforms in Stalag 17 show incorrect Luftwaffe attire.)

In a clandestine night scheme, the prisoners abduct Dunbar as he is being escorted to a waiting car for Berlin. His hiding place is known only to “Hoffy,” not even to security chief Price, who, it turns out, is the spy. Underdog and presumed traitor, Sefton trips up Price regarding the time of Pearl Harbor and pulls from the man’s pocket a black chess queen, one of an alternating pair, hollowed out to contain a message.

In a clandestine night scheme, the prisoners abduct Dunbar as he is being escorted to a waiting car for Berlin. His hiding place is known only to “Hoffy,” not even to security chief Price, who, it turns out, is the spy. Underdog and presumed traitor, Sefton trips up Price regarding the time of Pearl Harbor and pulls from the man’s pocket a black chess queen, one of an alternating pair, hollowed out to contain a message.